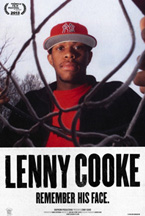

A Conversation With Josh and Benny Safdie and Adam Shopkorn (LENNY COOKE)

(Lenny Cooke opens theatrically on Friday, December 6, 2013. It world premiered in the Viewpoints Section at the 2013 Tribeca Film Festival. Visit the film’s official website to learn more. NOTE: This piece was first published on April 24, 2013.)

(Lenny Cooke opens theatrically on Friday, December 6, 2013. It world premiered in the Viewpoints Section at the 2013 Tribeca Film Festival. Visit the film’s official website to learn more. NOTE: This piece was first published on April 24, 2013.)

In an era bloated with HD content, the films of brothers Josh and Benny Safdie embrace imperfection. They mix actors with non-actors, film with video, realism with fantasy, their roving camerawork creating images dense with texture. But there’s also an emotional density that is hard to explain. There’s something sharp yet compassionate about their stories. I’d hesitate to call it a philosophy, but their films display a great love even for the small, ugly things that make us human, and somehow, seen through their lens, it makes them shine. This sensibility is more evident than ever in their first feature documentary Lenny Cooke.

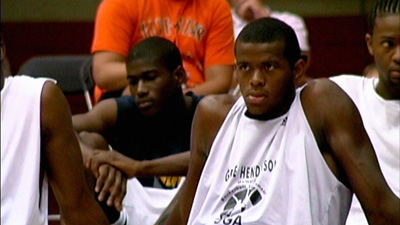

Producer Adam Shopkorn spent years filming rising high school basketball player Lenny Cooke, considered the best in the country until some bad luck and worse decisions dimmed his star. Almost a decade later Adam and the Safdies decided to pick up Lenny’s story, following him to his home in Virginia, a simple life far away from the gilded hype of the NBA that everyone had convinced Lenny was his future. The film evokes larger systemic questions about racism, or the way industries prey on young talent. But at its core is an intimate, at times uncomfortable, dedication to Lenny’s lived experience. Lenny Cooke refuses easy answers, dwelling instead on the classic American question of what happens to a dream deferred.

After the film’s world premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival, I talked with producer Adam Shopkorn and filmmakers Josh and Benny Safdie about reviving Lenny Cooke.

Hammer to Nail: What was the process of Josh and Benny initially getting involved in the film? Did Adam just sort of hand over the hard drive?

Josh Safdie: It was a much bigger conversation. We had just finished Daddy Longlegs, we were doing Q&As and the film was just being released when Adam approached us. I’ve known Adam since I think I was 12 years old.

Adam Shopkorn: Younger. Josh was like 8, Benny was probably like 5.

Benny Safdie: You were at our bar mitzvah. You were holding the chair.

H2N: You went to school together?

AS: No, family friends. I was 5 or 6 years older than them.

AS: No, family friends. I was 5 or 6 years older than them.

JS: I guess I was 17 when Adam was [first] working on this project, and I was just starting to become obsessed with movies, making movies of my own, and I loved basketball very much, so it was always a very intriguing project. But then we kind of fell out of each other’s lives, and then he came to the screening and he said, “Look, can you help me finish the film?” And I didn’t know what that meant, and we didn’t know what would go into that process, because we all know that making movies is extremely difficult, and nobody wants them to exist. So he started to show us footage. I’d say the one clip that convinced us to make the film was the shot that’s in the movie of the girl in Vegas sitting on [Lenny’s] lap. It was that shot that kind of told us that this story is very interesting. I mean the story is interesting on the page, we just didn’t know if we could make it happen.

BS: It was when we saw that there was something in the older footage that we could work with. There was enough under the basketball to really make a true portrait.

H2N: For you it was that moment that spoke to you as filmmakers?

JS: It spoke to us as humans! That was the moment where we were like, “Okay this guy is human,” because all we’d seen up until then was basketball footage.

H2N: Did you watch all of Adam’s footage chronologically straight through?

JS: That’s when we started to watch all of it.

BS: At that point we had to.

JS: And we started doing crazy detective work where we were trying to figure out what happened because [Lenny’s] story is not clichéd at all. It’s a very intricate story of very subtle human error, which plays into the ego, his management of the precarious equation of life. And to this day it’s still a mystery. It’s still a very opaque story, it’s still intriguing to us. The only way we can access it is emotionally, and understanding who Lenny is as a person.

H2N: So Adam showed you all the footage and you all three decided we’re going to move forward. What was the process from there? Did you know right away you were going to have to film with Lenny again?

BS: After looking at the footage we were like, okay, we have to film him, and Adam had to go through the process of getting back in touch with Lenny.

H2N: So you hadn’t spoken with him?

AS: It had been awhile. So I first reacquainted myself with Lenny to make sure that this could actually happen. And that wasn’t the easiest process because by that point he had been burned one too many times. I guess he realized all I wanted to do was finish something that I started. He was the one who was a bit elusive after the 2002 NBA draft, and he fell out of touch with me because he sort of fell in with a different crowd and that crowd wasn’t as receptive to having me around. And after he didn’t get drafted I guess there was a little bit of me that was like, “Oh God, now what do I do?” So a week went by, a month, two months, and then some years, and then all of a sudden it was a project that was sitting there idle while I was reading about Lenny online and in the newspapers. So there was that whole midsection that was missing that we had to go out and find, when Lenny was traveling the world as a journeyman. And we were fortunate enough to track down a lot of the footage that kind of shows you the environment that he was playing basketball in. Which is the polar opposite of the environment of a professional basketball player in the NBA. That arena in Indiana is one of the most well-attended high school gymnasiums in the country. So you can imagine when the high school basketball team plays they fill that place and there are 15,000 people there to see high school kids play, and here Lenny was playing in a professional basketball league and there were 37 people there. It’s really bleak. The further removed you get from the NBA, that’s what it looks like. It’s not glamorous.

AS: It had been awhile. So I first reacquainted myself with Lenny to make sure that this could actually happen. And that wasn’t the easiest process because by that point he had been burned one too many times. I guess he realized all I wanted to do was finish something that I started. He was the one who was a bit elusive after the 2002 NBA draft, and he fell out of touch with me because he sort of fell in with a different crowd and that crowd wasn’t as receptive to having me around. And after he didn’t get drafted I guess there was a little bit of me that was like, “Oh God, now what do I do?” So a week went by, a month, two months, and then some years, and then all of a sudden it was a project that was sitting there idle while I was reading about Lenny online and in the newspapers. So there was that whole midsection that was missing that we had to go out and find, when Lenny was traveling the world as a journeyman. And we were fortunate enough to track down a lot of the footage that kind of shows you the environment that he was playing basketball in. Which is the polar opposite of the environment of a professional basketball player in the NBA. That arena in Indiana is one of the most well-attended high school gymnasiums in the country. So you can imagine when the high school basketball team plays they fill that place and there are 15,000 people there to see high school kids play, and here Lenny was playing in a professional basketball league and there were 37 people there. It’s really bleak. The further removed you get from the NBA, that’s what it looks like. It’s not glamorous.

H2N: from a production standpoint, how did the logistics work? Did you touch base with Lenny first and get to know him or did you just roll the camera?

JS: The first time I met [Lenny] was in New Jersey. And we kind of ran all over the place because he was in his presentation mode… We didn’t include any of it in the movie because it was just too confusing, and I think wrong, because it was his way of trying to present himself to us. He had rented a Jaguar…

BS: He was trying to show off for the camera.

JS: So that phase kind of ended. Basically we knew we were going to get deep into the film when we knew we had to wear that part of him down. The idea of him being this superstar, he had to drop that and start being real with us.

BS: Yeah, it was three years of shooting. And all throughout that we had this past capsule that was unchanging so we could sort of look at that as fiction, it was not going to change. It will help us know what we need to shoot later on, what holes we need to fill in the story.

JS: It’s really like being a detective. We would pull up to the town that Lenny was in, and I would tell Adam, “Just drop me off here and I’ll walk the rest.” We’re talking about neighborhoods where there’s no white people, and I’m walking through the neighborhood and I’m just a stranger, who the hell am I? I became obsessed, we all became obsessed, with trying to get to the real Lenny. Which is what I think the film ultimately does. So I wouldn’t even want the car to pull up so I could just walk into his mother’s house, or walk into his house, and surprise him. And he sometimes would be upset about that, other times he’d be ecstatic about it. And, you know, I would walk in with files and files and files I’ve read, hundreds of hours of watched footage and research on the internet, I knew so much about Lenny. And he started to know stuff about me, because a big part of filming fiction or non-fiction is basically creating a dialogue between you and the subject. Whether it’s a non-actor or it’s a real person you want them to feel comfortable to perform as themselves. And it was lopsided for awhile because I knew so much about Lenny. I think that’s very interesting, it creates a very sensitive perspective. I would just constantly be looking for a reason to fall in love with Lenny. I was always looking to fall in love with Lenny, always. No matter what.

H2N: Would the three of you go together?

BS: That drive was monstrous.

JS: We would go down together to Virginia, but I would be the only one filming.

BS: There was one camera the whole time.

AS: My style is always to intentionally disappear, like what’s the purpose of me being around while Josh is working? We would equip Josh with everything he needed and then send him in to go to work. And Benny would be working.

BS: Yeah, I’d take the drive with me and be editing the footage from the past while we were down there.

AS: It’s exactly what I needed, basically.

JS: And we would reconvene at the end of every day and talk. We literally were like a mobile unit.

H2N: So you were editing as you were shooting as well?

BS: Yeah. And I think what was hard about that was, it was much easier for me to grasp an idea of the older footage because I was able to sit with it, and live with it, and understand its language, and with the newer footage it was always changing.

AS: And we didn’t know if Lenny was putting us on or not. There was no put on from the old stuff. Lenny would arrange these weird things, and these guys would be like, “We don’t have to go do that,” and I’d say, “Well you never know.” But it took a long time to cut through the bullshit in the new stuff because for awhile Lenny believed that this was the Lenny comeback story.

BS: He would create these events that would play to that narrative, and we would keep filming after those events were over. I think there was a really big breakthrough moment where we’re down in Virginia, and all of his friends were like, “Oh, this is ESPN,” all this sports TV, and his fiancée was like, “I think it’s something deeper than that.”

AS: She knew. They said, “This is some ESPN thing,” and she said, “Nope. This is different than ESPN.” She didn’t expound on what she meant.

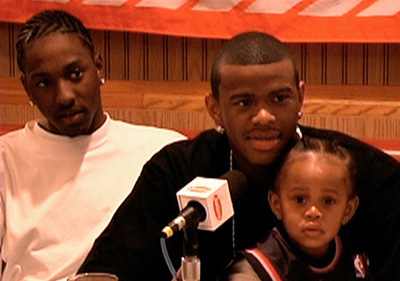

BS: She’s right, you know. In the end we’re creating an individual portrait of Lenny and his decisions. We’re following him from the beginning to the end. You have all these memories [of Lenny] that you normally wouldn’t have. So when you see [him reunite with] Carmelo Anthony on the court, you think, “Why do I know what that feels like? Why do I feel so strange watching it?” And it’s because you’re sitting right next to Lenny watching it. And Lenny watches these players with a completely different perspective. He had the ability to be there, he was better than them.

BS: She’s right, you know. In the end we’re creating an individual portrait of Lenny and his decisions. We’re following him from the beginning to the end. You have all these memories [of Lenny] that you normally wouldn’t have. So when you see [him reunite with] Carmelo Anthony on the court, you think, “Why do I know what that feels like? Why do I feel so strange watching it?” And it’s because you’re sitting right next to Lenny watching it. And Lenny watches these players with a completely different perspective. He had the ability to be there, he was better than them.

JS: Anita, [Lenny’s] fiancée, I remember the time before we went down there for his 30th birthday party, she was watching TV, and I was in the room with her, and we were just hanging out. I was kind of filming her, kind of letting her know what I’m about. She was watching Basketball Wives, it’s a reality show. And she was asking me questions, like, “So is that them? Is that just how they are?” And I was like, “Well, reality TV is a little different, the producers tell them what to do sometimes. Ultimately yes, it is kind of them, but it’s how they want people to perceive them.” And she was like, “Huh. Wait, so the cameras were in the room beforehand?” And she started to understand this idea of filmmaking and what is true and what isn’t true. And I found that to be so interesting, because when I went back to their house after his 30th birthday and she’s cooking the food and stuff like that, I almost feel like I’m watching this performance of hers. I don’t know, I’m very intrigued by that footage.

AS: She’s very bright, she’s very intelligent and she’s very perceptive. I’m Lenny’s number one fan, but I’m also Anita’s number one fan. I think Lenny’s very lucky to have Anita in his life.

H2N: What was Lenny’s reaction when he saw the film? Was he involved while you were editing or did he see it when it was finished?

AS: Josh and I went to pick him up at Penn Station at like quarter after two in the morning and we didn’t tell him that the film had been accepted to Tribeca. So we were wheeling the bags towards the hotel, and Josh goes, “The film’s in Tribeca Film Festival.” And [Lenny] drops his bag, like right in the middle of Penn Station, and he’s like, “You guys are fucking with me, right? Don’t fuck with me Josh, don’t fuck with me Adam. That’s De Niro’s shit, right? The Tribeca shit, that’s De Niro’s shit?” Josh and I were like, “Yeah.” And he’s like, “This is serious shit!”

BS: We had a screening room, and [Lenny] watched it in the screening room with a bunch of his friends, and it was kind of this triumphant moment for him. Afterwards, he was like, “I laughed, I cried.” He just gave us this hug like I’ve never gotten from him, and he said, “Thank you, thank you.” To me that was unbelievable, because it was like, the story’s finished, he can kind of close that part of [his life] now because it’s done. When you make a movie that’s kind of what happens.

JS: [to Adam] Did you tell [Lenny] that I was really nervous to show the movie?

AS: No, I didn’t tell Lenny. But these guys were really, really nervous. For me it was like, I’ve been thinking about this project for so long that just the mere fact that it’s coming to its conclusion, it didn’t make me nervous. And I really sat down and I thought about it, and I went through it from beginning to end in my head, and I was like, You know something? There’s nothing in here that would really embarrass [Lenny].” I thought it was a really accurate portrayal of what happened, and we were really consistent with that. So if he were to be pissed off it would be sort of on him.

H2N: I’m not really a sports fan, I don’t know much about basketball or the NBA, but the documentary was such an experience of a human story as opposed to a sports story of a comeback or a failure, that was really striking to me. In the press notes you mention that you have this idea of the American dream as a concept, and an endgame, could you talk more about that?

BS: Yeah, usually the American dream, you work towards it, but it never happens while you’re just starting to work. When it comes too soon it kind of negates what the American dream is all about. That’s kind of what was hard for me, to go back to when we were going to show [the film to Lenny], is we were really getting into his head and studying his decisions, and that’s going to be hard for anybody to watch, it’s hard for me to watch sometimes. But I think for Lenny it was going to be a like a psychoanalysis, and he’s never really done that.

BS: Yeah, usually the American dream, you work towards it, but it never happens while you’re just starting to work. When it comes too soon it kind of negates what the American dream is all about. That’s kind of what was hard for me, to go back to when we were going to show [the film to Lenny], is we were really getting into his head and studying his decisions, and that’s going to be hard for anybody to watch, it’s hard for me to watch sometimes. But I think for Lenny it was going to be a like a psychoanalysis, and he’s never really done that.

JS: I find it to be so fascinating what has become of the American dream. I think that the generations before us, our parents’ generation or our grandparents’ generation, it was a journey, it took time. To tell the story of the American dream, you know, you told that in your 70s. Lenny, he was like a casualty of that, of what’s happening to the American dream as a concept as opposed to a journey. It means something before it is something, and that was the problem with Lenny.

H2N: There’s a scene at the end, where Lenny goes back to talk to his younger self at basketball camp, that’s something you created in post-production?

BS: It was CGI. How else would we do that?

H2N: When I saw the film, honestly, I thought he was talking to a relative or his son. It’s a moment of magical realism in a film that otherwise is completely realistic, so that’s why it wasn’t my first thought.

BS: It’s edited in the same way that we edited the rest of the film, so it’s really embedded within the narrative. What I like about it is that you could look at it as if [Lenny’s] just talking to somebody else. Are they gonna listen? Is he going to listen to himself? It’s a complete physical impossibility. But if somebody else listens to him, he kind of [achieves] the same thing.

H2N: Has this inspired you to continue making non-fiction films?

AS: I’m going to make one film every thirteen years. I’ll be the Terrence Malick of documentary filmmaking. [They laugh]

AS: I’m going to make one film every thirteen years. I’ll be the Terrence Malick of documentary filmmaking. [They laugh]

BS: I think we approached this as we would approach any other film. Yes, it was a documentary, and there were certain times where I would have these nightmares just because I realized I was editing real people. I would feel that this was going to have consequences. That was strange. But we still approached it as a film, because I think a movie is a movie.

JS: I don’t know if we’re going to make another documentary.

AS: That’d be great for me, I’d be the only guy that ever got Josh and Benny to make a documentary film. [They laugh]

BS: There’s a lot of this film that was strange. We had this trove of amazing footage that Adam had put together, so we had to go through those fifty hours, and then we went and shot more. And it was a long process, it took us three, four years.

JS: A big attraction to the project was our obsession with basketball, and film, they’re very moody mediums. Also the fact that there was this trove of original footage, and we could span someone’s life.

AS: And it was good, or they would have been in and out real quick. I would not have brought them over. I don’t put bad stuff in front of these guys.

H2N: So it was the unique circumstances of this project that convinced you?

JS: Who knows? You never know what the future holds. That’s clearly what the movie has to say. I’ve shot other documentaries before that never came to fruition, really, I was too obsessed with trying to cover it, and be a narrative filmmaker about it. And I watched the 30th birthday scene and I’m very impressed with myself, with my composure to film certain things and hold [those shots], and really just be present with it because I don’t think I would have done that even three years prior because I would have been so obsessed with trying to get [coverage].

JS: Who knows? You never know what the future holds. That’s clearly what the movie has to say. I’ve shot other documentaries before that never came to fruition, really, I was too obsessed with trying to cover it, and be a narrative filmmaker about it. And I watched the 30th birthday scene and I’m very impressed with myself, with my composure to film certain things and hold [those shots], and really just be present with it because I don’t think I would have done that even three years prior because I would have been so obsessed with trying to get [coverage].

AS: I feel I’ve done something special just completing this film with them as a collaboration, but I’d like to think that we have something here that people are really responding positively to. Now the goal is for Lenny to use this film as a pedestal to get back on his feet. Not over the next year, not to have the same shortsightedness he had ten years ago, but this could put him in decent shape if he wants to do it.

JS: I saw a screening of Hoop Dreams with Arthur Agee present, and that was like a year ago.

AS: And he wasn’t the best!

BS: But Lenny was the greatest.

AS: It’s a little easier to listen to Lenny, when he walks into the gym, than the 73-year-old white guy who’s talking to these kids while they’re falling asleep in the bleachers.

H2N: So you see Lenny taking on an educational role?

BS: I think it speaks not only to basketball players but to kids in general. It speaks about what it takes to succeed at anything, and [Lenny] is just an extreme example.

AS: And the fact that Lenny bounced around so much, and fell so behind in school, and he couldn’t catch himself up in time, he didn’t have the option of going to college. He was essentially forced into professional basketball too soon.

H2N: Maybe Lenny will get to build that YMCA in Bushwick after all.

JS: That would be crazy.

AS: If we get Magic Johnson on board as our executive producer, yeah. [They laugh]

— Susanna Locascio

Pingback: LENNY COOKE – Hammer to Nail