A Conversation With Justin Kurzel (THE SNOWTOWN MURDERS)

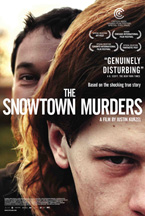

If you’re in the mood for some light, fluffy fare, don’t go anywhere near Justin Kurzel’s The Snowtown Murders (original title: Snowtown). Which isn’t to say that you shouldn’t see it. It’s just that Kurzel’s recounting of the horrific serial killings that plagued South Australia, Australia, in the 1990s casts a pall of bleakness that might very well make you sick to your stomach. Kurzel and screenwriter Shaun Grant find their window into this somber world through the eyes of teenager Jamie Vlassakis (newcomer Lucas Pittaway), a sexually abused teenager who falls under the charming spell of his mother’s new boyfriend, the sadistic and cunning John Bunting (Daniel Henshall). After winning a Special Jury Prize at Cannes’ Critics Week, The Snowtown Murders has continued to devastate audiences at fests around the world. Picked up for distribution by IFC Films, it opens theatrically in New York City on Friday, March 2, 2012, and ***is available on VOD right now*** (go here to learn more). This conversation took place at the 2011 Toronto International Film Festival, where Tom Hall sat down with Kurzel for a lengthy discussion about what drew him to the material, as well as his determination to tell this story from the sensitive perspective of an insider as opposed to the sensationalist viewpoint of an outsider. (Michael Tully)

If you’re in the mood for some light, fluffy fare, don’t go anywhere near Justin Kurzel’s The Snowtown Murders (original title: Snowtown). Which isn’t to say that you shouldn’t see it. It’s just that Kurzel’s recounting of the horrific serial killings that plagued South Australia, Australia, in the 1990s casts a pall of bleakness that might very well make you sick to your stomach. Kurzel and screenwriter Shaun Grant find their window into this somber world through the eyes of teenager Jamie Vlassakis (newcomer Lucas Pittaway), a sexually abused teenager who falls under the charming spell of his mother’s new boyfriend, the sadistic and cunning John Bunting (Daniel Henshall). After winning a Special Jury Prize at Cannes’ Critics Week, The Snowtown Murders has continued to devastate audiences at fests around the world. Picked up for distribution by IFC Films, it opens theatrically in New York City on Friday, March 2, 2012, and ***is available on VOD right now*** (go here to learn more). This conversation took place at the 2011 Toronto International Film Festival, where Tom Hall sat down with Kurzel for a lengthy discussion about what drew him to the material, as well as his determination to tell this story from the sensitive perspective of an insider as opposed to the sensationalist viewpoint of an outsider. (Michael Tully)

Hammer To Nail: When you’re dealing with crimes of this nature, as a storyteller who’s making a narrative fiction piece, you have a lot of different competing responsibilities. There are the responsibilities to the facts of the case, there’s the responsibility to the audience to tell a compelling story as a film, but one of the things that I found brilliant is how you metered out information to do both of these things at once. Can you talk about the structure of the movie and how you dealt with those competing or complementary responsibilities?

Justin Kurzel: Well, I definitely didn’t want it to be judgmental. I felt as though I needed to be a little bit more distant with it and observe, and not feel as though at every point I was making a judgment on each of these characters. I mean, to me the most important thing was having empathy for the characters and to be able to, I guess, see a different perspective as to what—especially in Australia—was being reported in the media, which was pretty one-dimensional. It was really a bit of a freak show, you know, “The Bodies In The Barrels”. To me, when I read the script, I came from the area—I was born in the area—and knew it really well, and I was just very curious as to why and how it happened. The community and the situation and the environment maybe had a little bit more to do with how some sort of evil came out of this place than it just being some “out of the blue” tragedy.

The script was probably more genre-based at the beginning, it had police in it, but what I found most compelling was this point-of-view of Jamie Vlassakis, an 18-year-old kid who’s kind of an innocent, living in this place where he’s suffering from sexual abuse and living with it and has a kind of apathy about his own life. And then along comes this guy who becomes a kind of father figure to him, gives him an identity and a voice, and tries to toughen him up and make him angry, and then exploits him into this world of evil. I found that incredibly compelling and interesting. So I guess the structure of the film and the voice of the film really came from Jamie.

The script was probably more genre-based at the beginning, it had police in it, but what I found most compelling was this point-of-view of Jamie Vlassakis, an 18-year-old kid who’s kind of an innocent, living in this place where he’s suffering from sexual abuse and living with it and has a kind of apathy about his own life. And then along comes this guy who becomes a kind of father figure to him, gives him an identity and a voice, and tries to toughen him up and make him angry, and then exploits him into this world of evil. I found that incredibly compelling and interesting. So I guess the structure of the film and the voice of the film really came from Jamie.

The beginning of the film’s quite observational, it’s probably more of a social realist piece. You’re watching it from a distance and there are all these characters, and you’re kind of waiting for something to happen. And then as the film progresses and you become more involved in the John/Jamie relationship—especially after what I call “the initiation,” which is the murder of his brother—I think the film shifts quite dramatically and becomes much more impressionistic and deals more with the internal voice of Jamie. I was really interested in that style of storytelling, and, yeah, I guess staying away from the decoration of the event. Like, dates and all that sort of stuff, I just wasn’t interested. I was much more interested in this relationship and how a kid like this could be exploited in such an easy and horrifying way.

H2N: I wanna go back to the thought you had about the community in the North Adelaide suburbs. Watching the film, community for me was operating on two levels. There’s this community of people that are all together, and that’s the community from which the victims are generally selected. And then there’s this complete absence of authority or any sort of concern about the outside world with this group of people. There doesn’t seem to be a foundational community outside of their group at all. There are no worries about the police. It’s not even mentioned. It’s not a thought in the characters’ minds. They’re really hyper-focused on this local thing. What is that a reflection of, aside from the criminals and the specifics of their case?

JK: I think it was definitely exaggerated more in the film, but this is a place that has been underprivileged for probably about 40/50 years, it’s gone through generations of sexual abuse, especially child abuse. It’s a community that’s had a mistrust of authority, that’s felt as though when they had spoken up about certain crimes or whatever that nothing’s really been done. So I think it was a community without a voice and that has been living within its own kingdom, I guess. I’m really fascinated with how those sorts of communities close down and become as small as a pea and then kind of have their own rules. I wanted the film to feel like it was John’s kingdom and that even if Jamie wanted to walk out and go to a police station, he couldn’t. That John was so cunning in the way he made everyone complicit in the events and he closed down this world that it was a fortress and there was no way of getting out. I do find that interesting because I do think in society we close down our worlds and suddenly certain figures become our kings and queens, and we are heavily influenced by their power. And I definitely felt like that when I was doing my research with this. So I think first of all mistrust of authority from past experiences and a kind of apathy.

The film is kind of like a western at the beginning. Everyone’s stagnant and apathetic and is allowing shit to happen to them. And this guy rolls in on a motorbike and says, “This is wrong. Your brother fucking you is wrong, and that guy over there doing what he’s doing is wrong, and you’re not weak, you’ve gotta start standing up for yourself, you’ve gotta have a voice.” I found it really compelling that even when you read the book and were so disturbed by the carcass of brutality in these people’s lives and how they could become so exploited, that when John came into the book and he arrived in this place, there was this strange thing of, “Wow, it’s a breath of fresh air.” This guy’s come in and given them stability and a voice and empowered them and is listening to them. I found that really powerful in terms of where he can take them, and how he exploits them.

The film is kind of like a western at the beginning. Everyone’s stagnant and apathetic and is allowing shit to happen to them. And this guy rolls in on a motorbike and says, “This is wrong. Your brother fucking you is wrong, and that guy over there doing what he’s doing is wrong, and you’re not weak, you’ve gotta start standing up for yourself, you’ve gotta have a voice.” I found it really compelling that even when you read the book and were so disturbed by the carcass of brutality in these people’s lives and how they could become so exploited, that when John came into the book and he arrived in this place, there was this strange thing of, “Wow, it’s a breath of fresh air.” This guy’s come in and given them stability and a voice and empowered them and is listening to them. I found that really powerful in terms of where he can take them, and how he exploits them.

H2N: It did have a political aspect of almost a community organizer against the boogeymen of pedophiles and homosexuality that he rallied everybody around and then implicated them all in his own perverse reaction to that. That draws me to the idea of masculinity in the movie, which is very, very powerful. I know different cultures have different masculine tropes and things of that nature. In this case, you get the sense from the women characters especially, who are tossed to the sideline eventually with this permissive “boys will be boys” mentality. They do suffer. We see them suffering by the decisions and the actions and their complicity in what’s going on. But at the same time, it’s almost understood that this is how the men operate. Can you talk about how you saw that?

JK: I think in any community that has dealt with or is going through large numbers of kids who have been sexually abused or there’s been a history of sexual abuse, I think there is always this kind of search for sexual identity. And whether that search for sexual identity is expressed through violence. To me, that was something very, very interesting. You know, that this kind of almost over-stretching to prove one’s masculinity and identity was really strong. I definitely think that’s a huge part of the psychology here and how men are interacting with each other in the film. But definitely part of Australian culture is that very bronzed Aussie, very strong, physical, go out hunting, shooting [kanga]roos. In the country there is a very strong tradition of those very strong alpha male figures, and they are who are celebrated, from our sportsmen to our heroic figures in the war. It’s a very rite-of-passage thing for Australian men, which often conflicts heavily if you are not that or don’t come from that. I definitely think John has that alpha male presence about him, but at the same time that complication of his past and, I guess, dealing with the sexual abuse around him and how he then redefines and re-identifies the characters that have gone through that abuse.

H2N: One of the interesting things watching the movie as an American is we had our own kind of pedophile scare, really a mass hysteria, in the ‘80s, where people were convicted and put in jail for stuff that never happened. Police went crazy asking children about sexual abuse that potentially never happened to them—the kids were coerced into making statements. It was all over the country. So there was skepticism from my point-of-view when the community was reacting this strongly, until you saw the sons being actually abused and the brother abusing the other brother. But it also makes me wonder if there was that hysteria in the country or in the culture at that time.

JK: In the North Adelaide community there is.

H2N: And it’s real.

JK: Absolutely.

H2N: So that’s different.

JK: I mean, it still is.

H2N: What do you think is the root of that? Poverty?

JK: I think there are many things. Especially in this community. Yeah, unemployment, under-privilege, poverty, social planning, depression. I think there are many things, and then patterns of behavior. When I was reading the transcripts and the books about this, most of the characters had been sexually abused. I mean, we’re talking about the mother, and then, what’s extraordinary was that her mother had been abused. So that kind of lineage of sexual abuse, it just kept on repeating itself and continuing, to the point where it became kind of normal. It was interesting, we were talking about it before, but even the rape scene between John and Jamie, I always kind of asked, “Why didn’t this 18-year-old kid, who physically looked like he would be able to fight back, fight back?” That’s what’s so horrific about the events. Here was a kid that could but had been abused by his own brother, and it got to a point where it became normal and he just let it happen. And that’s what’s so tragic about it is that suddenly your universe has accepted this as normal and it’s not. So I don’t have a singular answer but I do see patterns that are very familiar.

JK: I think there are many things. Especially in this community. Yeah, unemployment, under-privilege, poverty, social planning, depression. I think there are many things, and then patterns of behavior. When I was reading the transcripts and the books about this, most of the characters had been sexually abused. I mean, we’re talking about the mother, and then, what’s extraordinary was that her mother had been abused. So that kind of lineage of sexual abuse, it just kept on repeating itself and continuing, to the point where it became kind of normal. It was interesting, we were talking about it before, but even the rape scene between John and Jamie, I always kind of asked, “Why didn’t this 18-year-old kid, who physically looked like he would be able to fight back, fight back?” That’s what’s so horrific about the events. Here was a kid that could but had been abused by his own brother, and it got to a point where it became normal and he just let it happen. And that’s what’s so tragic about it is that suddenly your universe has accepted this as normal and it’s not. So I don’t have a singular answer but I do see patterns that are very familiar.

When we were talking about it with the cast, who are all non-actors—apart from Daniel—we would sit around and rehearse the dinner table scenes. A lot of those conversations were very real for those people living there. All of them had many stories of pedophilia in the area, and were still very, very angry. And these things had happened ten years ago yet these issues felt very real and contemporary.

H2N: Did they improvise those conversations?

JK: Yeah. They were improvised. Some of the stuff came from them and then also some of the stuff came from the script. So it was a combination of Dan, who was playing John, checking a few lines from the script. It was really interesting, because even though it was kind of improvised and a lot of it was coming from them, they were still aware that they were on camera and there was a light there and we had two cameras going and Dan was acting and putting in lines, so it was an interesting kind of riffing between real life and real experiences and a film.

H2N: It also gives his character a sense of mastery on the screen more than everyone else in terms of his performance. Everyone else is very naturalistic and they have these weathered faces, you can tell they’re real people. And he has a very charismatic, powerful screen presence based on his performance, and I think that dynamic works very well to convey his power over that group.

JK: That was very deliberate. Dan was outside the community like John was. John came from a different place and arrived. So Dan was a Sydney actor who was middle class and had never done anything like this before, and suddenly arrived at this place. He was there ten weeks before and I got him to start eating shitloads of junk food and start putting on weight and then starting to hang out with the cast and be in the community. What I didn’t realize, ‘cause I was looking for an actor who—there were many actors in Australia who wanted this role—we didn’t want it to be this cliché serial killer. I said to Dan, “The most important thing is that you need to develop very quick relationships and be very social, which John was, and that is what your dynamic is. It’s not about anything else but that. It’s about your seduction and your real interest in the people around you. So when he arrived, I had no idea that all these people started coming up and getting his autograph. I didn’t realize that he was in this soap, Dan didn’t tell me about it. [H2N laughs] If he had, I don’t know if I would have hired him or not. But it was fantastic, because he was walking around and everyone knew him. The soap played at three o’clock in the afternoon, because everyone was unemployed they all watched it. So everywhere he went people gravitated toward him and wanted to talk to him, and Dan’s really social and talked back, so it was really great that straightaway he had this instant position of authority and adoration.

JK: That was very deliberate. Dan was outside the community like John was. John came from a different place and arrived. So Dan was a Sydney actor who was middle class and had never done anything like this before, and suddenly arrived at this place. He was there ten weeks before and I got him to start eating shitloads of junk food and start putting on weight and then starting to hang out with the cast and be in the community. What I didn’t realize, ‘cause I was looking for an actor who—there were many actors in Australia who wanted this role—we didn’t want it to be this cliché serial killer. I said to Dan, “The most important thing is that you need to develop very quick relationships and be very social, which John was, and that is what your dynamic is. It’s not about anything else but that. It’s about your seduction and your real interest in the people around you. So when he arrived, I had no idea that all these people started coming up and getting his autograph. I didn’t realize that he was in this soap, Dan didn’t tell me about it. [H2N laughs] If he had, I don’t know if I would have hired him or not. But it was fantastic, because he was walking around and everyone knew him. The soap played at three o’clock in the afternoon, because everyone was unemployed they all watched it. So everywhere he went people gravitated toward him and wanted to talk to him, and Dan’s really social and talked back, so it was really great that straightaway he had this instant position of authority and adoration.

H2N: I don’t know if this is something you don’t want talked about in discussions of the film, is the use of the voicemails and the way that you handle violence in the movie. It’s very effective and a very interesting choice. Why the decision to use that technique, which is atypical and unique for the familiar serial killer genre?

JK: First, about the violence, I didn’t want it to be the leading character in the film, I wasn’t interested in making a horror or slasher film. The violence needed to always come through the characterization and point-of-view of Jamie. So out of the twelve murders that happened, there was only one amongst them that we wanted to bring to the screen, and that was the murder of the brother. It was the biggest initiation for Jamie that John got him to do. It’s also the moment that you see John and his relationship with death and taking someone’s life and the power and pleasure in that, which I thought was very important to see in contrast to how he was before, which was just preaching an ideology. And how in that moment we saw the corruption of that. But I think the main thing was that I just felt that the violence on screen had to be extremely real and there had to be a cause-and-effect to it, and it had to a little bit like a car crash. It had to be a very visceral experience. I didn’t want the audience to have a compass, in that I think in most genre horror films you always have a compass watching it as an audience member and so you’re able to feel safe with it and watch it from a distance and be above it a little bit. Whereas this I wanted it to be completely disorienting like violence is in real life. And also that comes out of banality and domesticity, which is what was so horrific about these scenes that happened over two days. The TV would be on in the background, kids would be playing out in the backyard. This violence wasn’t exaggerated. It was coming out of very real and ordinary lives. The coexisting of those two things I found so terrifying and so interesting. I don’t think the film is very explicit if you put it up against Inglourious Basterds, but I think what disturbs people so much is the reality of it, because it is claustrophobic and psychological…

H2N: And it’s true.

JK: Yeah. The film is pretty unrelenting, but I don’t apologize for that, because I think that it kind of needs to be. So that was always our rule with the violence: it needed to be deeply connected to the characterization of Jamie.

H2N: I wanted to ask about Jamie, and the choice of keeping it to his perspective, his initiation into the world. You pay a price a little bit with the film, in that it excludes some of John’s other crimes that are prior to Jamie’s consciousness of them. And you throw a very specific set of brackets around Jamie’s experience leading up into a visualization of this one case when he kills his brother but also later on when he starts courting victims. Talk about why Jamie is such an effective voice—I know he’s also the person who was witness for the state against John and everybody else. Why Jamie as the eyes into this world?

JK: He’s the only character who, I guess, starts off as an innocent, and then leads you into a hell through his point-of-view, and leads you possibly to the point of being a killer. To me, that was the most interesting segue into it. It was also… through his point-of-view it allowed me to edit so much of the information and events, ‘cause it’s really confusing. I was just most interested in the events that affected Jamie and it allowed me to reveal the murders much later, because obviously John was involved in stuff before he met Jamie. So it allowed us to set up a completely different character at the beginning with John and experience what Jamie did, that kind of, “Wow, this incredible man’s come into my life, things are great, this is good.” And then, suddenly, being fooled, trapped and then led towards a kind of purgatory or evil where there was no return.

— Tom Hall