A Conversation with Nadav Lapid (SYNONYMS)

I met with Israeli director Nadav Lapid (Policeman) on Saturday, September 7, 2019, at the Toronto International Film Festival, to discuss his new film, Synonyms (which I also reviewed), winner of the Golden Bear at this year’s Berlin Film Festival. A bracing exploration of identity across linguistic, national and personal boundaries, the film is loosely based on Lapid’s own experiences as a young man, adrift post-military service in the city of Paris, yearning for freedom from the burdens of history. Here, we follow Yoav (brilliant newcomer Tom Mercier), fresh out of the army, from his arrival in France, through his struggles to forge a new sense of self, to his eventual disillusionment with his adopted homeland. No matter where you go, it seems, there you aren’t. Armed with a thesaurus via which he constantly seeks variations within his French vocabulary, Yoav is really seeking variations of his own, heretofore ill-defined personality. What follows is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Hammer to Nail: Could you start by talking about this movie’s autobiographical roots and how you, yourself, experience something not dissimilar to what your main character, Yoav, experiences in the film?

Hammer to Nail: Could you start by talking about this movie’s autobiographical roots and how you, yourself, experience something not dissimilar to what your main character, Yoav, experiences in the film?

Nadav Lapid: I grew up in a pretty intellectual, artistic, bourgeois family in Tel Aviv, but even in my youth I was reading books about cowboys and King Arthur, and I dreamt about adventure and I started to imagine my military period through the prism of heroic adventures. I looked forward to it with curiosity and trained on the beach in Tel Aviv, running with bags full of stones in order to be in shape for this glorious moment. And like every Israeli, when I was 18 years old, I was drafted and spent 3½ years in the army.

I was a very good soldier because I didn’t understand what it meant to die or to kill. It’s interesting, because in the army you talk about all this stuff, but you don’t understand it at all. What you really don’t understand is that when you die, it’s forever. I mean, you think that it’s a detail in your CV, and not that it’s the last stage in your CV. So, I was a good soldier. The army was super intense but really fun, for me. Then, one day it ends, and you go back to your hometown.

I went back and started to study philosophy at the university and to write short novels, etc., and then one year later I had a kind of…I felt a little like Joan of Arc: I heard this divine voice that called me to leave Israel to save my soul and never come back. Some days later, I landed at Charles de Gaulle airport without any idea of what I was going to do with my life, but determined to stop being Israeli and start being French. That’s the autobiographical background.

HtN: I’m fascinated by this decision – that you have given to Yoav, as well – to stop being Israeli. Why was that so essential?

NL: It was a little like in Rosemary’s Baby: I felt that the devil was living inside me. I felt as someone who lives surrounded by blind people who don’t know they’re blind. I felt like the only seeing person surrounded by blind people; people who don’t see the Israeli sickness; people who are sick but think they are healthy; people who don’t see to what extent all of this is perverse and irrational. There is no cure for this sickness. The only way to cure it is to detach yourself completely from it, to reinvent yourself, to cut yourself off from it in the most brutal way.

I’m not a psychological person, so I won’t say that it was a post-traumatic reaction in a banal way. I mean, today people have post-trauma to the fact that they missed the bus; post-trauma has become such a banality. But I think it was a reaction to all the things I had lived and experienced up until then. I feel that Synonyms is a film about life and existence in the sense that in life, if you grow up in a normal place, everything is okay and then something happens. That’s very general, but I think that Synonyms is about this moment when something happens and suddenly you feel something about whatever you’ve been taught and whatever you were before, and you have to battle yourself.

HtN: Speaking of what the film is about, I want to ask you about the title. It initially seems simple: Yoav is constantly looking up words in French; hence “synonyms.” But it’s also about replacing one country with another and about looking for different meanings in life. Is there anything else that I might be missing?

NL: No, I think you’re right. I mean, we could continue: you might say that Yoav and [his new French friend] Émile are, in a way, synonyms. It’s interesting with synonyms, because the first one, two, three, four synonyms are very close to the original meaning, but the more you continue down the list, it becomes more allegorical. So maybe you can say that Yoav and Emile are distant synonyms. They wear the same clothes, they sleep with the same woman, they use the same stories and they are fascinated the one by the other, but on the other hand they are really different and opposed. Are the “Hatikvah” – the Israelis national anthem – and “La Marseillaise” synonyms? Are all national anthems synonyms? Are all countries terrible and magnetic in the same way, all of them constructed on a kind of dark and violent thing?

HtN: Well, if you buy into the ideology of the nation-state, you are de facto assuming that other people are less than you, whether you’re conscious of that or not.

NL: Yeah, totally.

HtN: And the same thing with religion.

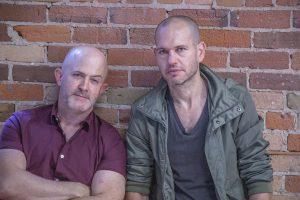

Lead critic Chris Reed and filmmaker Nadav Lapid

NL: The fellow Israelis of Yoav – those who are shown in the movie and those who are not shown in the movie, but believe me, they are the majority – are people who have this very clear vision of distinguishing “us” and “others.” For them, us and the others are antonyms, not synonyms. Us are the Israelis, and the others are … all the others, and on a certain scale they are all, in a way, enemies. And I think that Yoav breaking this dichotomy, this idea of “us” – saying, “I am not a part anymore of this ‘us,’ of this ‘we’” – means he turns this upside down, and suddenly we are the bad ones. But after doing this, he finds himself confronted, at the end, with similarities, with synonyms.

HtN: That’s interesting, but certainly Israelis, and the Jews of this world, have more reason than a lot of people to feel that other people are their enemies. I don’t think that that sentiment is unique, however, though I would argue that, historically, they have good reason to feel that way. Now, I wanted to ask you about the name Yoav. You seem to be particularly attracted to this name; you’ve used it many films. Why do you think that is?

NL: I guess maybe because it rhymes with Nadav. But also, in all my films it’s the same person, at a different age, in a different state of mind, although I’ve been at Q&As where people say the kid from The Kindergarten Teacher grew up to become this Yoav, and I wouldn’t talk about it in such a literal way. I would say that it’s the same sensitivities, same inner conflicts, same things that are nourishing and eating the soul, and it’s only the circumstances that are changing. There’s the same connection to language, to words, same torn soul between fragility and virility, the mind and the body.

HtN: Speaking of Yoav, how did you find Tom Mercier? At first, when I saw the name, I assumed he was French, but no, he’s Israeli. I understand that he learned French for the movie. So, how did you find him?

NL: Tom Mercier was the youth judo champion of Israel, and people predicted that he would have a brilliant Olympic career. He was supposed to bring gold medals to Israel. But one day, he abandoned judo and became a dancer, and afterwards an actor … actually, not really an actor, but he was studying in theater school, where we found him. So, already inside him there was this mixture of something very fragile, sensitive, creative, exposed, and at the same time with a lot of violence that you feel can explode at any moment, which is how I think one feels about him in the movie.

We found him through the normal casting process. But that was the only thing that was normal. He was unbelievable, and what was unbelievable to me about him was the fact that he is a rare combination – and an authentic one – of someone who, on the one hand, is extremely polite and precise, always working hard, and on the other hand he is totally limitless. He is a person who doesn’t know that limits exist. He was just born like this. He is totally ready to do whatever his body permits him to do. And since he is the most physical person I have seen in my life, it’s like having Superman in the cast. If you tell him, “Run 10 kilometers while reciting all the French synonyms to I don’t know what,” he’ll do it. He is able to do everything.

HtN: And certainly your other actors are interesting, as well. How did you find Quentin Dolmaire and Louise Chevillotte?

NL: They are like the opposite case. They are the same age as Tom; they were all 23 years old when we were shooting. I saw Louise in a lead role in a film by Philippe Garrel, Lover for a Day, and Quentin played in a film by Arnaud Desplechin, so each of them had already played one principal role in a movie when I cast them, and in the films of French auteurs whom I totally respect. It’s like in my movie, which has a lot of respect for French cinema, but also enters into a kind of duel with French cinema. So, for me, it was interesting to take these actors and put them in another cinematic dance.

I think what they did in Synonyms was very different from what they had done before. And also, their relationship with Tom Mercier was exactly as it was in the movie, which was fascinating. When we started rehearsing, they were both of them much more experienced, and he didn’t know much about anything. They were much more cultivated; they watched movies. And he was as if were born yesterday. He had no experience, but he had these instincts and this inventive imagination, this huge liberty. And in the beginning, they didn’t know what to do with him; they were amazed but they were afraid.

HtN: He’s like a wild animal.

NL: He’s like a wild animal, but like a wild animal with the soul of a great poet. He’s not just a beautiful beast, though, because he also tells stories and plays with words and is so creative.

HtN: He’s extremely dynamic and really anchors the film. So, congratulations on the film, on your award at Berlin, and thanks for talking to me.

NL: Thanks a lot.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)

Like what you see here on Hammer to Nail? Why not pay just $1.00 per month via Patreon to help keep us going?