A Conversation with Barbara Kopple (DESERT ONE)

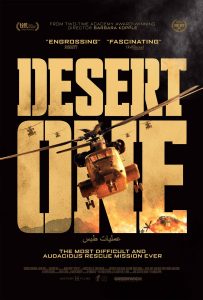

I recently spoke by phone with famed documentarian Barbara Kopple (Miss Sharon Jones!) about her new film, Desert One (which I also reviewed), which brings us back to 1980 and President Jimmy Carter’s failed attempt to free the Iranian-held U.S. hostages. Using a mix of archival material (including never-before-heard audio tapes), interviews (including one with Carter, himself) and animated recreations, Kopple tells the compelling story of all that went wrong, both with that attempt and with our foreign policy. Joining me in the conversation was my Fog of Truth podcast colleague Bart Weiss (of Dallas VideoFest). Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Bart Weiss: So, it’s been a long journey from Harlan County USA to Desert One. Could you talk about how the world of documentaries has changed since you started?

Barbara Kopple: At the very beginning, when I was starting, which was actually with a military film called Winter Soldier, with a collective of people – it was Vietnam veterans giving testimony of what they did in Vietnam – there was no support whatsoever. I mean, there were foundations and it just depended on what they wanted to fund. And now, documentaries are the rage. I mean, it’s incredible. People love them. They’re really searching for that sense of truth. There are budgets, Netflix, Amazon, HBO, A&…I mean, it’s just a wonderful time for documentarians and I had to struggle and suffer so much, not that I still don’t, to raise funds, but it was really, really difficult back then.

Hammer to Nail: And here you are now with a new film, Desert One. Why is the story of the Iran hostage crisis important today?

BK: Well, I just think that it’s history that people don’t know much about, and that it’s a story that really needed to be told. In a sense, it’s a story about heroism. It’s a reminder of the horrors of war and the roots of conflict between the US and the Iranian government, which still goes on. And it’s also about these guys who are heroes, who were willing to give up their lives and leave their families to save 52 Americans that were taken by the Iranian students and held at the American Embassy. And for me, it’s always so interesting to hear people’s stories. And these guys are so full of emotion. It’s sort of like the biggest thing that’s ever happened to them in their lives. And when they talk about it, many of them get choked up, and to see these big Delta Force guys, and Special Operations guys, and guys who were in Vietnam really letting you feel their emotions about this is something that was very important to me.

BW: Do you think Reagan’s team, or Reagan himself, negotiated with Iran, and do you see any parallels with foreign interference in our elections today?

BK: We will never know whether he did, but I did ask those questions to a couple of the men on the mission and they didn’t know for sure, but they guessed that probably this had been set up because a minute after Reagan was inaugurated, the hostages were let go, and it was just another humiliation for Jimmy Carter, because Jimmy Carter would not give up the Shah. And he also wanted to make sure that all 52 hostages were safe, and he did it with humanity, and he also tried to be very diplomatic and Khomenei would not hear any of that. He just said, “If you don’t give up the Shah, we’re not going to talk to you. We’re not going to negotiate with you. We’re not going to have anything to do with you. And you’re the devil.” And it was the destruction of Jimmy Carter and was a very tough thing for him for his campaign. And he lost, as we know, to Ronald Reagan, but he tried his best to do it in a different way. As well as things that are happening today, we’re all making those guesses that, yes, bad things are happening, that people are interfering in the elections, and we have a mad man in the white house.

HtN: I’m always interested in issues of access in documentaries, so I’m curious: did you need U.S. military approval for the project, and were they involved in any way?

BK: No, I did not need U.S. military consent, but I did for the Iranian part of it, because we did not go to Iran. We had an Iranian crew of women who were just wonderful. And one of the characters in the film they found when they were in a village and they were asking people if anybody had been part of the taking over of the American embassy and holding the Americans hostage. They didn’t find anyone, but they did find this 11-year-old boy who went on a bus trip together with his family every year, and that bus trip happened to be at just the same time and on just the same road as when and where Americans landed to start the mission. And so he and his family were taken hostage and he never would have thought he would have been a witness to this. But the wonderful thing about him is that he wanted to live so badly, which he did of course, so that he could go to his classmates and tell them about this unbelievable sight he saw of helicopters and C-130s and being held hostage in a bus at 11 years old, and it just made it so human because that’s something all of us would do, as well.

BW: That was a really great moment in the film, and it was a really good interview. And we’re really lucky that you were able to find that guy. So, as Chris is always interested in access, I’m always interested in the archival material. How did you get access to all that material of Jimmy Carter?

BK: Well, a lot of that material of him in the Oval Office and in other places came from the Carter Center. We were very lucky to be able to have access to a lot of that. And we had a person, who is in Atlanta, who went in all the time and scrubbed through things and sent us things. But being able to film Jimmy Carter was not that easy. It took me three months to be able to film with him. And they told me that I would have to call this one guy named Phillip Wise, at the Carter Center, to get permission. I also knew Bernie Aronson, who was Mondale’s speech writer, who put in a few phone calls to help me. And I also knew Jerry Rafshoon, who’s in the film, who led Jimmy Carter’s presidential campaign.

So, they put in a few words, but I would call Phillip Wise and his voicemail would say, “Howdy, this is Phillip Wise. And I’m not in right now.” And he would never call me back. So, I decided to have a relationship with his voicemail. And so I called every couple of days to give him an update of what we were filming and how important it was for us to get President Carter. And I just kept doing it, and finally he called me back and he said, “Howdy, Barbara, this is Phillip Wise.” And I said, “Oh yeah, I’d know your voice anywhere.” (laughs) And he said, “We decided we’re going to let you come film.” And I was able to go and film. He said, “You’re only getting 20 minutes.” I think I got 19 minutes and 47 seconds. So it was rough. I was nervous I wasn’t going to be able to film with him.

BW: And I think you probably used all 19 minutes and 40-something seconds in the movie. (laughs)

BK: Just about, yes. (laughs)

HtN: Did you have any other challenges for other kinds of archival material? Your film is so rich with it. And where did those audio tapes of General Jones and Jimmy Carter come from?

BK: Those came to us from some friends of ours who had them. And that’s sort of all I can say, but it’s the first time that they’ve ever been heard. And they’re so incredible, because the mission, as you know, was a secret mission. So there were no photographs, no footage, no nothing. So these audio tapes allowed you to feel history unfolding, or really sort of feeling as if you were with President Carter and Vice President Mondale and the generals going back and forth. And not that much was said, but you just got that feeling, that blow-by-blow feeling of what was happening.

And other challenges were that because the mission had no footage, we had to recreate it by using animation. And we had an Iranian animator who’s just incredible. And he lived in Iran for a while, but now he lives in Brooklyn. So he knew, understood the topography and he knew the story, and we worked really hard with our archival people, Eric Forman and David Cassidy, who would bring out all the history books and everything. And we’d look at the helicopters and the planes to make sure that everything was right, and really worked and listened to the stories that were being told to us by the men to make sure that we had everything right and were recreating the mission in the best way that we could. And one of the great compliments that came to us was when one of the guys said, “This is like it happened, it’s so close. We can’t believe it.” And it made some of them sad, and it made some of them very wistful about it, but that’s what we wanted to do. And they said they liked it, that it was true, that it was real.

BW: So one of the things young filmmakers can take out of this is that you have to have good friends who have secret stuff and be persistent.

BK: Well, you have to have a sense of perseverance whenever you’re making films. Just keep on it and to keep doing it, no matter what obstacles are put in your way.

BW: Absolutely. So, back to the interview with Carter, which was incredibly compelling. Thank you for the persistence, because hearing him and looking at him as he’s talking is very powerful because it is in a sense so much about what he did and how everybody else reacted in their heroism. But he’s so central to the role of this, and to hear him talk about it gives the film so much more resonance.

BK: One of the things that moved me so much, as I was asking him about his feelings about all of this and about what happened in the mission with eight men dying was that he said that he was heartbroken. And he said that his father died when he was a young man and he never thought that he would feel those feelings again. But when he heard about these men, everything came rushing back; it was the same kind of feelings that he had when his father had died. And that just gave me chills and really moved me.

BW: Carter has spent all his life working for human rights, and the Shah of Iran, let’s just say, was not a great supporter of human rights. In fact, quite the opposite.

BK: Exactly.

BW: So, why didn’t he just say, “You don’t deserve the protection of the United States”? If he would just have turned him over, none of this would have happened. Did he ever talk about that?

BK: He didn’t talk about that at all, but what I heard about it is that the Shah was such a good ally to so many presidents and the Shah was dying of cancer and needed medical help, and other countries would not let him in. And we did, because I guess Jimmy Carter was following suit of all the other presidents. I think that he felt that was the humanitarian thing to do.

HtN: How have you seen the role of women in documentaries change over the years? And do you think it’s been different in documentary than it has been in narrative cinema?

BK: I think women have always done a lot in the documentary world because it was a struggle, there wasn’t much of a budget, and it takes years to make them. And in narrative films, I think women are finally really breaking in now, but I think we’ve always done documentaries. It hasn’t changed that much. I mean, there are many more of us now doing it, but that was always a more open path for women than narratives.

HtN: Indeed. There have been some amazing women documentarians, you among them.

BW: Thank you for this opportunity, Barbara. This was really wonderful. It’s great to talk to a living legend.

BK: Aww. Thank you!

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)