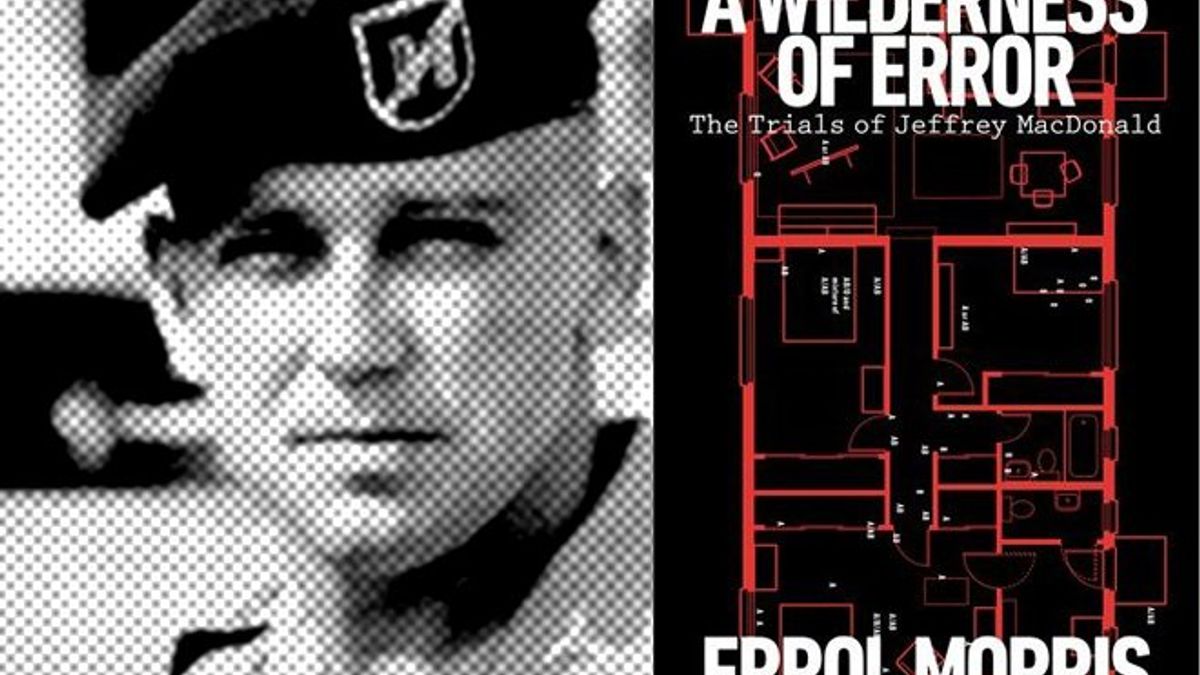

Errol Morris Gets Lost in A WILDERNESS OF ERROR

Emmy Award-winning and Academy Award-nominated Marc Smerling’s (Capturing the Friedmans, The Jinx) true crime docuseries A Wilderness of Error, which debuts on FX September 25, is completely addictive and utterly disturbing (and accompanied by an equally riveting and unnerving companion podcast, Morally Indefensible, out now). Based on the 2012 book A Wilderness of Error: The Trials of Jeffrey MacDonald by the OG of investigative doc-making Errol Morris, the five-part series is a deep-dive reinvestigation of the case of Jeffrey MacDonald, a former Army surgeon and Green Beret still serving time for the 1970 murders of his wife and two young daughters – a nightmarish crime he blames on Manson Family wannabes to this very day. It also contains the added bonus of serving as an accidental expose of Errol Morris himself.

Exhibit A: Morris’s chiding rhetorical questioning – on camera in a series of, ironically, Interrotron-style interviews – of what happens when the public narrative becomes the truth. (In one interview Morris even mentions that he feels like he’s addressing his cinematographic invention. Indeed, Smerling deftly manages to turn Morris’s tools on himself.) Morris is referring of course to famed journo Joe McGinniss’s bestselling 1983 book Fatal Vision (later turned into a two-part TV miniseries – ironies abound!) that made the case that the right man is indeed sitting behind bars, cementing MacDonald’s guilt in the public imagination. The fact that MacDonald worked with McGinniss on the book, under the assumption that it would exonerate him – and only learned of his journalist “friend’s” belief in his guilt during a “gotcha” interview with Mike Wallace on 60 Minutes – is the subject of an episode of Morally Indefensible. (The podcast’s title itself is a reference to the assertion by another famed journo, Janet Malcolm, whose own 1990 bestseller The Journalist and the Murderer took issue with McGinniss’ possible deception behind his relationship with MacDonald. Even though McGinniss worked with Malcolm on the book. Still with me? Good. Now back to Morris.)

Specifically (and ironically), Morris’s dire warning of the perils of the public narrative being perceived as truth as it relates to Morris’s own public MacDonald narrative. For lest we forget, Smerling’s docuseries is based on Morris’s bestselling take that casts doubt on McGinniss’s bestselling take. And yet Morris heedlessly ignores his own advice in service to the “wrongfully accused man” narrative he’s so clearly invested in.

Which, truth be told, shouldn’t be all that surprising – since the master at exposing the blindspots of others has, time and again, stubbornly refused to reckon with his own blindspots. (For proof, look no further than Morris’s glowing Theranos commercial with Elizabeth Holmes, or 2018’s softball American Dharma starring Steve Bannon – both now indicted fraudsters.) And yet, Morris’s blithe assertion that because Helena Stoeckley – one of the supposed killer hippies, and an unreliable narrator to say the least – had been confessing to the crime for nine years it somehow lent credence to her claim is still maddening. Was he suggesting that the repeating of a story often, and for long enough, somehow makes it real? (Even the judge who barred all those who heard Stoeckley’s multiple confessions from testifying at MacDonald’s trial wasn’t buying this flimsy argument, rightly concluding that the hearsay wasn’t relevant to the case.)

This is some dangerous territory Morris is entering. Not just because false confessions have been proven so prevalent, but because Morris himself is unable to see past his own flawed narrative. Indeed, Morris even confesses at one point to Smerling’s lens that he was hoping for a repeat of his Thin Blue Line exoneration success story – exoneration of course, ironically, also being McGinniss’s original intent. The difference is that, whatever one might think of McGinniss’s troubling tactics, he was able to follow the story to the “inconvenient truth” it ultimately illuminated; whereas Morris refused to stray from his happy ending. McGinniss aimed for investigative journalism, Morris for the three-act structure of fiction.

Read Lauren’s interview with Marc Smerling here.

– Lauren Wissot