THE BOY BEHIND THE DOOR (Review and Interview)

The Boy Behind the Door can best be summarized as Unrelenting. It starts with something horrifying, a boy in a trunk, then flashes back to like two minutes of a nice peaceful day, then throws us back in the trunk again. From that moment, the Justin Powell and David Charbonier directed thriller leads us through one escape attempt after another as two preteens try to evade their captor. As the film races through one showdown after another, the horror of the situation becomes clearer, this singular house surrounded by oil pumpjacks serves as a pleasure pit for pedophiles. The film premiered at the Fantastic Fest celebration this last week, but I had a chance to talk with the dual directors just before its launch.

“We love films that just hit go from the start and you really just don’t stop and it takes you on a ride,” says Justin Powell, “we were actually a little more concerned about having moments of down time, if we’re being honest.”

Powell and Charbonier are lifelong friends, so they write together in a way that allows them to be brutally honest and constantly refining and sharpening their vision. “I think that so much of the writing process is getting notes and giving feedback,” says Powell, “and having the ability to just be able to do that within ourselves before we have to pass it along to someone else to give additional feedback is just invaluable.”

One thing that stand out with the feature is the unity of energy, the tremendous pace and intensity. There is so little room to breathe, that the few times the film stops, it really pulls you in. “We were worried it might feel like a different movie,” laughs Charbonier. While most thriller scripts tend to be ‘dialogue light,’ The Boy Behind the Door presented a different kind of problem for the writers… even though they always intended to be the ones directing it as well. “We try to make it fun to read,” says Powell, “it’s not just big blocks of text, we really break it up and have kind of fun moments where it’s like we try to describe sounds that you’re hearing and what the characters reacting to in just a one word kind of thing, so that the reader feels like they’re really there.”

I asked the team to send me an excerpt from the script, because sometimes I think it is so difficult to imagine, as a new screenwriter, what something like this film might look like on the page. “Most of our scripts, if I’m being honest, are very dialogue light,” says Powell, “we really are firm believers that film is a visual medium, and so we love to tell stories through as little dialogue as possible and really rely on sound design, without dialogue to help tell that story as well.” You can take a glance at a bit of the Boy Behind the Door script here.

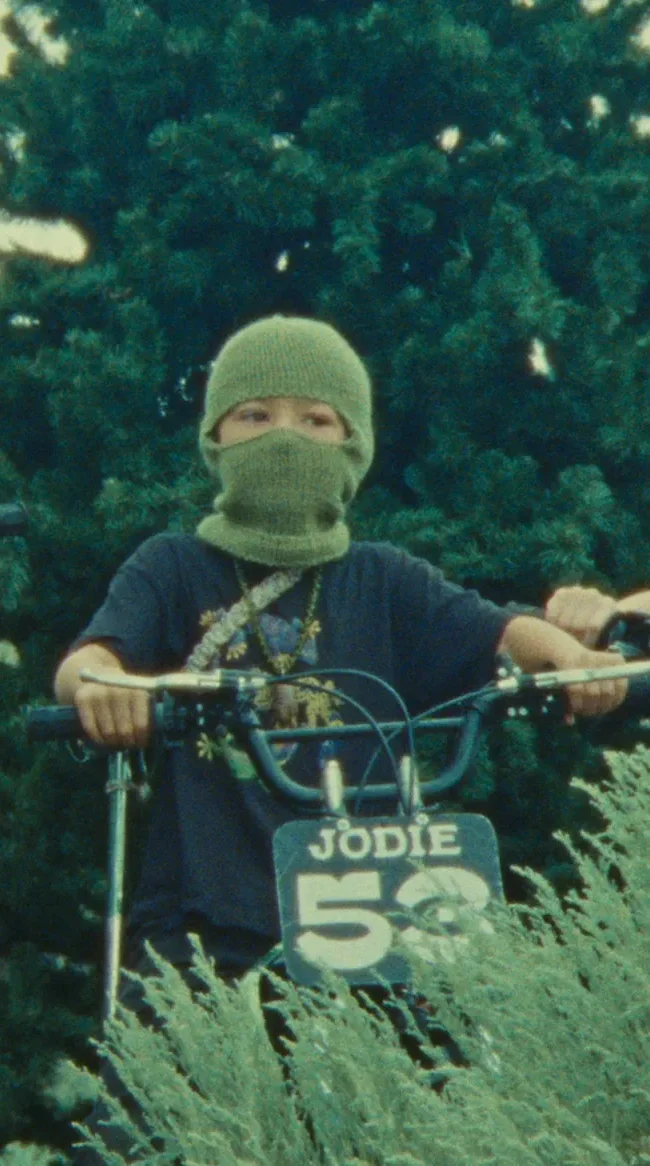

A shot from THE BOY BEHIND THE DOOR

Cinematographer Julián Estrada utilizes shadows and camera movements to give the house its own visual dialogue. There are dark corners where danger lies in wait, and bright white walls in the bathroom, one of the only refuges of safety. “Well, we have a really good relationship with our DP,” says Charbonier, “I really like movies that visually do have a really dark style, like a lot of David Fincher movies. Obviously, Roger Deakins is amazing, you don’t get better than that. So we definitely wanted the movie to feel dark, very grounded, and then obviously there’s a lot of long slowing moving takes. We always wanted the camera to be moving, either if it’s almost unnoticeable or if it’s very intentional.”

Powell agrees that Fincher, particularly Seven, was an influence: “we tried to draw a lot from that with the style a little bit, so I think that it works for the kind of dark creepiness of this story, and so that’s kind of what we landed on.”

Another element that really comes across on screen, and how the camera moves, even its usual height, is that much of the film comes from the perspective of Bobby (Lonnie Chavis), the boy who escapes the trunk and has to rescue his best friend from behind the locked door. We experience a good portion of the film from his POV and are left to figure out the stakes and danger in the same way he does. “I think when we first were initially talking about developing the story, I think we did want to have a story that was really strictly from this one point of view, almost exclusively,” says Charbonier, “I feel like as storytellers, we do really like to identify with one singular character who can really open us into that world and we can sort of follow the world through them and really attach to their fears and their feelings and their motivations.”

“We actually do cut away way more in the movie than originally envisioned,” Powell jumps in, “we got such strong performances from both kids and we were like, ‘We need to also have more Ezra [Dewey, who plays Kevin] in there too, because he’s like, my gosh, he’s awesome too.’”

With two best friends in the film, and two best friends making the movie together, it would be hard not guess that Charbonier and Powell have reflected their friendship a little bit up on the screen. “I think definitely initially that wasn’t the goal,” says Charbonier, “that was, again, something that developed or that came to be as we were developing it. And then I feel we sort of embraced it.” Both Bobby and Kevin have moments of heroism, of terror. In the end, they both save each other in different ways. When one is hurt, the other one helps.

“We had a moment also,” remembers Powell, “David was telling me that like, ‘Oh, I’d totally go back in for you,’ or whatever. I was like, ‘No. I’d actually run like going to get help. I would be useless to you. I wouldn’t be able to go in.’ So we did try and like put ourselves in the situation, and I think that just maybe inherently kind of like, our dynamic does come out a little bit in the characters because of that. But I really distinctly remember David being disappointed about my decision.

Charbonier: “Well the point is, Justin is not as brave as Lonnie.”

Lonny Chavis as Bobby

In fact, Bobby’s decision to go into the house in the first place is one of the strongest moments in the film. He’s a good 100 yards away from the house when he stops and turns back. It’s a difficult moment in any horror film because you have to answer ‘Why would you not just run and try to get help?’ Because the real answer is, if he did, then there’s no film. So from a screenwriter’s perspective, he has to go back to the house. But in the world of the film, the emotional bond brings him back and adds to what I saw as an undercurrent throughout the film, a discussion on masculinity. Any film that opens with one kid tossing a ball over the other’s head (bringing up memories of my own sports incompetence), is going to touch on those issues, if even just in the subtext.

“It is something that we thought about,” says Powell, “we thought about it as coming of age story within the scope of horror thriller, suspense thriller. So yeah, having those moments of decision are like him coming into manhood in a way.” Even as the ball flies over his head, there is the moment where they’re not sure they’re going to go after the ball in the woods. On top of that, there is the wistful fragment of dialogue they share about running away to California. As children they can say things like, ‘Let’s run away and go to California,’ and it’s endearing. Guys don’t say that when they’re 15 or 16. They’re taught not to. That conversation could not happen three years later, unless it’s a very different conversation. “They both have to make these decisions that,” agrees Charbonier, “you’re kind of seeing them have their childhood torn away from them throughout this entire experience.”

By the end of the film, they’ve put aside the childish things. “I know some of the stuff that David’s speaking to,” admits Powell, “like we have even more things that we thought would be strongly emotionally resonant, but after discussions with the team we decided to embrace more of the thriller aspect of it. But I think that it still comes through, and I’m glad that you felt that, because that is something that we thought about.”

Bears Rebecca: Is there a moment that you fought for, like, “I do not want to lose these 30 seconds here just for timing. This has to be in there!”

Justin Powell: Yes. But we lost them.

David Charbonier: Yeah. We actually lost all those bits, so.

Justin Powell: All of them.