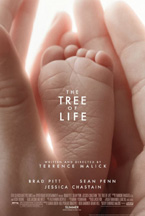

(Winner of the Palme d’Or at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, The Tree of Life is being distributed by Fox Searchlight. It is now available on DVD and 3-Disc Blu-ray/DVD Combo + Digital Copy. It opened theatrically in New York and Los Angeles on May 27th, 2011 before expanding throughout the country in the following weeks and months. Visit the film’s official website to learn more.)

The Tree of Life is, all at once, Terrence Malick at his most intimate and far-flung. It vacillates between the filial and the celestial, the birth of a child and the birth of the universe, dwarfing such descriptors as “epic” and “ambitious” along the way. Its greatest feat isn’t merely its vastness but the fact that, the further outward its scope expands, the more it contracts back into itself. Malick’s film, seemingly aeons in the making but actually the result of some forty-odd years of preparation and development, is a kaleidoscopic assortment of thoughts, voices, images, and feelings ranging from dinner table quibbling to cosmic tranquility. Disparate though these setpieces may at first seem, Malick links them all together. The roots from which this tree springs forth—a boy named Jack trying to reconcile the two conflicting worldviews of grace and nature imparted upon him by his mother and father, respectively—is a simple one, but, like the various forms of life Malick depicts, its branches are as numerous as they are complex. This is form and content at their most wondrously unified, as well as Malick at his most nakedly autobiographical: The Tree of Life‘s tragic narrative catalyst was plucked straight out of the filmmaker’s young adulthood. It isn’t just the film’s cosmic scale that makes this feel like the culmination of a career in film. Never before has Malick shone his bright cinematic light onto himself in this way, resulting in a work as steeped in remorse as it is conceptually enormous.

Each of Malick’s previous four films is a period piece, a standard The Tree of Life both adheres to and ignores. The bulk of its narrative is set in a suburb of Waco, Texas (where Malick himself grew up) in the 1950s, but Malick also goes back, way back in time—there are dinosaurs, if you hadn’t heard—and steps into the near-present for the first time. Here the director is deeper inside his own head than ever before; out of that space he extracts grief-laden memories and grand takes on the nature of existence in equal measure. As above so below, and each thread of the domestic drama involving young Jack, his parents, and two brothers is interlaced with celestial imagery. Malick’s yarn is cosmic, but it’s also elemental. He asks much of his audience in that The Tree of Life‘s fragmented narrative grapples with Big Questions in a heretofore unseen way, but also keeps the reins on the small details that imbue it with such grandiloquence. Every pyramid begins as a grain of sand, every tree as a sapling. Malick’s skill for displaying both sides of the equation simultaneously may well be unparalleled.

Each of Malick’s previous four films is a period piece, a standard The Tree of Life both adheres to and ignores. The bulk of its narrative is set in a suburb of Waco, Texas (where Malick himself grew up) in the 1950s, but Malick also goes back, way back in time—there are dinosaurs, if you hadn’t heard—and steps into the near-present for the first time. Here the director is deeper inside his own head than ever before; out of that space he extracts grief-laden memories and grand takes on the nature of existence in equal measure. As above so below, and each thread of the domestic drama involving young Jack, his parents, and two brothers is interlaced with celestial imagery. Malick’s yarn is cosmic, but it’s also elemental. He asks much of his audience in that The Tree of Life‘s fragmented narrative grapples with Big Questions in a heretofore unseen way, but also keeps the reins on the small details that imbue it with such grandiloquence. Every pyramid begins as a grain of sand, every tree as a sapling. Malick’s skill for displaying both sides of the equation simultaneously may well be unparalleled.

Jack’s parents are certainly vessels for two huge concepts, but they’re also nuanced characters. The former trait is signified most immediately by the fact that neither is given a first name; they’re simply referred to as Mr. and Mrs. O’Brien. The subtle shadings that make them who they are as parents and as people are more difficult to discern, but no less present. If the father is the Darwinian harshness of the world, then the mother is its consoling gentleness. Nature vs. nurture—it’s been touched on before to hugely varying degrees but Malick uses it a a sort of cosmic thesis statement. Out of this duality comes the chance to notice that Mr. O’Brien is a music-lover frustrated at his inability to rise among the corporate ranks, a frustration that no doubt accounts for much of his surliness. But he’s neither a violent man nor a drunk. He’s as quick to remind his children he loves them as he is to blow up at them over seemingly minor things, and Jack’s resentment toward him can be puzzling at times. (If Jack is indeed a stand-in for Malick, then perhaps the full details of this particular relationship were excised for obvious reasons.) Similarly, Mrs. O’Brien is a woman who loves her children deeply but understands her husband’s pain too well to fault him for his strictness—she’s empathetic to a fault.

Despite its abstraction, The Tree of Life is in some ways Malick’s most straightforward film. It’s nonlinear in certain regards, but much of the spacetime footage exists separately from the main narrative, allowing Malick’s primary subject of Jack and his family to come to the fore. Here kids playing in the late afternoon sun—moments which, like all others in the film, are captured with a breathtaking sense of grandeur by Emmanuel Lubezki of The New World and Children of Men, among others—are elevated to the status of Titans roaming Olympus. The team of Malick and Lubezki is one that finds the inherent beauty and sorrow in all things, from a butterfly flapping its wings to row after row of sunflowers backlit by the sun. Lubezki’s camerawork is breathtaking no matter the subject, but suffice to say that The Tree of Life‘s vastness suits his aesthetic well. Light dominates the film, whether falling across the face of its characters or the surface of a distant planet. There are many unifiers here; this is one of them.

Despite its abstraction, The Tree of Life is in some ways Malick’s most straightforward film. It’s nonlinear in certain regards, but much of the spacetime footage exists separately from the main narrative, allowing Malick’s primary subject of Jack and his family to come to the fore. Here kids playing in the late afternoon sun—moments which, like all others in the film, are captured with a breathtaking sense of grandeur by Emmanuel Lubezki of The New World and Children of Men, among others—are elevated to the status of Titans roaming Olympus. The team of Malick and Lubezki is one that finds the inherent beauty and sorrow in all things, from a butterfly flapping its wings to row after row of sunflowers backlit by the sun. Lubezki’s camerawork is breathtaking no matter the subject, but suffice to say that The Tree of Life‘s vastness suits his aesthetic well. Light dominates the film, whether falling across the face of its characters or the surface of a distant planet. There are many unifiers here; this is one of them.

A series of one-sided conversations—between a believer and his God; between a father and his son; between a boy and his brother—comprise much of the film. For its entire first hour, there are very few “scenes” to speak of. Malick’s characters rarely speak to one another for more than a few sentences at a time, and their most telling moments are those wrought in solitude, when they’re at their most desperate. Numerous voices can be heard in The Tree of Life, but two are conspicuously absent: those of God and Jack’s brother. Nearly all of the voiceovers are addressed toward one of the two, and it’s a matter of debate as to who speaks to whom. “Why should I be good if you aren’t?” Jack asks, and we assume he’s speaking to God. His question is in keeping with the film’s epigraph, which is taken from Job 38:4,7:

“Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth? When the morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy?”

The Tree of Life isn’t Malick’s 2001; it’s his Sistine Chapel. Much of the film is as unequivocally and overtly religious as this quotation. Revelatory in both the Biblical and personal sense of the word, it’s a cinematic pilgrimage to the furthest reaches—of time and space, yes, but, far more importantly, of one’s own being—that always returns to the self. (Given these overtones, we know what Mr. O’Brien—himself something of an Old Testament God—means when he asks Jack whether he loves his father.) The result is as awe-inspiring as it is emotionally involving. If the concepts of grace and nature with which Jake wrestles are mutually exclusive (and who’s to say whether that’s the case), they are perhaps the only elements of the film: The Tree of Life is a film of intermingling in which the death of a child is as thematically vital as the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs. It feels like nothing short of a masterwork whose mysteries will, appropriately, take years if not longer to unlock. It’s divisive not in intent but certainly by its very nature of existing as a huge-but-fragmented work.

Malick hasn’t given in an interview regarding himself or his own work in over thirty years, and perhaps he no longer needs to: The Tree of Life is the 67-year-old filmmaker bearing his soul in the only way he seems to know how. The language he speaks in order to do so is an unmistakably spiritual one, but his is a film that wants to put you under its spell. Let it.

— Michael Nordine

John

“Much of the film is as unequivocally and overtly religious as this quotation.”

A statement like this should be questioned in the light of this:

http://reviewingtreeoflife.blogspot.com/

Just one question for movie lovers:

From which film was taken the idea of the girl getting asleep and awaking as a woman on a swing (Grace vs Nature speech)?

From the beginning of Sternberg’s “The Scarlet Empress”.

Do you think that Sternberg rhymes well with Kempis?

This is Devil and God.

Yes, this is “a film that wants to put you under its spell”. Be very prudent to accept this.

“If you’re good, people take advantage of you”, father warns Jack in the movie.

Pingback: HOME VIDEO PICKS – Hammer to Nail