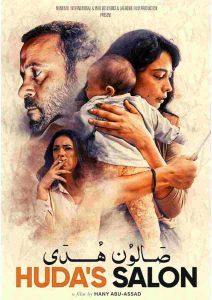

A Conversation with Hany Abu-Assad (HUDA’S SALON)

Writer/director Hany Abu-Assad (The Mountain Between Us) has a new film out, Huda’s Salon (which I also reviewed), in which he explores the challenges of life in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. In particular, his focus is on how women cope within a deeply patriarchal society, their loyalty pledged to men who offer them very little in return. Still, is it better to seek escape at the hands of Israeli authorities, or is that an unconscionable act? It’s a complex movie, filled with nuance and strong performances. I just had a chance to chat with Abu-Assad, via Zoom, ahead of the film’s March 4 release. What follows is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity. In addition, I have tweaked a few idioms here and there to better reflect American English, without changing the essential meaning of Abu-Assad’s words.

Hammer to Nail: What is the inspiration for this story that, as an opening title card informs us, is “based on true events?”

Hany Abu-Assad: I read an article 20 years ago about a salon that was used by the Israeli Secret Service to recruit girls by drugging them and filming them naked in the company of a man and then blackmailing them. And that shocked me, because your image of a salon is that it has hairstyling and is a very nice place. And I said to myself that, one day, I should use that for a movie, but I didn’t have the story for it. Then, about 2 years ago, my wife said that she wanted to write a story about strong women in Palestine and I told her about this article. And she said, “OK, it’s an article, but what’s the story?” And I didn’t know and I went to sleep. But the next morning, I came up with the outline of Huda’s Salon.

And she said, “My God, this is just like you, because your stories are always told in the thriller genre.” Because this article, you could have taken it in any direction you wanted; you could make a family drama, an artistic avant-garde experience, but I put it in an intense thriller. And I love this genre because it intensifies the experience of the audience as it relates to the theme and everything. And I have studied this genre very much. My biggest influence is probably Hitchcock, for sure, but also masters like Melville, the French director, and also the Egyptian director Kamal Hussein. And thrillers are often just entertainment, with no philosophy behind them, but I always try to use this genre to explore complex themes in a simple way.

HtN: I think that’s often the best thing one can do with genre filmmaking, right? To take the conventions of the genre and use them to explore larger issues. So, in the press notes for the movie, you quote Mike Nichols saying that “there are only three kinds of scenes: a fight, a seduction or a negotiation.” How does that apply to Huda’s Salon?

HA-A: (laughs) So, I knew this quote and I went to my actors…because actors want direction, you know?… and I said, “Listen, this is what Nichols once said, and I want you to try to make every scene those three things in one. Try to make the same scene a fight, a seduction and also a negotiation.” And the actors loved it! (laughs) For them, this was so good.

HtN: Speaking of your actors, you’ve obviously worked with Ali Suliman, who plays Hasan, before, starting with the 2005 Paradise Now. And I understand that the woman playing Huda, Manal Awad, is very well-known, but as a comedic actress, mostly. How did you go about casting your main parts, including Maisa Abd Elhadi, who plays Reem?

HA-A: When I wrote the outline, before I wrote the script, I realized that I wanted to know who would play the parts. I knew that we would need a very strong actress who would dare to be emotionally naked and also physically naked. Maisa was the only one I knew who would do it, who is brave enough to do it, and she is a great actress. I called her and told her, “I won’t do the movie if you … I won’t write it, even … if you are not in it.” And she had to think about it. It was not easy for her to do this role. It was very brave of her. She called me back two weeks later and said, “You know, Hany, I struggle with this, but I will do it.” And after that I needed to find Hasan and Huda.

Manal Awad, as you said, is very well-known, and she’s a huge star, but yes, as a comedic actress. She’s also a theater actress and has done Shakespeare, Brecht, and more. But nobody knows her from her theater work. And because I wanted to shock the audience from the very first scene, I realized that if I would take Manal and people were expecting a fun movie, given her presence, and suddenly she turns out to be a monster, the shock would be double, actually. So, I called her and said, “This is my plan. I want to make you a villain.” (laughs) And she said, “Oh, my God! I’m so beloved here!” And then she thought about it and said, “It’s a great challenge. Let’s do it!”

Then I called Ali Suliman. I was the first director he worked with and since then he has become a relatively big star in the world, or at least well-known. And I said to him, “It’s time now to have a reunion and see what we can do together and make of Hasan a very ambiguous character.” And I believe that Ali is an actor who can flip in a second, from good to bad. Not a lot of actors can do that. And Ali can change in a second, which is really good for the role of Hasan. Sometimes he’s trying to be nice but then suddenly shifts and becomes evil.

And so when I got the three of them to agree to do the film, then I started to write it. And they helped me in shaping the characters. Not just during the writing, but also during the shoot.

HtN: Well, it’s a very complex story and I really appreciate the way you approach multiple sides to every issue. Your ideological perspective is not monolithic. How is the film being received back home or, if it has yet to screen there, how do you think it will be received?

HA-A: So far it has only been playing at festivals. But Arab women are the ones who will most understand this story, because they understand exactly how vulnerable they are in a society where some of the men are misogynistic and will prefer to punish the victim rather than to lose their authority. Because in this kind of situation, they cannot punish the real perpetrators; they have no authority over the occupiers, but they still have authority over the victim. They prefer to punish the victim and keep their authority.

So, although not all men in Palestine are misogynists, in general the women will understand this kind of situation more than men. And it was shown at a festival in Saudi Arabia and when the lights came up, I watched the faces of the women in the audience and saw the horror of what they had experienced. And some of them were crying. So I felt as if I had captured the experience from a woman’s point of view.

HtN: And certainly your ending doesn’t resolve anything, so I can imagine how women who may empathize with Reem would be left in a certain kind of tragic place. How did COVID-19 affect the production. I understand you had to shut down for 7 months. Is that right?

HA-A: Yes. You know, it was a nightmare, I have to say, although there is a good side to it, because when you shut down for so long you have more time to write your story. And in some ways, I really made it a better script. But during the shoot I had the constant fear that somebody would get sick and I would feel responsible. And at that time, no company would insure us from COVID or the consequence of COVID. So many times I made compromises and decided not to do things as I had originally planned, hoping to maybe fix it in the editing room. And I therefore felt, while editing, that I did not have a lot of options to explore. So, that was a negative effect. But the rewriting of the script over those 7 months was a positive.

HtN: You have many long takes in the movie, particularly in that opening scene where, yes, you do shock us because Huda suddenly reveals herself to be something we didn’t think she was. How did you devise that aesthetic for this particular movie?

HA-A: The reason why it is one shot is because I realized I wanted to make a movie where the audience is stuck in time and place. Editing makes the movie digestible: you can accept the passage of time easily. With a single take, you have to wait while they move from one room to the other and you are stuck with them. This intensifies the experience of Reem being drugged and effectively raped … for her, it is like being raped.

And in the same sense, I wanted to explore the cinematic contradiction between the objective and subjective points of view. When you are stuck in time and place, you are a witness and you are not subjective, as an audience. And I wanted to explore a way to make even this objective point of view a subjective one. So I played with the camera movement in a way that when I wanted it to become subjective, the camera became a mirror for the character, coming closer to her, and what she sees, we see. But meanwhile, you are still stuck there in the objective position, as somebody who cannot be manipulated, stuck there in time and place.

So this was the approach and I’m very pleased with this experience because it gave me an opportunity to explore another side of me than the normal, invisible style of filmmaking I usually employ. All my movies are shot in this, what I call, “invisible” style, where the camera doesn’t draw attention to itself. There is a style, but it is serving the story, but now the style becomes part of the story.

HtN: I think it worked and I found it quite interesting. Thanks for chatting with me, Hany! I wish you all good things with the film.

HA-A: Thank you, Chris.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)

IFC Films; Hany Abu-Assad; Huda’s Salon movie review; Hany Abu-Assad interview