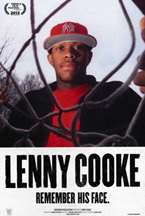

LENNY COOKE

(Lenny Cooke world premiered at the 2013 Tribeca Film Festival. It is currently screening theatrically throughout the country—visit the film’s official website to find out when and where. Also, be sure to read Susanna Locascio’s A Conversation With Josh And Benny Safdie And Adam Shopkorn.)

With a pair of shaggy-dog features and a slew of similarly unpolished shorts under their belts, the brothers Safdie make their documentary debut with Lenny Cooke, a profile of the titular former high school hoops phenom. Their portrait is comprised of footage of Lenny spanning the summer after his junior year (when he ranked among current Knicks Carmelo Anthony and Amar’e Stoudemire as a top incoming senior) to his present state—a bloated bundle of dashed dreams living modestly in Virginia and watching Sportscenter highlights of LeBron James’s ongoing run of b-ball divinity. The Safdies and collaborator/producer Adam Shopkorn have organized and editorialized the images and sounds at their disposal in a self-consciously tragic way, playing up Lenny’s squandered potential while also preserving his humanity and his status as a victim of the fundamentally crooked professional amateur sports complex.

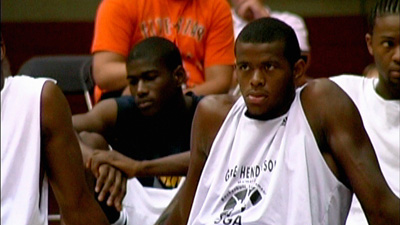

In a sense, Lenny Cooke is a record of Lenny watching his life unfold and, ultimately, pass him by. When we’re first introduced to him, he’s an outrageously talented 18-year-old shooting guard with a non-existent work ethic, recently relocated (following stints at various NYC schools) to Old Tappan, NJ, living under the roof of his new guardian, Debbie Bortner, a teammate’s mother. He gives an ESPN reporter a guided tour of Bushwick, Brooklyn, the neighborhood of his youth, where he tellingly notes that the apartment building he grew up in was also inhabited by a revolving cast of junkies and dealers and fiends and hustlers.

He and his friends snack on McDonald’s fries at Bortner’s house while watching the 2001 NBA Draft, which marked the first time that a high school senior (Kwame Brown, an unmitigated bust) was selected as the #1 overall pick; Lenny vocally lusts after the fame/fortune that seems just around the corner, blind to how those ambitions conflict with his incredulity at an 8:00AM basketball summer camp call-time. Soon enough, Lenny’s career will derail before starting, due in equal measure to a complicated family life, the influence of meddling and money-hungry agents, and the ever-escalating stars of his peers, whose respective successes established expectations so high that the anxiety of trying to meet them surely contributed to his failure to launch.

He and his friends snack on McDonald’s fries at Bortner’s house while watching the 2001 NBA Draft, which marked the first time that a high school senior (Kwame Brown, an unmitigated bust) was selected as the #1 overall pick; Lenny vocally lusts after the fame/fortune that seems just around the corner, blind to how those ambitions conflict with his incredulity at an 8:00AM basketball summer camp call-time. Soon enough, Lenny’s career will derail before starting, due in equal measure to a complicated family life, the influence of meddling and money-hungry agents, and the ever-escalating stars of his peers, whose respective successes established expectations so high that the anxiety of trying to meet them surely contributed to his failure to launch.

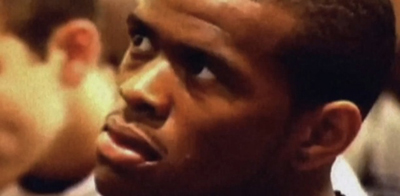

Lenny turns 19 and thus becomes ineligible to play high school basketball. He moves out of Bortner’s and in with an enigmatic employee of a company called “Immortal Sports,” electing to spend his senior year working out and preparing for the 2002 NBA Draft. He winds up going unselected and proceeds to ply his wares across a slew of international and sub-NBA pro-leagues en route to burning out, gaining a bunch of weight and settling down with his disarmingly patient girlfriend Anita in the Old Dominion. The Safdies follow him as he retraces his steps both verbally and physically and throws his own birthday somewhere in the Virginian boondocks (and, most significantly, a world away from the basketball groupies and bottle service he seemed destined for). Their devotion to Lenny manifests itself mostly through their careful documentation of his rants and mutterings, rendered not so much pathetically or sympathetically but rather as the captivating expressions of a man who has been betrayed by everyone—most of all, by himself.

Early in Lenny Cooke, then St. John’s basketball coach Mike Jarvis compares the plight of high school basketball studs contemplating going pro with slavery, his reasoning implicitly being that budding superstars like Lenny mostly hail from super-low-income backgrounds and thereby find themselves at risk of being shamelessly exploited by suit wearing slicksters and down-and-out family members alike. (The NBA changed its rules following the 2005 Draft such that high schoolers are required to be at least 19 years old and one year removed from the completion of their amateur eligibility in order to declare.) What Jarvis’s critique and the Safdies’ film regrettably elides is that the rules as presently configured are every bit as liable to yield Lenny-like figures, a systemic injustice now perpetrated by a gang of unsettlingly faceless entities: the NCAA, state and private universities, television networks, corporate sponsors, shadowy collegiate athletics boosters, etc. But it’s no fault of theirs that the Safdies aren’t polemicists, regardless of how their film seems to invite us to reevaluate the socioeconomics underlying the pro sports dream machine.

Early in Lenny Cooke, then St. John’s basketball coach Mike Jarvis compares the plight of high school basketball studs contemplating going pro with slavery, his reasoning implicitly being that budding superstars like Lenny mostly hail from super-low-income backgrounds and thereby find themselves at risk of being shamelessly exploited by suit wearing slicksters and down-and-out family members alike. (The NBA changed its rules following the 2005 Draft such that high schoolers are required to be at least 19 years old and one year removed from the completion of their amateur eligibility in order to declare.) What Jarvis’s critique and the Safdies’ film regrettably elides is that the rules as presently configured are every bit as liable to yield Lenny-like figures, a systemic injustice now perpetrated by a gang of unsettlingly faceless entities: the NCAA, state and private universities, television networks, corporate sponsors, shadowy collegiate athletics boosters, etc. But it’s no fault of theirs that the Safdies aren’t polemicists, regardless of how their film seems to invite us to reevaluate the socioeconomics underlying the pro sports dream machine.

It’s not so much that the Safdies are concerned with how their subject got screwed by others; rather, they lavish their endearingly indelicate attention upon his sheer screw-up-ness. Lenny ends the film boasting of the heightened maturity of his current perspective on what might have been, and despite our having been presented with little in the way of concrete evidence that he’s right, his claim nevertheless registers as true.

— Dan Sullivan