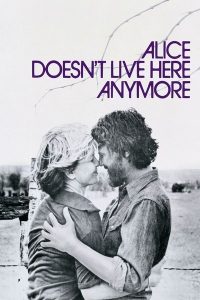

ON THE FRINGE, PART THREE: ALICE DOESN’T LIVE HERE ANYMORE (1974)

Something was happening in the American cinema starting in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s.

Something was happening in the American cinema starting in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s.

Among other progressions in societal mores, technology and legalities, this decade+ could arguably be considered a Golden Age of courageous truth-telling films that mine subject matter from the highest pinnacles of our society, straight down to the lowest “on the fringe” subcultures.

Less questionably, there was a noticeable trend of earnest, unvarnished filmmaking taking hold across the international arena, ignited by the catalytic postwar works of the Italian-Neorealists and French New Wave.

The New German Cinema blossomed with impassioned, stripped-down films of wunderkinds Wim Wenders, Volker Schlöndorff, Werner Herzog and – quite possibly the greatest filmmaker of all time – Rainer Werner Fassbinder.

Fellow Europeans such as Ingmar Bergman dove in deep with his epochal take on the circadian, joyful, often brutal vicissitudes of modern domesticity with such works as 1973’s Scenes From a Marriage. Before exploding onto the American scene in the eighties, Dutch filmmaker Paul Verhoeven was prolific in his string of no-holds-barred projects, exemplified by his Turkish Delight (also released in 1973). The picture would go on to become the most commercially successful Dutch film of all time and was hailed “the Best Dutch Film of the Century” by the Netherlands Film Festival as recently as 1999.

Though it took place in an earlier (if not analogous) era, Spanish director Victor Erice produced (yup, in 1973) his mesmeric, time-protracting fable of the small villager life, The Spirit of the Beehive (which, to some viewers/critics, appears to be as much an inspiration for Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth as was Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s Delicatessen for del Toro’s The Shape of Water).

This uber-naturalistic approach was again employed in the production of Jamaica’s The Harder They Come (though originally released in 1972, it’s worth noting the synchronicity here of the film’s having been first shown in America in – you guessed it – 1973). Harder was later credited as having substantial influence on cultural development the world over, including the mainstream’s introduction to reggae.

Chilean Alejandro Jodorowsky wildly jettisoned beyond previous-imagined limits of low-budget creativity (in both production and release strategy) with 1970’s genre-defying El Topo, while Japan’s Nagisa Ôshima pushed even further in the blasting of conventional sexual taboos with 1976’s intimate period drama In The Realm of the Senses.

1975’s controversial Senegalese film Xala, meanwhile, ends with a memorable scene of denizens of the lower-class quite literally (and disgustingly, in brutal close-up shots) taking turns spitting gobs of phlegm on the film’s anti-protagonist member of the upper-class elite.

Ken Loach was just kicking off his own decades-worth of naturalistic films with 1967’s Golden Globe-nominated Poor Cow in Wales. Irreverent Czech filmmaker Milos Forman’s Loves of a Blonde and The Fireman’s Ball would have affinity with fellow Czech New Waver Jirí Menzel’s Closely Watched Trains. While Sweden’s Vilgot Sjöman’s extreme provocations I Am Curious (Yellow) and (Blue) were so realistic in their depictions of story and characters that actress Lena Nyman was, in real life, despised by many of her fellow countrymen for her deft (but fictional) portrayal of a fearlessly bratty rebel (who happened to have her same name).

A likeminded series of provocations would be unleashed by Yugoslavia’s Dusan Makavejev, whose own mischievous, rambunctious melding of documentary and narrative filmmaking can best be seen in his Sweet Movie and WR: Mysteries of the Organism.

Youthful Frenchwoman Chantal Akerman joined the enfant terrible clique of New Wavers Agnès Varda, François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard with her radically meditative Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels of 1975, lauded by the New York Times as the“first masterpieceof the feminine in the history of the cinema.”

Indeed, it could be said that this barrier-annihilating period of cinema throughout the world so aligned (and allied) with the awesome output of filmmakers in the US was perfectly capped in 1980 by comrade French New Waver Louis Malle, whose English-language American film Atlantic City grants the gravest sense of where the American Dream can too often lead for mice and men with best laid plans.

(The same could potentially be said about another foreigner, Herzog, whose 1977 depiction of a ragtag coterie of German immigrants in trailer park America, Stroszek, is nearly peerless in its encapsulation of the wonderfully nuanced American experience for so many – immigrants or otherwise – at the time.)

It was here in the US that – while indie master John Cassavetes continued to labor away with 1970’s Husbands, 1971’s Minnie & Moskowitz and (arguably) his magnum opus, 1974’s A Woman Under the Influence – “rock star” filmmakers broke out with a wild spate of projects dealing with the genuine experience of ordinary people or, failing that, the ordinary experience of extraordinary people in exceptional situations.

It was the era of Hal Ashby (who has finally received his due in contemporary times via the forthcoming, star-studded documentary Hal), whose impressive run of uncompromising films focused intensely on the day-to-day, earnest minutiae of American life in a movie released almost every year throughout the seventies. Exhibit modern classics: Being There, The Last Detail, The Landlord, Shampoo, Harold & Maude and Coming Home. The latter of which features actual “wounded warriors” home from Vietnam and a glass-ceiling-shattering scene involving one of cinema’s first-ever portrayals of lovemaking involving a person with a disability.

This was the time of Robert Altman, Arthur Penn, George Roy Hill, Francis Ford Coppola, Herbert Ross, Woody Allen, Martin Ritt, Peter Bogdanovich, Sidney Lumet, Mike Nichols, Sydney Pollack, Bob Fosse, John Schlesinger, Roman Polanski, Stanley Kubrick, Brian De Palma, William Friedkin, Elaine May and Bob Rafelson. It was the time of Fat City, Midnight Cowboy, Five Easy Pieces, Norma Rae, The Swimmer, Melvin and Howard, Kramer vs. Kramer, Nashville, Network and Norman Mailer’s own maddening fusion of documentary and narrative filmmaking with such paeans to the era’s sense of anarchy and chaos as 1970’s Maidstone.

No matter if outputting period pieces such as Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid; Bonnie and Clyde, Paper Moon, The Last Picture Show or They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?; musicals such as All That Jazz; heist movies such as Dog Day Afternoon or even animated films via nearly every picture by Ralph Bakshi, filmmakers of this time were uncannily, unabashedly true-to-life in their storytelling. Perhaps across the board and more often than any other time in film’s short-lived history.

Yes, even more outlandish genres previously consigned to the realm of the fantastical were becoming that much more human in scope. Consider the horror genre, consistently inundated at this time with works that dealt with the true and real. Take such landmark pictures as John Carpenter’s Halloween, Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left and the example par excellence, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. No longer was the fear that of ghosts, goblins, vampires and demons onscreen; now audiences were being terrified by the REAL: psychopaths and murderers who could very well live right next door. Or, in the case of 1972’s The Stepford Wives (portending Get Out), the terror could stem from one’s trusted mate.

The very means of filmmaking themselves became far more egalitarian and accessible to a slew of new filmmakers bursting through the previously gilded gates: Melvin Van Peebles, John Waters, Herschell Gordon Lewis, Russ Meyer, Roger Corman, Robert Downey Sr., the Kuchar Brothers, Gordon Parks, Jr., just to name a few. It was through such means that entirely new elements of American society were being at long last showcased to larger audiences.

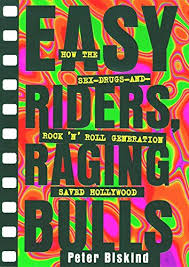

As illuminated in Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls and mega-producer Robert Evans’ memoir (brilliantly adapted to documentary feature) The Kid Stays in the Picture, 1969’s pointed middle finger to the so-called “Establishment,” Easy Rider, proved there was both critical and commercial viability in these red-hot fusillade of exhilaratingly fresh projects.

As illuminated in Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls and mega-producer Robert Evans’ memoir (brilliantly adapted to documentary feature) The Kid Stays in the Picture, 1969’s pointed middle finger to the so-called “Establishment,” Easy Rider, proved there was both critical and commercial viability in these red-hot fusillade of exhilaratingly fresh projects.

From there, we arrived at a time that was likely the closest American cinema has ever gotten to an “anything goes” methodology where studio heads, moneymen, producers, filmmakers, actors and writers alike were ready to make what had previously been forbidden or ignored available to the general public.

It’s no wonder it was during this time that we witnessed the rise – and in some ways, mainstreaming – of the porn industry, with such integral pictures as Deep Throat and Behind the Green Door (both released in 1972).

Right smack-dab in the middle of this remarkable period of American cinema comes a young Martin Scorsese, straight off the heels of his Steinbeckian tribute to yesteryear train tramps, Boxcar Bertha, and his career-making scrutiny of his own trenches of New York City (aptly, simply titled Mean Streets).

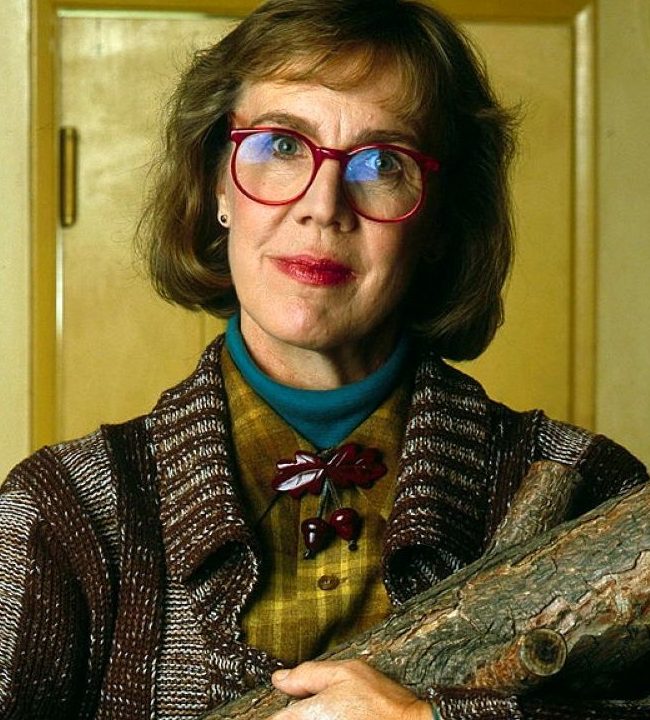

Tallying forth into the fray with 1974’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, Scorsese serves up a delectable smorgasbord of superstars on the rise: Ellen Burstyn; Kris Kristofferson; a pre-Taxi Driver upstart Harvey Keitel; perfectly cast Jodie Foster, who nearly steals the show in every scene she’s in as the hearty girlfriend of Alice’s young son, Tommy; and a hilarious, endearingly serpent-tongued Diane Ladd.

Scorsese flexes his incipient filmmaking muscles with a picture that, though certainly not flawless, is as pure a portrait of the down-to-earth American experience of the time as any of the many to be released in the late sixties and seventies.

As one of the original generation of “film student filmmakers” (along with Coppola, Steven Spielberg, George Lucas and John Milius), Scorsese ambitiously amps up the start of Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore with a flashback in the thirty-five year-old mother’s life to when she was a young hotheaded adolescent. It’s an explicit allusion to the great works of traditional cinema – the colors, scope and cinematography evoking the likes of Gone With the Wind and The Wizard of Oz.

Scorsese then puts what will be his own irrepressible stamp on the scene by having the young Alice fire off a series of irreverent statements – “They can blow it out their ass” – and abruptly shifts to the mid-seventies world the rest of the film takes place in with not a lush orchestral score but, rather, soundtrack by proto-punkers Mott the Hoople, signaling to audiences (and fellow filmmakers alike), that this story is taking us right into that new era of which he would be one of the driving forces.

It was 1974, after all: Flower Power had all but wilted, the punk scene had only just begun grinding out (based largely in Scorsese’s own “mean streets” New York City), and Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, under Scorsese’s masterful stewardship and his phenomenal cast’s auspices, would tell the crucial story of the modern, single, widowed mother out there on the road with her adorably obstreperous kid figuring out his own way in a culture that had yet to pay mind to his generation at all.

“How did I get such a smartass kid?” Alice asks, with the quick riposte from her precocious son: “You got pregnant.”

It’s one of many funny but genuine moments between a young mother and her son that hollers out of Burstyn’s Academy Award-winning performance played against Tommy, portrayed by newcomer Alfred Lutter (who would go on to be a major feature of The Bad News Bears films, as well as reprise his role as Tommy in the television pilot based on the film, Alice, before being replaced for the actual series run).

Scorsese proves to be one of the real stars of the film, supervising behind the camera and editing bay, trying out further stylistic flourishes that would become his signature – the dynamic camera movements and alternations between aspect ratios and varied editing techniques that incorporate hypnotic long shots of the road on which Alice and Tommy traverse, to rapid-fire Eisensteinian cutting a decade before MTV would make the style a household concept across the globe.

These techniques allow Scorsese to gracefully vacillate between subjective and objective perspectives without disrupting the verisimilitude of the scenes. It is this masterful control that would lead to Scorsese’s style becoming so well regarded in years to come for being implemented in such works as Taxi Driver, Goodfellas, Casino and The Wolf of Wall Street.

Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore’s deceptively simple plot fires up after Alice’s indifferent-at-best/abusive-at-worse husband dies in a horrible car accident. All at once, this housewife nursing a secret passion for singing must find her way in the world with a son in tow to whom she muses she just spent her last $2000 on the funeral.

“What are you gonna do, Mom?” Tommy asks.

“What are you gonna do, pal?” she answers. “We’re in this together!”

Alice and son hit the wide road out toward her hometown of Monterey, California, where things seemed so much happier (hence the majestic colors and cinematography of the film’s starting flashback; it’s the near-mystical dream toward which Alice and Tommy aspire reaching).

They stop in various small southwest towns where Alice does her best to find work singing at bars and trying to stay out of trouble with the men folk she meets along the way. Tommy remains in the cheap motels they can barely afford, bored out of his mind and worrying about whether they’ll make it to Monterey in time for his birthday … and his starting of the new schoolyear.

Alice resigns herself to working at a greasy spoon diner prototypically named Mel and Ruby’s – a raucous, harried affair that sends most first-day servers fleeing in tears, according to Ladd’s bee-hived head waitress Flo (who soon suggests Alice unbutton her top button to get more tips).

The dream of making it to Monterey is again delayed in part when Alice meets Kristofferson’s cavalier rancher, David, who woos her (and, cleverly, Tommy) before Alice realizes there may very well be something worth staying in Tucson for, after all. Tommy, having met and gotten wine-drunk with his rabblerousing, kleptomaniac, “more mature” girlfriend Audrey (Foster), is delighted to stick around by film’s end, too.

Though Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore nearly signs off with a Hollywood Ending (David coming to win back the affection of Alice at Mel’s after a rough fight, complete with the diner regulars clapping when all is resolved), there’s an appropriately ambiguous tag just before the film’s closing credits: Tommy and Alice walk away with their backs to the camera … toward a sign that coincidentally reads “Monterey,” their own version of an American Dream still slightly out of reach …

With Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore saying as much about the relatively new focus the mainstream was starting to bring to single mothers and their sons/daughters as so many other modern trends of the time, we’ll next week check back in on the “fringe” scene of LA in order to delve into a father-and-son relationship, courtesy Charles Burnett’s essential 1978 film Killer of Sheep.

MATHEW KLICKSTEIN is (for the time being) a Boulder-based writer/filmmaker who recently completed and has been touring his documentary on 80s/90s TV icon Marc Summers, On Your Marc, to be widely-released soon. His next book, Springfield Confidential: Jokes, Secrets, and Outright Lies from a Lifetime Writing for The Simpsons (co-written with lifetime series writer/producer Mike Reiss, foreword by Judd Apatow), will be released through Harper Collins this June. You can keep up with his regular shenanigans at www.MathewKlickstein.com.