A Conversation With Daniel Geller & Dayna Goldfine (HALLELUJAH: LEONARD COHEN, A JOURNEY, A SONG) Part 2

(Jonathan Marlow’s excellent, 3-part interview with Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, a Journey, a Song filmmakers Daniel Geller and Dayna Goldfine continues. Part one can be found here.)

Hammer to Nail: Long before the making of this film. which was the first version of ‘Hallelujah’ that you’d heard?

Geller: It is probably sitting on the shelf behind you. We still have a bunch of CDs but we had [Jeff Buckley’s] “Live at Sin‑é.” That, to my knowledge, was the first time I had heard the song. And we kept playing it! I knew that it was a Leonard Cohen song at that point.

Goldfine: We hadn’t done a deep dive. Basically, like many, many people who hear it for the first time through Jeff, we’d just assumed that he’d written the song.

HtN: That does happen a lot.

Goldfine: It still does.

Geller: You did. I didn’t because I looked!

[laughs]

Goldfine: To me, it was this heartbreakingly gorgeous song.

HtN: His version is pretty extraordinary.

Geller: It is.

Goldfine: I felt like, “I don’t even need to hear anyone else sing it.” Then, when we saw the concert and Leonard did it and he got down on his knees, it was like, “Oh!” Then all of the other versions… One of the fun things about doing a project like this, obviously, [was the chance to explore all of the other versions]. There is Rufus [Wainwright] and John Cale but we had never even known much about Brandi Carlile. I love her version.

HtN: Her version is fantastic. Absolutely. I’d never heard the k.d. lang version until I saw your film. She has an incredible voice, of course.

Geller: What I like about her version is that it is modulated with very quiet parts in there but when she is belting it, it doesn’t sound like some of the covers where you’ve got someone shouting the song. With k.d., you just see every emotion washing over her and into the song. It is so beautiful.

Goldfine: Once you start cutting, it tells you what can and can’t be in the film. It is just the nature of the beast. Myles Kennedy does this unbelievably gorgeous version. He ends up appearing in our film for a split second, but I wish we could have included his version.

HtN: Perhaps for the home video release…

Geller: There are all sorts of things to talk through. There are certain licensing things that have to be resolved. The other part of our agreement with the Cohen Family Trust, which we fulfilled right away at the end of the production, was that all of the raw material—all of the raw interview footage and all of the transcripts—are in their hands. That’ll become part of the Cohen archives for scholarly access. Those interviews, which ran for hours on end, are deep and rich in their own ways and they will become available. That happened with Something Ventured, where all of the raw footage is available online, I believe, at the Smithsonian and at Stanford University. Whatever online streaming extras might be out there, there is a bigger contribution that hopefully can be accessible.

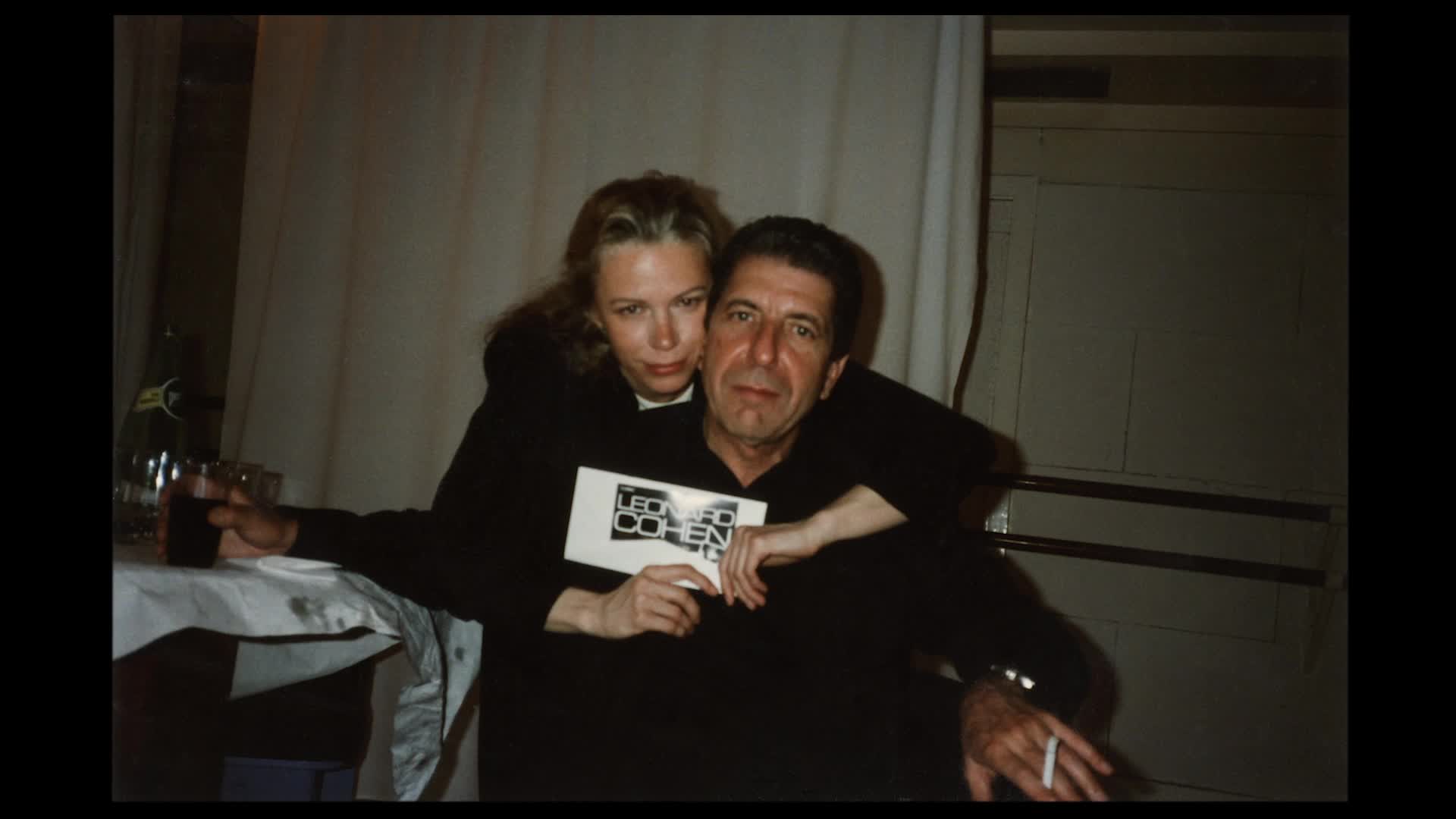

Leonard Cohen

Goldfine: It has been eight years since The Galapagos Affair was released. It is the first time we’ve come out with a film where there really isn’t much of a DVD market anymore.

HtN: Especially for music documentaries, I wager there is still an audience for that. Physical media is not dead. I insist on it!

Geller: Good. [laughs]

Goldfine: I agree.

HtN: Not totally dead.

Geller: When Michael [Barker at Sony Pictures Classics] made the pitch up at Telluride—”Come with us. Do this with us.”—he said, “We know how to do a movie like this. We know this is a movie that is going have decades of life. It is not going to disappear in a year or two. We’re committed to keeping it alive for all of those years.”

They seemed like such a natural partner for this particular project.

Geller: Yes.

HtN: And yet it wasn’t a done-deal from the get‑go.

Goldfine: Oh, no. No, no, no.

HtN: It seemed like it would inevitably end-up with them but there is nothing inevitable anymore, right?

Goldfine: No.

HtN: But the synchronicities of the company seemed to suggest that it was an ideal pairing.

Geller: I think so.

Goldfine: A lot of documentarians now—we are not among that group—go for the big payoff.

Geller: The instant payoff.

Goldfine: Not every Netflix or Amazon deal is the $12 million Boys State deal. Those are like unicorns.

Right, right, right.

Goldfine: Just by virtue of the streaming-versus-theatrical, you’re going to get more if you get a streaming deal, probably.

HtN: At least up-front.

Geller: Up-front, yes.

Goldfine: But I doubt that we’re ever going to get $12 million. That is not why we’re doing it.

HtN: For this project and your desire to have it screened in a theatrical setting, this is the way to do it.

Geller: I agree.

Goldfine: It was our hearts’ desire.

HtN: What do you think of the first version of ‘Hallelujah’ that appears on Various Positions?

[lengthy pause]

Geller: I have two thoughts about it. One, it is not my favorite version that he has sung. I think the version he sang later in life has more heft to it. More road-years of his life in it. On the other hand, as a portrait of that moment in 1984, of that man, it is completely compelling. It is really interesting and it is so different from everything that happened later. To me, I like that we have two bookends of the song in Leonard’s life.

Goldfine: I would say that some of my favorite verses weren’t in the first four-verse version. I am actually more moved by some of the deeper or more secular verses.

HtN: You mentioned the passing of time from when you get from the period when it was written to when he was back on the road. You see that primarily in his version of ‘Tower of Song.’ Words that were written earlier now have a different and more nuanced meaning when he is singing it at a later age.

Goldfine: That section in the film is one of my absolute favorites.

Geller: There is the verse that says, “I did my best, it wasn’t much.” He would’ve written that when he was age fifty, more or less. There is a certain truth to that moment saying it, at that age, but then, at age seventy-five, he is singing it. There is a whole other level of what that means to the writer/performer. You can see that. With the ‘Tower of Song’ sequence, Dayna and I both thought that we had to let it play at a much greater length than you would think for a movie about another song.

Goldfine: It is the longest chunk of non‑‘Hallelujah’ material but I think it might even be the longest. Actually, ‘If it Be Your Will’ is almost four minutes. There is a lot more woven in-between it in terms of straight concert time. I would say ‘Tower of Song’ has the most but that moment when Leonard turns to Sharon Robinson and the Webb Sisters and says, “Don’t stop,” I still cry when I see that. It is just so precious.

HtN: I first became familiar with ‘Hallelujah’ in John Cale’s version from Hal Wilner’s I’m Your Fan tribute project. I fortunately saw Cale perform it at one of his shows around that time. Then, of course, the Jeff Buckley version from Grace, which is such an impressive version. One of the things I’ve always adored about the song is how subversive it is in the ways that people will put whatever meaning they want into it. They’ll turn it into a very religious song even when the specific lyrics they’re singing are clearly not religious at all. Or, like Buckley and those inspired by his version, they’ll make it very sensual. The documentary uses this subversiveness to its advantage.

Goldfine: We’re trying hard not to tell the audience what we think it is about.

HtN: It is not helped by explaining it.

Geller: What I think is clear is that you deal with Judaism, you deal with Buddhism, you deal with the fact that this is already a conflict within him of finding a spiritual path and then the issue of having the song become a thing that very religious people embrace.

HtN: Although this isn’t what you think it is.

Geller: There is that liturgical rhythm to it. It invites you in for that. There is that incredible leap of the chorus which, again, invites you in. It is a very odd understanding of the song to choose to ignore half of what the song and any particular couplet is saying. In any couplet, there is one half that is putting a foot down in the land of religiosity or hope or faith and then another foot goes down talking about brokenness, carnality, lust and longing, failure. I don’t think people are willfully ignoring it. It is just that they are so seduced by one half of the couplet that their mind goes there and they don’t see the rest of it.

Goldfine: Or they just aren’t delving in. It is interesting because, for a long time, there was a scene in the film that we ultimately cut where the rabbi [Mordecai Finley] was talking about when people ask him to use it at weddings and funerals. “Why would you want that song at your wedding? It is such a dark song.” Then he said, “You know, there was this young girl in my congregation who, for her bat mitzvah, asked me to accompany her on my guitar as she sang ‘Hallelujah’. As I was watching her singing it…’ and he gets tears in his eyes in the interview as he says, “all I could think of was, ‘I hope it is a really, really long time before you know what this really means.'”

[laughter]

HtN: I suppose what I am gradually getting at is the way in which you put something out into the world and it begins to have its own life. How this theoretically forgotten song on an album the record label declined to release…

Goldfine: Track one, side B.

HtN:…becomes this phenomenon through these interpretations by other people. I hadn’t been aware until the film [and the book, subsequently] that Bob Dylan had been performing ‘Hallelujah’ live.

Goldfine: He was the first one.

Geller: There is a lot of humor in that song. It is dry, droll, sardonic humor which is very Bob Dylan. You could see why he would sing it.

Goldfine: Bob was fascinated. In Ratso’s tapes, there is a much longer section on Dylan and Cohen. Obviously, we cut everything way back. In one of the early versions, Ratso’s on tape talking to Leonard, because he has just come back from Bob, and Bob was actually repeating the verses from memory. It was before he actually sang it in concert. Leonard said, “I sent him of the verses.” Leonard was clearly proud of it.

HtN: I did not know any of that.

Geller: Dayna and I learned all of this in the course of making the movie. We didn’t know any of it either.

HtN: I have seen a number of other films made about his work. It could be said that he is a very difficult subject and that he wasn’t an easy individual to nail-down in any way. Elusive, perhaps. To try and tell an entire life of someone through a single song… although, granted, you’re not just using merely that song.

Geller: When we started making the movie, we didn’t realize that we were going to wind up with twenty-two other Leonard Cohen songs in the movie. We had no idea. The more we got into it, the more we realized that these songs illuminate his life. Also, you just want to live in these songs. We didn’t really anticipate that. We knew that there’d be a few others but not twenty-two! That was one of the surprises. When you mentioned earlier [before we started recording] that we take a fair bit of time before we even addressed the song or even the writing of the song, specifically, that was one of the harder things in the whole construction of the movie. We had to somehow, in crafting that first twenty-five minutes, whisper ever so quietly, “Don’t worry. We’re going to get there. Don’t worry.” There were a couple of very fine‑tuned things that we had to do to twiddle the knob a bit. As we were showing works in progress to people, that complaint disappeared. It was prominent early-on, with people saying, “It’s taking too long to get to the song.” In fact, ultimately, we probably got to the song maybe two minutes faster than in the initial draft, but they’re just little hints. Just to let you know, “We know you’re waiting for it.”

Dayna Goldfine and Daniel Geller

Goldfine: Also, a big change was moving the scene with Ratso up to the front. We left the opening of the film until the end to start cutting because, with the more films that you make, the more you realize that openings and closings are the ones that you cut and recut and recut forever. We decided to not even think about what the opening would look like. Once we started getting that feedback, you need to reassure people that they will get to ‘Hallelujah’ and starting with that scene with Ratso and Leonard…

Geller: Since we had access to the journals and notebooks at that point, we could represent it visually as well, to say, “Here it is. We’re going to come back to this. For now, let’s go to the birth of a songwriter.”

Goldfine: Also, Ratso saying in voiceover, “In order to really understand ‘Hallelujah’ you need to understand Leonard Cohen.” It gives us a reason…

HtN: …or gives you permission.

Goldfine: Exactly! Which you have to ask of your audience. It is a compact that you’re making with your audience that you are going to deliver to them what they’re hoping to get.

HtN: It is in the title! You shouldn’t have people buying tickets and then go, “What are we doing? Why exactly are we here?”

Geller: Bait-and-switch. [laughs] To come back around to your earlier question about how audiences have reacted in different countries, I would say that they’re self‑selecting to make that choice to see it at a film festival. You can feel it. People are moved. That is primarily what I hope for when I go to watch a movie: that I am moved in some way, whether it is to laughter or to introspection or tears. Whatever it may be. That is what I’ve felt in the screenings we’ve attended. Being able to sense that emotion in a room means that we’ve channeled Leonard because it really is coming from him. We’ve channeled Leonard without getting in the way. That is what you were feeling in those concerts. They move you. It’s not just the Stones playing their hits. [laughs]

Goldfine: I had something like cognitive dissonance when the film opened in Venice. I went to that screening on a Thursday and then flew the next morning to Colorado. Then, went to the next screening on a Saturday. A friend in Italy clued me into this before it even happened. He said, “You’re premiering this in a very Catholic country and you’re going to get a religious take on it.” He was right. You felt it. It was a much more pious audience. At Telluride, people laughed more. There are different cultural norms that each audience brings into the screening. If you showed it in Amsterdam… people there have a different relationship with Leonard Cohen than people in this country, I would say.

HtN: I can see that.

Goldfine: It is one of the things that is so gratifying about going to these different countries.

Geller: For that matter, on any given night in any movie theater, there is a chemistry that emerges. It’s a strange thing because we have friends who work in the performing arts. They’ll say, they’re up on stage and the audience is just on fire and then the next night, there is something that is just not happening. With us, the movie is the movie but it is still a strange experience to be sitting in the theater, thinking, “Wow, they haven’t laughed at this line.” People usually laugh, and then all of a sudden, you realize they’re crying. Those emotions are contagious.

Goldfine: That was definitely the situation in Venice. Like our friend said, “The audience is going to be very rapt and very quiet. That doesn’t mean that they do not like it.” Sure enough, at the end, there was an enormous standing ovation. I didn’t know that was going to be their response from the lack of audible noise during the screening.

Geller: I’m really curious about the reaction when we show it in Jerusalem.

HtN: That will be fascinating.

Geller: It will be fascinating.

HtN: Do you always make a point to sit with the audience?

Geller: Oh, yes.

Goldfine: In new countries, yes.

HtN: Is it possible that the Trust will publish the journals at some point? Seeing them in the film, seeing his writings…

Geller: I don’t know what their plan would be. I wouldn’t be surprised. I do know that they’ve created a beautiful lobby display that’ll be going out to many of the theaters that has the notebook‑page lyrics blown-up large along with a picture of Leonard.

Goldfine: That was Robert. I think it was even his idea. He said, “Why don’t you do a lobby display and I’ll give you one of the journal pages?” He has been amazing. Given that it started with, “Don’t ask for anything. We’ll stay out of the way.” In fact, Robert is the reason that we got the interview with Dominique Issermann. He called one day in December and said, “The universe wants this film to happen.” We said, “Really? Why?” and he replied, “Because you won’t believe who I just ran into at Leonard’s house. Dominique.” We said, “Did you ask her about the song?” And he said, “Yes. She told me that he wrote a lot of it in her house. I told her about your film and she’d be willing to talk to you.” Isn’t that wild?

Geller: We shot that [interview] in either August or September of 2016 when Leonard was still alive. She was staying at his house (but we did not shoot it at his house).

Goldfine: Robert paved the way and gave us her email. We ended up having a few phone conversations with her while she was in Paris. Then we reconnected her to John Lissauer. When we were about to interview John, we did a phone call so that they could reconnect for the first time since Various Positions.

Geller: One thing that Dominique mentioned—which goes to why Leonard had trusted us to do what we were doing—is [Cohen] said, “They’re not going to ask you, ‘Was it your kitchen chair*?’ It’s not going to be like that,” and Dominique understood. When we sat down with her, we said, “We don’t want specificity as far as ‘Leonard told me this, Leonard told me that’ or about what the song means.” In fact, she said such beautiful things. “It’s like a bird that is touching the walls of culture. It is very symbolic. It is very mysterious.” But what was beautiful was that she could talk about his creative process, which was really what, as much of anything, we were interested in. That goes back to Ballets Russes. I’m fascinated by the creative process.

HtN: It is the thread through all of your work.

Geller: It is.

— Jonathan Marlow [@aliasMarlow]