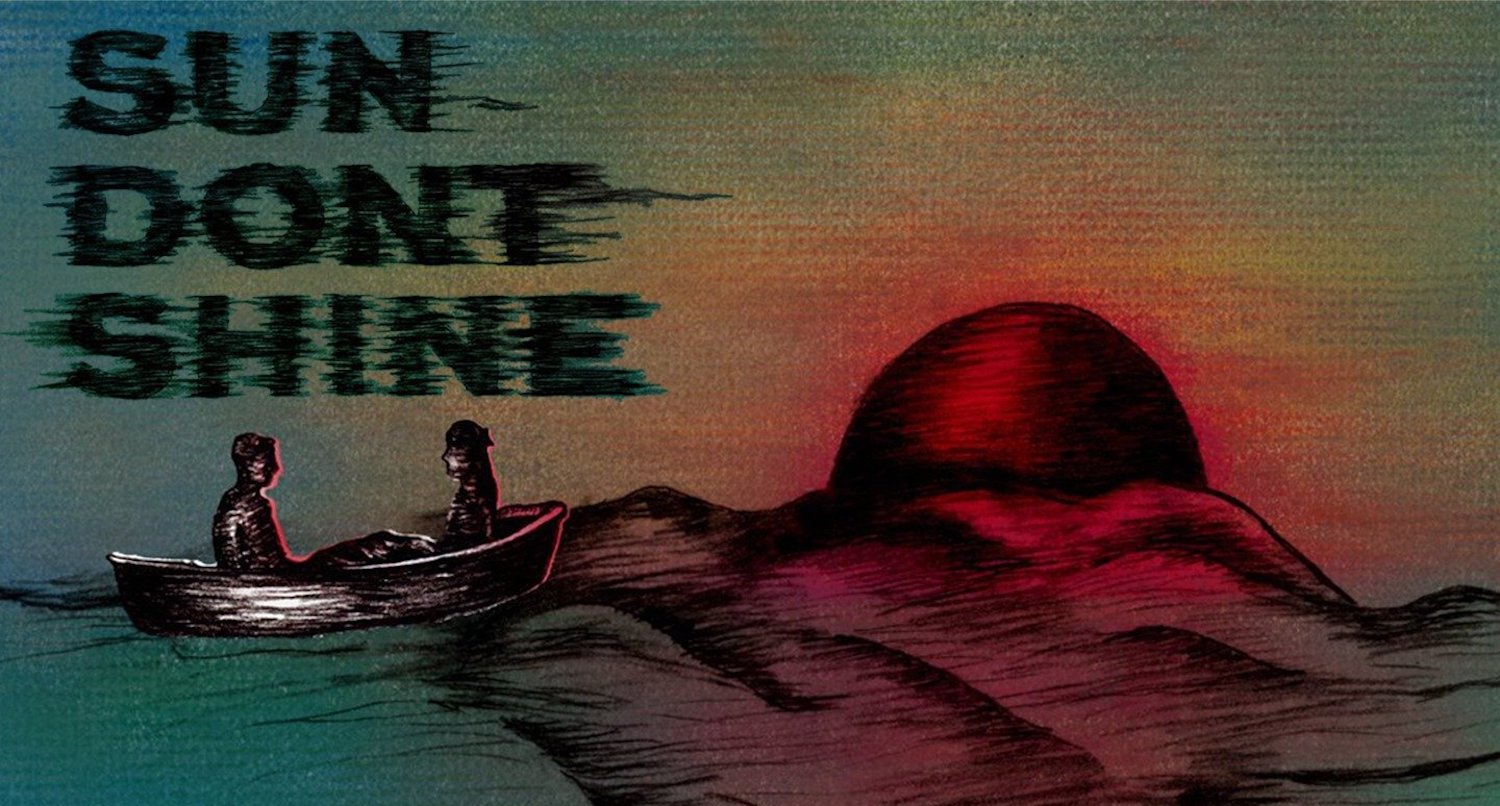

(Sun Don’t Shine is being distributed by Factory 25 and opens theatrically on April 26, 2013, in NYC and Seattle, in addition to becoming available on VOD. It world premiered at the 2012 SXSW Film Festival. Visit the film’s Facebook page to learn more. NOTE: This review was first published at Hammer to Nail on November 29, 2012, in conjunction with the film’s ‘Best Film Not Playing At A Theater Near You’ nomination, and it was also published as a “Pick of the Week” review for Filmmaker Magazine on Thursday, April 25, 2013.)

We hear it before we see it. A sharp, resounding slap jumps out from the soundtrack. Milliseconds later, the first jittery, violent, sweaty images of Amy Seimetz’s Sun Don’t Shine flash across the screen. A young man and woman, probably mid-20s, drenched in mud, fighting by the side of the road. Their pushing, shoving, grabbing, and shouting seems mutual—however, only seconds in, questions that will come to haunt the entire movie have already been aroused. Who started the fight, and over what? Who is attacking, who is defending? There’s obviously passion crouched behind their punches, but is it love or hate? It’s not entirely clear who delivered and who received that initial slap, but certainly no one feels it more deeply than the viewer. It’s a smack in our face, a gutsy, fearless introduction from Seimetz, a clear sign that in this first feature of hers, she is in complete control of the cinematic palette, and she’s not afraid to experiment with elements to shock, disturb, or provoke the audience.

Days later, that one-hell-of-an opening scene seems all the more impressive for how much emotion, meaning, and narrative is packed into such a short span of time. Like the punchy, hardboiled language of Dashiell Hammett and the Black Mask boys of the 1920s, Sun Don’t Shine’s images don’t waste any time; anticipation and frenzy emanates from every frame, leaving the audience with bated breath. A more compelling and original mystery hasn’t hit the screen in years. And yet, it almost feels improper to call it a “mystery,” even though that’s exactly what it is. Seimetz skirts the boundaries of the genre, dispensing with the expected clichés and archetypes, but at its heart Sun Don’t Shine is a lovers-on-the-run tale in the mold of Edward Anderson’s Thieves Like Us (filmed as Nicholas Ray’s They Live By Night) or Joseph H. Lewis’ masterpiece of B-moviedom, Gun Crazy.

Like its forbearers, Sun Don’t Shine focuses on two people, Crystal (Kate Lyn Sheil) and Leo (Kentucker Audley), in flight. Their relationship is never clearly defined, nor is the past they are running away from or the future they are rushing towards. All we know is that, as Leo unconvincingly consoles, “We don’t need to keep talking about this, but we need to keep going.” Tampa is only four to five hours away, he reminds her. So, they get in their car and they drive.

Like its forbearers, Sun Don’t Shine focuses on two people, Crystal (Kate Lyn Sheil) and Leo (Kentucker Audley), in flight. Their relationship is never clearly defined, nor is the past they are running away from or the future they are rushing towards. All we know is that, as Leo unconvincingly consoles, “We don’t need to keep talking about this, but we need to keep going.” Tampa is only four to five hours away, he reminds her. So, they get in their car and they drive.

There’s a refreshing visceral pleasure in following Crystal and Leo without knowing where they’re going, because even they don’t have much of a clue about what they’re doing. It’s a marvelous thing to experience—this meta-empathy of confusion and dislocation—but it can only happen once, and I’m not about to starve you of that pleasure if you haven’t already seen it. The overall trajectory of Leo and Crystal’s narrative seems best encapsulated by noir-sleaze master Orrie Hitt in his novel Unfaithful Wives: “They weren’t going any place. Christ, they didn’t have enough money between them to get out of town. They were just a couple of jerks trying to run a dream into overtime.”

Seimetz’s story is something straight out of the vintage noir paperbacks of Harry Whittington, Day Keene, or Gil Brewer—writers who, coincidentally or not, were based in or around St. Petersburg, FL, the hometown of Seimetz and the setting for Sun Don’t Shine. Like those writers before her, Seimetz captures the sweat-stained angst of working class protagonists who lack the means to outrun their past or escape to some future, leaving behind the dreary, sun-drenched rot of the Florida landscape. I don’t know how much of the influence is deliberate or how much is chance—or maybe it’s something in that Florida sunlight—but Seimetz also shares certain stylistic characteristics with those artists. Their narratives alternate between frantic energy and a more anxious lethargy, like a bad panic hangover that just won’t go away. The total effect is a nightmarish haze of paranoia, hysteria, and murder.

Seimetz’s direction suggests an unlikely but complementary fusion of noir and experimental cinema. Think the pulpy mania of Joseph H. Lewis or Anthony Mann mixed with the ethereal, tonal ambiance of James Benning or Terrence Malick. Heightened levels of domestic violence—often exacerbated by the claustrophobic confines of cars or cramped living spaces—alternated with the trance-like repetitiveness of highways and back roads. Nightmare and dreamstate—and nothing in between. Instead of long shots that would establish location and a more complete sense of space, Seimetz prefers medium 2-shots (restricting the world to the two lovers) and extreme close-ups (disembodying them from their surroundings and each other). This insures that Crystal and Leo never feel at home in any space, and that they—like us—are never quite sure where they are.

At the heart of Sun Don’t Shine are two extraordinary actors: Kentucker Audley (Leo) and Kate Lyn Sheil (Crystal). Both are bright up-and-comers in the indie film world. Audley is a fantastic director of naturalistic ensemble dramas (if you haven’t already, go watch Open Five), and Sheil recently appeared in Rick Alverson’s The Comedy and Alex Ross Perry’s The Color Wheel. On-screen together, they project an aching and devastating sense of intimacy. Audler is ruggedly handsome, unshaven and sweaty in a sleeveless tee—there’s an almost classical sense of masculine sensitivity and toughness that recalls James Dean. Sheil delivers a volatile performance composed of expertly caged emotions and deliberate revelations. Part of what makes them so perfect on screen together is that, right off the bat, there’s an immediate sense of history between the two of them, a sense of comfort and knowledge between their bodies about how they fit together, and how they hurt. Their spontaneity belies an implicit practice to their gestures, and it begs the question: how many times has this happened before? The duo is an inspired casting choice, and their performances resonate long after the film is over.

At the heart of Sun Don’t Shine are two extraordinary actors: Kentucker Audley (Leo) and Kate Lyn Sheil (Crystal). Both are bright up-and-comers in the indie film world. Audley is a fantastic director of naturalistic ensemble dramas (if you haven’t already, go watch Open Five), and Sheil recently appeared in Rick Alverson’s The Comedy and Alex Ross Perry’s The Color Wheel. On-screen together, they project an aching and devastating sense of intimacy. Audler is ruggedly handsome, unshaven and sweaty in a sleeveless tee—there’s an almost classical sense of masculine sensitivity and toughness that recalls James Dean. Sheil delivers a volatile performance composed of expertly caged emotions and deliberate revelations. Part of what makes them so perfect on screen together is that, right off the bat, there’s an immediate sense of history between the two of them, a sense of comfort and knowledge between their bodies about how they fit together, and how they hurt. Their spontaneity belies an implicit practice to their gestures, and it begs the question: how many times has this happened before? The duo is an inspired casting choice, and their performances resonate long after the film is over.

Lastly, I’d like to applaud the film’s fantastic crew. Sun Don’t Shine‘s soundscape, designed by Ben Huff, is composed of the barest elements, so that each and every noise—whether a whisper or a scream, a humming refrigerator or a slamming car door—seems explosive. Even the smallest sounds are imbued with nervous energy. It’s a subtle, yet amazingly effective, way of keeping the audience ill-at-ease. Editor David Lowery (himself a distinguished director and—full disclosure/reminder—a sometimes contributor to this site) skillfully oscillates between short, choppy shots and long, uninterrupted takes, the effect of which is an unbalanced sense of time. And then there is the magnificent 16mm photography by Jay Keitel, who perfectly captures the pulpy and lyrical tones of the film. I’m sure I’m missing some key players whose vital role is known only to those on the set, but on the whole, and from every angle, Sun Don’t Shine is just such a finely crafted film.

— Cullen Gallagher

Pingback: THE 2012 HAMMER TO NAIL AWARDS – Hammer to Nail

Pingback: OPEN FIVE 2 – Hammer to Nail

Pingback: A Conversation With Amy Seimetz (SUN DON’T SHINE) – Hammer to Nail

Pingback: THE 2013 HAMMER TO NAIL AWARDS – Hammer to Nail