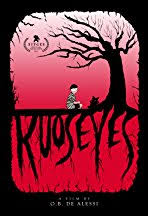

Nick Toti’s “Digital Gods”- Season Two, Transmission Three

(After an intriguing deep dive into the experimental works of fringe filmmaker O.B. De Alessi, our Nick Toti got to have this exciting chat with her…)

(After an intriguing deep dive into the experimental works of fringe filmmaker O.B. De Alessi, our Nick Toti got to have this exciting chat with her…)

Hammer to Nail: Your creative work isn’t limited to filmmaking. I’m interested in the ways these various creative impulses exist in dialogue with one another. For instance, do you see it all as being part of the same expanding lifelong project or does your drawing represent one facet of your personality, your filmmaking another, your writing another, etc.? (Sorry if this question doesn’t make sense. I should have started with something easy like “Where are you from?”)

O.B.De Alessi: The question does make sense but yes, you could have started with something easier!

I think of each project as its own “world” that I create and get to inhabit for a while, sometimes very briefly, sometimes for years. So, in a way, I see my work more as a place that I get to go to, my own private playroom, and I think that reflects in what I do. I guess, seen that way, one could say that my work is both an expanding life-long project and the representation of my personality.

HtN: Let me backtrack now: Where are you from?

OD: I’m from a smallish city in the North of Italy called Alessandria.

HtN: But you currently live in Paris, right? Why did you decide to move there?

OD: Yes, I’ve been living in Paris since 2009. I sort of ended up living here as a result of coming for a short art residency in 2009 and then meeting my now husband. I was living in London back then and, having just graduated, I was looking for something to do next. Through my friend Dennis, I applied for a residency in Paris and was offered a place for three months. Here I met Michael, my husband, who was also staying at the residency. And that’s how it went. We keep talking of possibly moving somewhere else but we can never agree on another place that works for both of us, so we’re still here!

HtN: Do you find that being an expatriate impacts your work? In what ways?

OD: I have been away from Italy, on and off, since I was 19 years old, so pretty much all my artwork has been made as an expatriate. In that sense, I don’t really know what kind of work I would be making if I had stayed in Italy. But it is true that the environment and the people I am surrounded by does completely have an impact on my work. First of all, I use English a lot in my work. It has almost become my first language as I speak English way more than I speak Italian, so it comes naturally to me to think and write in English.

Something else that I believe does affect my work, and that in some way seems to always be an issue when one lives in big European capitals, is physical space, or the lack of it. It doesn’t necessarily have to do with the need to have a big studio, but rather “a room of one’s own.” I find that I can only make a certain kind of work if I’m completely by myself.

HtN: What made you start making movies?

OD: I first started experimenting with filmmaking in 2005, when I was attending art school in Italy. My degree was actually a BA in Painting but, even though I loved painting and drawing, after I bought a video camera I started filming my own performances, which at the time were mostly done in private. I was really excited by the idea of performing in my own films. Working in this medium made a lot of sense to me. I came from an acting background, and what had led me to give up trying to make a career as an actor was that, in the acting world, I felt restricted. Mostly it was because I didn’t like the roles I was given. I was a 19 year old girl, and while I now know that there’s plenty of amazing female roles out there, I felt that the characters I actually wanted to play didn’t exist yet, so I had to create them. I spent my childhood making up stories and role playing them – a very similar process to directing a play (with no audience) or a film (without it being filmed) – and the biggest pleasure I got from doing this was to be able to be characters, which very often happened to be male. That time I spent playing is, I think, the moment of my life in which I’ve felt the freest, the strongest.

Making films, and performing, as an adult, feels a bit like trying to find that space again.

HtN: It’s interesting that you came to filmmaking through acting because your movies are much more “conceptual” than typical Hollywood-type movies. It seems to me that most actors who turn to directing are drawn to more traditional, character-driven stories. Your movies approach character from the inside-out and have very minimal stories (if they have stories at all). Any thoughts on this?

OD: I came to filmmaking through acting and fine art. I was initially drawn to acting but, because of the mixed feelings I had when I started taking acting classes, I decided to apply for art school. So my films are a sum up of my experience as an actor and as a visual artist. For this reason, I am interested in approaching my films conceptually but when I get an idea for a new film, or even for a performance, it’s often a character that first sparks my interest. Much of the performative work I’ve done, while being quite conceptual, is all about the construction of a character and the creation of the character’s story, and I don’t see my films as being so different.

HtN: I’m curious about the way you sign your work: “O.B. De Alessi.” It obfuscates your identity (specifically your gender) and obfuscating identity seems to be a recurring theme in your work. Was this a conscious decision or just my critical brain grasping at straws?

OD: It was a conscious decision and it is very much about obfuscating my identity, specifically my gender identity, but also about creating a new identity for myself. The idea of disguise, of becoming someone else, is something that I’ve always been interested in and something that I’ve always done, often instinctively. Despite it being a conscious choice, it isn’t something I take too seriously. I never intended to create any kind of myth around myself. When I chose this name, it came from the personal need to find a name that corresponds to what I felt I was. The “O” in O.B. stands for Oscar, the name I gave to this sort of alter ego I created for myself (and while I call him an alter ego I also think that he is always a part of me, in some way, even when he is not openly “visible”) while the “B” stands for Benedetta, the name I was given at birth.

HtN: There are a number of what I’d call “totemic” figures or cultural references that recur throughout your work: Michael Jackson, Rimbaud, the notorious Norwegian black metal band Mayhem, etc. Is there something personally significant to these figures or is it just a sort of continuously evolving engagement with whatever catches your interest/imagination in the moment?

OD: There is definitely something personal about the figures I choose to reference in my work. Mostly, they are figures that shaped my childhood in some way. This is the case especially for Michael Jackson and Arthur Rimbaud, but also for Oscar Wilde, Hamlet, Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, Goethe’s Young Werther, Peter Pan and J.K. Huysmans’ Des Esseintes. Oscar, the teenage boy character that was at the centre of a series of projects I worked on for years, basically survived through these figures. Most of what he said or did was a mixture of words and actions coming from either books, films or music. For example, in a photo I took of myself/Oscar, he poses as Michael Jackson but also as Chatterton on his deathbed (as portrayed by Henry Wallis). Michael Jackson was probably my biggest hero as a child, and I made this work shortly after his death. So, in a way, Oscar is my childhood, I guess.

HtN: Who or what else is a conscious influence in your work?

OD: I mostly answered above, but I would say that, apart from the already named references that seem to be recurrent in my work, I usually look for new material depending on what I’m working on. I like to be influenced by absolutely anything. My reading list contains anything from articles about black holes to alchemic elements, to sea monsters, to Russian fairy tales. These days, I also find that real stories are often way more interesting than fiction. I often prefer to watch documentaries over fiction films (although I’m not interested in making one, at least so far) and I always read the news. Reality always seems to be crazier than anything one can imagine.

HtN: One of the things I like most about your movies is the playful nature your work takes with the idea of “authorship.” For instance: Who is the “author” of the Oscar Scar series?

OD: It’s funny, because when I was working on the Oscar Scar blog I felt so deeply involved with the character that I never even questioned the possibility of the blog not having been made by Oscar himself. I mean, I knew that I wasn’t a 16 year old boy when I was writing it (I think?), but to me the blog is Oscar Scar’s. I don’t see it as my blog. Actually, I guess I should mention that, in writing his blog, Oscar Scar was plagiarising Goethe. Each post he wrote is in fact a rewriting of Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther. If you look at the dates of the blog posts they correspond to the dates of each diary entry in Goethe’s novel. So, in truth, Oscar Scar’s blog is not even really his, although he definitely made it his own. At the end of the blog, Oscar Scar announces his death, his last blog post being a link to Schubert’s Death and the Maiden. It was the 23rd of December 2010. That day also marked the end of my work as Oscar (so far, anyway!)

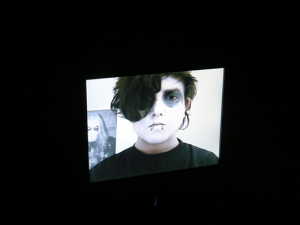

Even if I started using the name much earlier, mostly in writing, I began making work on Oscar in 2008. Oscar was a sixteen year old boy who, initially, lived in the 19th century as a dandy. His life philosophy was to do nothing but think, feel, and dream. This part of his life was mostly recorded through the performance and installation “Oscar” as well as through series of drawings, photos and texts. Just like Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, one day he fell asleep while reading and when he woke up he found himself in a different era, our present. Here, he became an EMO and adopted the name Oscar Scar. His life as Oscar Scar was mostly recorded through his blog, the series of youtube videos The Storms and Longings of Oscar Scar and Oscar Scar’s personal diary. As I’ve said before, Oscar always existed through other characters. It’s difficult to explain what kind of work it is. I could say that it is a very long performance, but then, as I’ve said, I also made zines, the blog, videos, paintings, drawings, installations. Basically, I gave life to a character. I physically became him and at the same time I made work about him.

HtN: The White Moon project is another one that subverts typical cinematic notions of authorship: a movie that exists both on and off the screen whose topic is the idea of a mythical horror movie that (maybe?) doesn’t actually exist.

OD: White Moon is a project I made in 2011, when I was asked to make work for a solo show in London. It originally includes two videos, which were played on a loop during the show, and a live performance which has only taken place once so far. A part of the work was also the “Director’s Notes,” a booklet containing the partial film script as well as notes on the making of the film. This was available for the audience to take during the show. As you said, the main idea is that of a forgotten horror film the director of which is not known, and of which only two scenes and the trailer have been retrieved. The two scenes are the two videos while the trailer is the performance.

After the death of the character Oscar in 2010, I shifted my focus to female characters. For years until then, I had been so focused on the idea of “boyhood” that it felt refreshing to move away from it. I became interested in two stereotypes of women that were created, presumably by men, through literature and later through cinema: that of the so called femme fatale and that of the femme fragile. I chose the characters of Ophelia and Salome to convey the two stereotypes, mostly because they were characters I had loved playing on stage, although the main character of the project is simply called Woman. Since I inhabited the character of Woman and this character is created through female stereotypes, it seemed obvious to separate myself from the role of the director, giving this role to an imaginary person. So, in a way, I was inhabiting two characters, that of Woman but also that of the mysterious director of the film. I made White Moon with this idea in mind. It is not really the kind of film I would make. As much as I was playing with female stereotypes, I was doing the same with stereotypes in the horror genre.

HtN: The House has more of a narrative than your previous movies. Is it fair to see this work as something of a turning point in your filmmaking?

OD: The House is perhaps the first film I’ve made that is more conventionally story driven (by my standards!) so, in that sense, it can be seen as a precursor of Kuo’s Eyes. As it is the case for Kuo’s Eyes, in The House there is no attempt to build layers of fiction around the story or the only character, who is played by me.

The story, which is about a girl who is haunted by her own doll’s house, is very loosely based on an old children’s tale. There was no script as such, and when we shot all I had was a rough storyboard. The shooting and the editing were done very quickly while the building of the props, especially the house, took me weeks (each room is actually painted in different colours, but that ended up not showing because we shot in black and white.)

The House has a narrative, but it’s still very loose and conceptual like much of your earlier work. Kuo’s Eyes, on the other hand, is overtly driven by its narrative. Do you see yourself continuing in this vein or going back to the more overtly DIY feeling of your earlier works?

OD: I see Kuo’s Eyes as a starting point to make more films, keep exploring what this medium has to offer and improve my knowledge of it, but that doesn’t mean that I will stop working with other media. In my case, simpler or cheaper projects do not necessarily mean less DIY (Kuo’s Eyes was definitely one of the most DIY projects I’ve ever worked on). I think it is just about choosing the right medium for the right project.

I decided to make Kuo’s Eyes into a film when I was invited to participate to an exhibition at The Living Art Museum in Reykjavik, Iceland, in 2016. Until then, I had considered making it first into an illustrated book (which I started but never finished), then into a play. The exhibition was called “The Primal Shelter Is The Site For Primal Fears”, and it was about the role of architecture in horror films. I spoke about the idea I had for Kuo’s Eyes with the curators, Maija Rudovska and Patrik Aarnivaara, and they seemed interested, so I took the chance. Making a film, rather than, say, a live performance, seemed the obvious thing to do.

HtN: Did your decision to shoot Kuo’s Eyes entirely in one location stem from this exhibition on architecture in horror?

OD: The decision to shoot the film entirely in one location came as a result of deciding to shoot in the old church, and it wasn’t initially influenced by the theme of the exhibition, though it ended up being very coherent with it. Kuo’s Eyes was made on a very small budget, so part of the reason was practical. The old church, which is only a block away from my parents’ house, was made available to me for free for the entire length of the shoot.

I knew I wanted to shoot the entire film inside a space, including the scenes that take place in “exteriors.” I had taken this decision while writing the screenplay and drawing the storyboard and it was, perhaps, influenced by the fact that I had initially conceived Kuo’s Eyes as a theatre play. When I was location scouting, I was mostly looking for affordable locations where I would have enough space to shoot exterior scenes such has the ones in the woods. I wasn’t very interested in the way the spaces themselves looked, as I was planning to transform them completely anyway. But when I saw the church, I realiszd it was a space that was versatile enough to allow me to shoot all the scenes in it. It was only once I started working in the actual space that I decided to use, rather than hide, the structure itself as part of the the film. I used the texture of the walls to create a sort of abstract landscape in the scenes where Kuo arrives to the woods, for example, and I used smaller rooms within the church to shoot the scenes in Kuo’s aunt’s house. It was also only after Michael (Salerno, who worked as director of photography) and I started shooting that we decided not to limit the shots to the sets but to film around the sets as well. For some reasons, we discovered that by “breaking the spell” we were obtaining the reverse effect of making the film more believable.

There is absolutely no meaning or symbolism implied in the choice of an old church, although I am aware that viewers could think there is, which is also fine.

HtN: Kuo’s Eyes looks considerably more expensive than everything else you’ve made. How did you finance this bigger project?

OD:Most of my work is made very cheaply, but Kuo’s Eyes was slightly more expensive, despite the fact that I managed to cut a lot of the costs by shooting in my hometown in Italy. I paid for most of the production myself, but I was lucky to have contributions from Kiddiepunk and also from my family (who also helped to physically build the set). For the rest, I own an apartment in London which I rent out and which is my main source of income at the moment.

HtN: What are you working on next?

OD: I am working on a new film project, which is still in the very early stages so I don’t really want to say much (or anything) about it. I’m also editing a long-term writing project, and working on a series of drawings which I started a few months ago and sort of abandoned, but really want to finish. Oh, and I’m also taking care of a 13-month-old toddler full time!

For more on O.B. De Alessi, visit her website.

If there are works, dear reader, that should be considered for the Digital Gods column, please share them. If you are a filmmaker/video artist/animator/whatever else whose idiosyncratic/radical/mystical/mind-fucking/ degenerate/unprogrammable/uncategorizable work, please introduce yourself. The call for new work is always open at:

– Nick Toti(@NickTotiis)