A Conversation with Charlène Favier (SLALOM)

I met, via Zoom, with French director Charlène Favier on the day before her movie Slalom (which I also reviewed) opened in the United States. A coming-of-age tale set in the world of competitive skiing that is also a stark examination of sexual abuse between coach and athlete, the movie pulls no cinematic punches in its often disturbing narrative. Actors Noée Abita and Jérémie Renier both deliver wrenching performances, holding nothing back as they plunge us deep into the harmful and uneasy pas de deux. Loosely based on experiences that Favier, herself, witnessed when she was a young skier, the film is both timeless and very much of our time. Please note that the interview was conducted in French and then translated by yours truly. Any errors in the representation of Charlène Favier’s thoughts and words are my own, and mine alone.

Hammer to Nail: I know that you grew up in the resort town of Val d’Isère, as part of the skiing community, but at the same time, the film is not autobiographical. Where did the idea for the film come from?

Charlène Favier: That’s always a complicated question to answer. I started work on the film when I started a writing program at La Fémis, a film school in Paris, and the goal was to write a feature film. I had, in me, many stories that I had already told in short films, and each time they approached a kind of autofiction, in that I revisited a part of my childhood, adolescence and young adulthood, since I’ve lived a somewhat chaotic life. I’ve spent time in Australia, in New Zealand; I’ve had some “deep” experiences, in a manner of speaking, and I feel like every time, these films helped me to understand who I was and to understand what was so strange in my little existence. At the same time, I felt that my experiences were pretty universal, and that is what made me want to make films.

And so, when I found myself in the writing workshop at La Fémis, I kept coming back to this same recurring character of a young woman in the midst of an identity crisis, vulnerable but also a fighter, who took risks and felt certain desires and compulsions. I had already developed her over the course of my short films. And then, in a flash, I came up with the idea of taking this main character, who was also me, in a way, and placing her in the locale I had grown up in, Val d’Isère, as well as in that world of ski. I had, myself, competed, not at the highest level, but at a high-enough level, and I knew that world fairly well and experienced my own controlling relationships with coaches.

It was something I had internalized. I didn’t show up at La Fémis saying, “I’m going to make a film about sexual abuse in the competitive sports world.” Not at all! I just started writing with this same protagonist, who was me, and I placed her in the context of Val d’Isère, and then all of a sudden, I started going through a sort of therapy through this process. It got away from me without me yet understanding what exactly I was writing. Ultimately, it was the people around me – my classmates, my professors, and then my producers – who told me that, beyond everything else I was writing about, I was in effect tackling sexual abuse in the sports world.

At that point, I considered stopping. That’s not what I wanted to do. But then I understood that, yes, this was the heart of the matter. And so I combined that which I had experienced with what I was in the middle of writing, and threw myself completely into the story. Overall, it was a five-year process: I started in 2014 and shot in 2019. In that time, I did a lot of work on myself, evolved a good deal. It helped me a lot to write the film. I had always wanted to write something that would be for the collective good and not just an ego trip. I think cinema should open new doors and horizons for society, for humanity. As a result, I really dove deep into the making of this story.

HtN: Let’s talk about the casting. Obviously, Jérémie Renier has been acting in films for quite a while, but how did you land on him and how did you find Noée Abita?

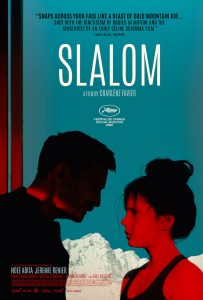

A still from SLALOM

CF: As far as Jérémie goes, I’ve known him, as an actor, for quite some time now; he has a very extensive and varied filmography. I’ve always loved him as a performer because I feel like he has this method-actor quality in his approach to roles, like American actors, in that he transforms himself, physically, entering completely into his characters. For me, that is very important. I, myself, studied at the School of Physical Theatre in London, which bases its methodology on the teachings of Jacques LeCoq and is a school for mimes where one works a lot with body movement, and I think those lessons have stayed with me.

So, I tend to be attracted to actors with a physical approach to their performances, and I immediately sensed such qualities in Jérémie. I offered him the role and he accepted it right away. What followed was a wonderful experience of friendship. We are quite similar, he and I, as it turns out. We both have an instinctive approach to cinema, we’re both extremely active, we’re both just big kids, though at the same time we can be very serious. We’re born just a day apart, though not in the same year. We’re basically the same person. (laughs)

And as far as Noée goes, I saw her for the first time in Ava, at Cannes in 2017, and I right away saw qualities in her that were necessary for the character of Lyz: a young woman, a little of both girl and woman, who has both strength and fragility. Noée has those characteristics, and like both Jérémie and me, she has an instinctive approach to work. None of us intellectualized our movie; I didn’t say, “Oh, I’m going to make a film about sexual abuse in the sports world.” No. It just came out of me. In the same way, Noée, when she acts, it just comes out of her; same thing for Jérémie. We’re like three animals of the same species.

I asked Noée to act in a short film I made in 2018, entitled Odol Gorri, and it was like a preparatory workshop for the feature. We became like two sisters during the production. I immediately felt like Noée understood exactly what I was trying to do. Noée is very mature and is wonderfully sensitive, and working with her on Odol Gorri reassured me that she could do the work. She fights hard for the truth of the performance.

HtN: And even though she is now 22, we believe her as an adolescent, however disturbing that is, in Slalom. Speaking of how disturbing parts of your film are, how did you navigate the more intimate scenes? Especially the one where they have sex? It’s hard to watch, but it must have been hard to film, too. Not only for the actors, but for the cameraperson, Yann Maritaud, as well.

CF: It wasn’t actually complicated at all. It was quite simple and very quick. For many reasons. The first is that Noée and I had already done a similar scene in Odol Gorri, and so we already had confidence the one in the other. Secondly, Jérémie is a very pragmatic actor, who just approached the scene in a practical way, very much at ease, and very reassuring to both Noée and me. Finally, Yann Maritaud, my cinematographer, is my best friend and we have been working together for 10 years. He shot all of my short films; we did 6 before making Slalom. And with the whole team that is behind him – lighting, grip/electric, makeup – we are like one big family, since we’ve all been working together for 10 years. We all know each other so well and, on set, it’s like we are in a cocoon. There is no voyeurism, people make themselves scarce at the right moment. And so that helps with the actors, too, in such intimate moments.

With these sex scenes, then, which I learned how to do in the making of these two films, Odol Gorri and Slalom … and I was terrified on Odol Gorri, though by Slalom I had a handle on them…I understood that in order to film sex scenes, you don’t have to show sex. And everyone says that these scenes are hard to watch, and yet there is no sex: we see very little nudity, we don’t even see any breast, we maybe see a little bit of thigh; we’re mostly on the faces. And so then we just edited together the bare minimum of what we needed, which was 4 shots, showing the least amount as possible. And so with just those 4 shots, it was very simple, and took us just about 30 minutes. It helped that Yann and I know each other so well and that Noée and Jérémie knew what they were doing, so we were very efficient.

Throughout the film, I had a sort of central rule, a kind of dogma; I like working under constraints. And the rule was that everything should be seen from Lyz’s point of view. And so all the shots are motivated by Lyz’s emotional point of view. Anything that is not from that point of view is not in the movie. Except for one shot … I’m not sure if you noticed it or not … which is not from that point of view, and that just happens to come immediately after the rape, when we see Jérémie, his eyes red, his face guilty, he’s almost crying, and there Lyz has actually left the scene, already. That is the only shot in the movie that is not from her point of view, but I felt like it was important to have it because I wanted to humanize his character. Even in that moment, I don’t think even Lyz sees him as a monster; she hasn’t yet come to the conclusion that she was abused. But everything else … in fact, to be honest, I kind of filmed the sex scenes as I did the ski scenes: from the emotional, at times sensational, point of view of Lyz.

HtN: Indeed, you humanize him, and that fact actually renders what he does even more monstrous, because we understand how human it is, unfortunately, to do such things. So, I was struck by the similarities between the opening scene’s heavy breathing and blurry body parts as the girls exercise and the sexual encounter in the gym. Did that evolve in the editing or did you always plan to foreshadow the one with the other?

CF: That was there from the beginning. That breathing is actually very important throughout the film. People often ask me how I filmed the ski scenes, and if they work it’s partly because we did a lot of post-production work on the sound design, including the breathing we hear, which puts us inside of Lyz’s point of view. So that breathing is important in the ski scenes, it’s important in the sex scenes, and it’s important in the opening, as you pointed out. Often, the coach will say things like, “Breathe,” to help the athletes gather their rhythm. And from there we have parallels with suffering, desire, disgust, and all that.

And so there is definitely something sexual, even in the first scene, where she moves her knees around, and then we suddenly have Fred watching the active bodies, and Lyz breathing out as she moves, and I think that is almost sexual. And later, when she is exercising her knee in front of the mirror, that, too, is sexual. When she puts the electrodes on her thighs, making them jiggle, there, too, is something sexual. And what I wanted to show is that, in the sports world, it is very easy to move towards sexuality of the body, because the body is constantly on display, like a performance object, and it can very quickly become an object of desire. There are almost no boundaries; we are offered up to the gaze of others.

I think that’s why there are so many abuses in the world of sports, because people forget the moral codes of behavior; there are no rules, it seems. Normally, when you go to school, you don’t go half-naked; you’ve got clothes on. But here, you go to your training sessions half-naked. And then people lift weights, etc., do other kinds of exercises, and then go have sex in the shower. Why not? It’s all the same … It kind of works like that, I think.

HtN: And certainly there is that incredibly casual way that Fred just asks Lyz to take off her clothes in his office so he can weigh her and take her various measurements. And it’s more than a little shocking, because she is only 15, and he is an adult.

CF: Exactly.

HtN: Speaking, earlier, of how you work with the camera, I was indeed also impressed with how you filmed those ski scenes. It’s like we’re in a James Bond film! (laughs) They’re so well shot. How did you do those?

CF: These, too, were very simple. Just like with the sex scenes. They’re both the easiest scenes to film. (laughs) For the ski scenes, in any case, we didn’t have any real budget or time to do them. Plus, since I wanted them to be seen as if from Lyz’s perspective, I didn’t want these amazing scenes straight out of Eurosport or World Cup skiing, but rather much more organic images. And so I said to myself that the only way to do this would be to glue oneself to the skier in the descent and have these chaotic, but vibrant, moments. Because when one skis, and I am a skier, the body moves, the knees jump, and that is what I wanted to film.

And so I had another cinematographer – not Yann Maritaud – who is an ex-professional skier, who follows Lyz with the camera, at top speed, sometimes in reverse. And he would tell me, “You know, I’m going to do what I can, but the camera will shake, move in all directions.” And I said, “No big deal. That’s even better. I want it to move. I want there to be mistakes.” And he did great work. We owe those ski scenes to his talent, skiing right alongside Lyz.

HtN: And what’s his name?

CF: He goes by his nickname, “Bullit,” but his name is Yann André.

HtN: (laughs) So you had two Yanns on camera, then!

CF: (laughs) Yes!

HtN: Finally, I really loved the music in the film. Often, I find that soundtracks can overwhelm the story, but not here. It was just right. The music underlined the emotions without overdoing it. How did you work with the three credited composers, Alexandre Lier, Sylvain Ohrel and Nicolas Weil?

CF: They are a collective, LoW Entertainment, and they work as a team. It took a while to find the right tone for the movie. I wanted something classic, but not too classic, maybe with the sounds of an electric guitar, or with the feel of the 1970s or 1980s. I love, for example, the soundtrack of Midnight Express; I love Pink Floyd; I love the Velvet Underground. I wanted the score to therefore have some of that influence. So, we tried to mix some piano, violin, electric guitar, to be both neutral and involving. In short, it wasn’t easy.

And sometimes these three would work together, and at other times they would realize that they were creatively blocked and would each go off on their own, coming up with individual ideas. Then, once that produced something that we kind of liked, they would come back together. So, it was a creative back and forth. And what was interesting was that each individual would bring their own particular touch into a collective endeavor. It’s like writing a screenplay as a team: it’s more interesting, because you have more than one mind coming together.

HtN: Well, I admired their work, just as I admired yours. Thanks for making the film, and I wish you all good things with it.

CF: Thank you!

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)

Scott Lerner

Thank you! An illuminating interview about a superb film.