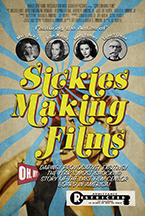

A Conversation with Joe Tropea and Robert A. Emmons Jr. (SICKIES MAKING FILMS)

I met with director Joe Tropea (Hit & Stay) and co-writer/editor Robert A. Emmons Jr. (Diagram for Delinquents) on Friday, May 4, 2018, at the Maryland Film Festival (MdFF), to discuss their fascinating new documentary Sickies Making Films (which I also reviewed), set – as were many of the years I covered at this year’s MdFF – in my hometown of Baltimore. The movie tells the crazy story of the United States’ longest-running film censorship board (1916-1981), located here in Maryland. Tropea and Emmons have put together a concise, well-constructed and entertaining history of the film industry and the forces of repression that have tried to limit its free expression. What follows is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

I met with director Joe Tropea (Hit & Stay) and co-writer/editor Robert A. Emmons Jr. (Diagram for Delinquents) on Friday, May 4, 2018, at the Maryland Film Festival (MdFF), to discuss their fascinating new documentary Sickies Making Films (which I also reviewed), set – as were many of the years I covered at this year’s MdFF – in my hometown of Baltimore. The movie tells the crazy story of the United States’ longest-running film censorship board (1916-1981), located here in Maryland. Tropea and Emmons have put together a concise, well-constructed and entertaining history of the film industry and the forces of repression that have tried to limit its free expression. What follows is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Hammer to Nail: So, gentlemen, rather than starting with my usual first question of “what drew you to your subject,” I’ll ask, instead, about the name of your production company, “Haricot Vert.” Where does that come from?

Joe Tropea: It was a nickname of my beloved dog, whom I actually lost while making this film. She used to have to eat green beans for her diet, so it was natural to call her “green bean,” or “haricot vert,” and that’s where the name comes from.

HtN: What kind of dog was she?

JT: She was a Baltimore pit bull mix, which means she was part pit and part who knows what.

HtN: I’m sure she was lovely. So, your last film, Joe, was Hit & Stay. Did you work on that, as well, Robert?

Robert Emmons: My last film was Diagram for Delinquents, which I directed. It’s another film about censorship, in that case comic-book censorship in the 1940s and 1950s.

HtN: Interesting. So, you were coming to this with a previous film about censorship…

RE: Correct. And then Joe had the idea for the film, and that’s how we linked up in the screening circuits that we were both attending.

HtN: So, Joe, what drew you to this subject?

JT: Following my last film, I wanted a slightly lighter topic than the Vietnam War, and I was aware of Mary Avara, our notorious film censor, here in Baltimore. I was aware of her story and how it intersected with John Waters’ story as a filmmaker, and I just found that a very fascinating topic.

HtN: And indeed it is. You have a lot – a lot – of movie clips in your film, which you need in a film about movie censorship. What were the challenges, if any, of obtaining the rights for those?

JT: Well, I knew that this was going to have to be a clips film, for the most part. I worked for 10 years at a place called Video Americain, which was a beloved rental store, here in Baltimore and the DC area, and I got to watch a lot of movies, as part of my job, and just part of my lifestyle. So, I knew that my background in that was going to be helpful here, and when Bobby – Robert – became a co-writer with me, I knew that I needed help deciding which clip fit which part of the story best. That’s a big part of how he helped me sort the story out. And there’s a lot we could say about fair use…

RE: We took our cue from a lot of films that are based around existing footage, like Los Angeles Plays Itself, films that require and use film clips under fair use. We knew that this film had to be told using movie clips, and we knew that we wanted to try and source as many as we could under fair-use terms, so we went through a pretty lengthy, heavy legal process, by hiring lawyers to look at the film and educate us about things that seemed like fair use and about things that did not seem like they would pass muster.

And so, there was a lot of back and forth in the process about “this seems to be transformative and a critical and historical response,” or “this doesn’t, and seems more narrative-based and you should take this out,” or “you must take this out.” And we’d say, “Well, this is what we’re trying to do,” and then they’d have someone else look at it and say, “You had better take that out, because if it’s legally challenged, it probably won’t pass.” We were fortunate, I think, to have that process, and it was a a lengthy one to decide how we could source stuff to make critical commentary about existing film clips, and not just show them for the nature of showing them.

Our Chris Reed with filmmakers Robert A. Emmons Jr. and Joe Tropea

HtN: Interesting. I really find this film, beyond being just an entertaining documentary about censorship, a really solid history of filmmaking. Could you talk about how you wrote the structure? In particular, you have a lot of on-screen titles for different sections, so you clearly plotted it out in a careful sequence. How did you come by that structure? Were there sections you took out? It’s a really good history.

RE: Thank you! So, this was my first time collaborating with another filmmaker. I’ve always edited all my other films and so it’s been a tremendous process of working with a director and co-writing something. Joe had the idea, told me the idea, and I said, “This is great. You should make this into a movie.” And he had written the first structural outline of the film and had sent that to me. Then, as we made our way through the editing process, Joe would send definite clips that he wanted to use, and tell me how he saw the film, through the interviews. I would take that and start to shape and edit it, and blend it with all the b-roll, and that’s where I started to form all the intertitle names, based on Joe’s early sequence, which had been created in both a thematic and chronological way. I sort of took it and tried to be as clever with the names as I possibly could. If you look at them, most of them reference film in some way.

JT: So, he’s being kind in calling it an outline. Basically, what I sent him was about two-plus years of research, and I work as an historian would: I compile sources and facts and regurgitate them into a large several-page outline. And yeah, I shared that with Bobby, and we kind of decided that it’s a complicated story to tell. The legal cases that we bring up throughout the movie are not just cut and dried. One particular case did not end censorship or change it demonstrably, but it changed an aspect of censorship.

HtN: Is this the 1950s Supreme Court case, or an earlier one?

JT: Really all of them. Other than the very first one – the Mutual Decision, which set the precedent and legal groundwork for censorship – they’re all, after that, just nebulous and difficult to explain. So, we looked at all these chapters and said, “You know, how do we tell this in a way, under 90 minutes, that will make any sense at all?” And it was really great to have someone to help mold the story.

HtN: But this was not your first collaboration, because you co-directed your last film with Skizz Cyzyk.

JT: Yes. So, I’m a public historian by training, and what we do is collaborate with people, and yeah, I worked with Skizz. He didn’t start out being my co-director; he started out just shooting interviews for me, and then we had done so many interviews and I got him so invested in the film that he realized, “OK. I guess I’m a co-director.”

HtN: And though he is not a co-director here, Skizz Cyzyk was your DP [director of photography].

JT: Yes. He shot almost all our interview footage.

HtN: Speaking of which, I wanted to ask you about your choice to shoot your talking heads against a white background.

JT: My quick answer to that is that I’ve seen white backgrounds used in everything from great films to terrible commercials, and what I thought was: “We’re going to be showing a lot of movie clips. They’re going to have a lot of color. We’re going to be talking about a lot of legal things that may sedate people. When we have to cut to talking-head footage, I want it to jolt you awake.” It was also a way of limiting myself and the editor from being able to use too much talking-head footage. So, it was very intentional.

HtN: I mean, they look great! I was just curious, because you don’t always see such white backgrounds.

RE: Yeah, and I had never done that. I’ve used backdrops in some previous films. Joe had mentioned that choice up front and talked about the stark contrast that he had in mind for the interviews, and I had said to him, “I also think it’s a good choice, because I really want to make a documentary where you see talking heads very little.” One documentary that I love is Senna, about the Formula One race-car driver. It’s a beautiful film, and it’s one of the earlier ones where it’s all interview-based, but you never see a single talking head; they’re all just reference by name on the screen. So, I said, “If we can move towards that as much as we can, I think we have enough material here to really build an archival-based film.”

HtN: Were there any people that you sought out, for interviews, who declined to participate in the film? Did you have any trouble getting some people to be on camera? And also, were there people whom you interviewed that you then cut out of the movie?

RE: In the film, I think we used at least a piece of everybody we interviewed, except for Gamse’s husband … the husband of one of the censors, Barbara Gamse. We couldn’t find a spot for him.

HtN: But you put her in at the end, correct?

Norman Mason, Mary Avara, and Rosalyn Shecter. Newly Appointed Censor Board. May 1, 1961. Photo by William LaFoore

RE: Yeah! She’s in there. And he had some things to say, because of his relationship to her, but … you know how these things work. We have great sequences that didn’t make the film; great anecdotes about censoring moments that will ostensibly be on a DVD release, but just couldn’t make it. But I think we used mostly everyone that was interviewed, at least in some capacity, unless I’m forgetting.

JT: And there was only one that we didn’t shoot with the white backdrop, and it’s basically because we had to drive to North Carolina to film the interview. I didn’t have a car at the time, and (turning to Robert) you drove a Fiat, so we really couldn’t put a backdrop in the car with us. We were fortunate that our subject wore all white. It complemented the other scenes, inadvertently. (laughs)

HtN: And so, there was no one that you couldn’t get to be in the film? You don’t have to name names.

JT: (looks at Robert) You’re smiling at me, and I don’t…I’m blanking…

(Robert whispers something to Joe)

JT: Oh! I’m going to tell this story.

RE: It’s a good story!

JT: There was someone I really wanted to include in the film, and that was Melvin Van Peebles. I wrote to him, I got his phone number, I called him up, and I had the most interesting conversation of my life with him. He was down with everything, he loved the idea. I had read his book about his troubles with trying to get his films shown, and everything seemed like it was a go. When I mentioned that we would be driving up to New York to interview him in his home, he was fine with that. I mentioned that I had a very small crew – it would be me and one or two other people, tops – and we were going to bring in some very minimal lights…and he stopped me and said, “You’re not bringing lights into my place.” He didn’t say it that nicely: he used some expletives. But I couldn’t believe that he was down with everything, until I mentioned bringing some lights into his home. That’s where he put his foot down, and that sort of ended that.

HtN: Well, that’s too bad, as I’m sure it would have been fun to hear Melvin Van Peebles’ take on all this.

JT: (laughs) Yeah! I mean, he filmed a love scene with his son, and it was a very controversial moment, and he had great things to say about censorship, but unfortunately we didn’t get to put them in the film.

HtN: So, my final question is about reenactments. You have a sequence of reenactments that all take place around the Senator Theatre. Could you talk about your choice to do that, with a local actor, Greg Golinski playing…

JT: Bill Hewitt, who is a character in the film.

HtN: How did you plan that? Because not everyone wants reenactments in a documentary.

JT: Well, I thought that particular story of Ronald Freeman needed something more to push it over. I knew that the Senator just has a wonderful look to it. We had the Senator stand in for the Rex Theatre, which was really just down the street, but the Rex is really not in any recognizable shape that you could work with. The folks that own the Senator – the Cusack family – have always been very nice to me, in my filmmaking career. I had a friend help with the costumes, and it began to feel like something we could pull off.

With Hit & Stay, we did reenactments, but we shot them all in Super 8, to sort of help sell them. This time, it felt like something worth putting a little more effort into, and I had a friend help with wardrobe, which really helped sell it, we just had fun with it. We filmed some other reenactments, at the Maryland Historical Society, where I work, where we have some rooms that appear to be trapped in time, but the scene that we shot there was too complicated: it ate up 7 minutes of the movie, and ultimately we had to cut it.

RE: I feel like, to me, it’s a very baroque film. It has so much in it, and we sort of pull out all of these documentary stylings. We have some animated sequences, we use all this historical archival material, we have reenactments, and all of this was in an effort to kind of replicate this pseudo … you know, it was a film about film. I wanted it to sort of delve into the excess of Hollywood and filmmaking and include all that stuff.

And I always like things in threes, and so there was a third reenactment that didn’t quite make it in. It was a great sequence as a stand-alone, but as Joe said, it’s very complicated. It’s about one of my favorite films – All Quiet on the Western Front – but it didn’t quite make it into the final edit. And as I said, it was all in an effort create something really rich, and at once real, but also fake, like Hollywood, itself, you know? We sort of give ourselves over to this suspension of disbelief. We know it’s fake, but we’re in it. We wanted the film to have that feeling. That’s why we show you as we do things. It looks like you’re cutting out and pasting the documents, and you’re watching films in the theater with us. It’s all part of this aesthetic real-but-fake kind of experience.

JT: But I generally am against reenactments, not as a hard rule, but they’re very difficult to pull off.

RE: Unless you’re Errol Morris. He pulls it off. Always. (laughs)

HtN: Well, gentlemen, thank you so much! Congratulations on the film. I really enjoyed it.

JT: Thank you, Chris!

RE: Thank you so much!

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)