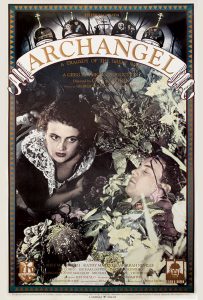

ARCHANGEL

(Check out Jonathan Marlow’s Archangel movie review. The film is part of Metrograph NYC’s “Zeitgeist Films at 35” series. Seen it? Join the conversation with HtN on our Letterboxd Page.)

Metrograph NYC [7 Ludlow St., Lower East Side of Manhattan] has spent recent days honoring the great Zeitgeist Films, founded by Nancy Gerstman and Emily Russo, on the occasion of its thirty-fifth anniversary. Their exquisite curation of unusual films and filmmakers—in particular, Jan Švankmajer, Astra Taylor, Stephen and Timothy Quay, Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller, Julie Bertuccelli and many, many others, including the early achievements of Todd Haynes and the later films of Derek Jarman—brought greater visibility to works that might otherwise be overlooked. Like an influential record label and eclectic book publisher, audiences always knew that an association with Zeitgeist meant that a film was absolutely worth seeing.

The Metrograph series concludes on 10-December yet in-between then-and-now is a curious highlight of the series, a far-too-rarely-screened Archangel, the U.S. premiere of a new 4K remaster funded by Telefilm Canada, with all of that extraordinary film-grain given digital luster. Guy Maddin himself was on-hand to discuss the film, pre- and post-screening on 1- and 2-December. [The repeat presentation on 6-December is evidently film-only but worthwhile on its own, regardless!]

Maddin’s connection to Zeitgeist begins with his debut feature-length, Tales from the Gimli Hospital (also recently remastered in 4K, presented as a Redux edition at the 2022 TIFF and elsewhere, subsequently). Gerstman and Russo gave the film an ambitious release that immediately amplified the distinct look-and-feel of his work from the beginning, only a handful of years after the company began. Their home-video release of the film included his short The Dead Father, getting in early on the “supplemental materials” habit quite some time before many other companies followed-suit.

If Gimli is a pseudo-silent film, his sophomore feature, Archangel, billed as a “Tragedy of the Great War” in all earnestness, is a pseudo-soundie, part-“talking picture” with occasional inter-titles. Set in the closing days of the First World War, a Canadian soldier arrives in the titular Russian town and falls for a local woman he mistakes for his deceased wife. Given that she is married to another, a ribald triangle of affections is formed between the three (and it clearly cannot end well for any of them). Despite such a straightforward summation of a plot, these details are merely a framework for tangents vast and miniscule, semi-related or unimaginable.

Placing this film in a Zeitgeist retrospective is something of a slight revision to history. At the time of its initial release, Archangel was, if memory serves, hardly distributed at all. Maddin’s third feature-length, an inspiration of genius entitled Careful, was handled by Zeitgeist and expanded Maddin’s reputation exponentially. Archangel had been a not-quite-missing but essential piece in the puzzle of Maddin’s career, much of which—except for films completed on behalf of other companies, such as The Saddest Music in the World—is available from Zeitgeist then-and-now.

Regardless, the reissue of the remaster allows for an opportunity to revisit an excerpt of a conversation from 2004:

Marlow: Then Archangel followed Gimli. It was given the National Society of Film Critics award for “Best Experimental Film.” Here you have this “part-talkie,” a beast which really only existed between 1927 and 1930, but you had to make one and there it is. Inter-titles, occasional dialogue, voiceover… everything all in one big picture. How was your experience on that film?

Maddin: I loved making that movie. I really thought right up until the day I had it finished that I’d made a masterpiece. I watched it for the first time during a process of the sound mix. It used to be called the interlock, where you’d put up all these magnetic soundtracks all at once really for the first time. Normally, when you’re editing on a Steenbeck, you can only hear two tracks at once. I think I only had three or four tracks on the movie, but I finally heard them all at once. I really felt like I’d made a dream, a perfect dream of a movie.

It wasn’t. I had no objectivity on it. I didn’t even realize until I watched it with an audience and then…it was very crushing. I didn’t have a test audience on the film in those days. I didn’t trust them. I didn’t realize that I’d made a film that was incomprehensible to everybody else. It wasn’t so much “dream-like” as “sleep-inducing.” But I feel that the completely self-deluding experience I had when I first watched Archangel might be one of the best film viewing experiences ever. I was very proud of myself when I watched it with Greg Klymkiw, who was my producer at the time, and we were just so thrilled at how beautifully it turned out. We both fooled ourselves. We just drove around all night going, “Wow, that is so incredible!” You know, we got our comeuppance.

Marlow: I think that it has a first in the history of cinema, though: the intestinal strangulation scene. I was quite surprised by that.

Maddin: I was proud of that. It felt like a first. If I stole it from anyone, it was definitely a subconscious plagiarism.

Marlow: It’s played seriously, which I think helps considerably. It is a very strange sequence, admittedly.

Maddin: [laughs] Thank you.

Marlow: I think this whole technique was pretty much fully formed by the time you get to Careful, where you’re making your first color film. I watched it again last night and I felt it to be a Freudian fever-dream. Until very recently, it was my favorite of your films.

Maddin: I feel Freud has been discredited. No one takes him seriously anymore. I thought it would be kind of fun to just embrace the good old days, when there was that great mania for Freud in the 1940s and 1950s in Hollywood. There were so many films with shrinks; sort of the Greek chorus. I thought it would be fun. I didn’t know much about Freud. I read the first chapter of his Interpretation of Dreams. It was really just fun to play around with these obvious symbols.

I was forced to do it in color by the distributor but I was really glad I was forced because it would have taken me a long time to get around to it otherwise. I was so respectful of the power of color, its mystical power. I started to try to harness it and control it as much as possible. I remember, I thought, “How could they force me to shoot color? Don’t they realise how difficult color is?” Think of Don’t Look Now where that red raincoat is worn only by a homicidal dwarf and a drowned girl. If you don’t control every color in the frame, you might accidently shoot a fire hydrant and the fire hydrant will take on all the same importance as the homicidal dwarf and a drowned girl. I didn’t want to have fire hydrants all over the place so I determined I would have to control the color of absolutely everything in the movie and make it only two colors at a time.

[A selection of works from the “at 35” series are also available via Metrograph at Home and, naturally, all are available from Zeitgeist on glorious physical media, beautifully assembled DVDs and Blu-rays aplenty!]

ARCHANGEL (1990)

dir. Guy Maddin [83min.] Zeitgeist Films

— Jonathan Marlow (@aliasMarlow) [Twitter ] | @marlowesque [BlueSky]