A Conversation with Helen Hood Scheer & Kristy Guevara-Flanagan

The documentary Body Parts is an insightful, hard-hitting exposé of the damage done by the male gaze, whether it be the way it treats women on screen or affects their self-image off screen. It premiered at the 2022 Tribeca Film Festival. where I reviewed it (I also put it on my list of best films of the year). Directed by Kristy Guevara-Flanagan and produced by Helen Hood Scheer, the movie features a varied collection of interviews and archival footage, all of which help to make the case for needed industry change. Body Parts is finally getting both a theatrical and VOD release starting February 3, and I was able to chat via Zoom with both the director and producer last week. Here is a transcription of that conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Hammer to Nail: How did the two of you meet?

Helen Hood Scheer: We met teaching at Diablo Valley Community College in Northern California. We taught the same classes and shared a lot of materials, and then we both got jobs in Los Angeles at the same time. We both moved down here, me to Cal State Long Beach and Kristy to UCLA. When Kristy’s film What Happened to Her was screening in San Francisco—and by that time we were friends, not just colleagues, but friends—I flew up to see her film and afterwards, in her Q&A, she talked about what she wanted to do next, and I told her I wanted to produce her next film, and that’s how it happened. We’ve been friends and colleagues for more than 10 years now.

Kristy Guevara-Flanagan: It was serendipitous that we both got jobs in Los Angeles and moved to Los Angeles at the exact same time. What Happened to Her was also a film about representation of women in film and television. It’s a short film that looks at images of dead women in film and television, pulling entirely from what we call the Hollywood archives, clips from film and TV. With that, I paired an interview with one actress who played a dead body. I thought that there was something really compelling about being able to see these images but also peel back the veil behind the making of the film itself and what goes into it from an actor’s perspective.

With Helen, we originally thought we were going to make a triptych about death, which I had just made, and then sex and then birth and labor on screen, as well. But sex quickly snowballed. There were so many issues and people involved and concerns and high stakes, and we wanted it to really have a collective feel so that you were hearing from all the different people involved in this process, as well as actors at different levels of their career and status.

HtN: This film covers quite a lot of topics, some serious, some fun. I did not know what a merkin was. How much of the material that you cover in the film was known to you, and how much were you surprised to discover as you made it? Beyond the merkin, I was surprised to discover that it was Emily Meade, in HBO’s The Deuce, who was leading the way in requesting intimacy coordinators.

HHS: Can I pipe in for one small correction on that last statement?

HtN: Sure.

HHS: In terms of public-facing actresses, Emily Meade was definitely leading the way in that, but she was inspired by some lesser-known actresses, and I just think it’s an important point to make. There were five actresses who came forward with their charges against James Franco, and Emily Meade was aware of that. Those actresses are ones who had no power, really. Emily Meade felt like she wanted to be supportive of what they were doing and what they were saying. For that reason, she helped to foster this conversation and then those other actresses got left behind. Emily Meade gets a lot of credit, and she deserves a lot of credit. She did something really special, but I just also want to give accolades to people like Sarah Tither-Kaplan, who’s in our film, who had no power and did a lot of the really courageous work, too.

HHS: In terms of public-facing actresses, Emily Meade was definitely leading the way in that, but she was inspired by some lesser-known actresses, and I just think it’s an important point to make. There were five actresses who came forward with their charges against James Franco, and Emily Meade was aware of that. Those actresses are ones who had no power, really. Emily Meade felt like she wanted to be supportive of what they were doing and what they were saying. For that reason, she helped to foster this conversation and then those other actresses got left behind. Emily Meade gets a lot of credit, and she deserves a lot of credit. She did something really special, but I just also want to give accolades to people like Sarah Tither-Kaplan, who’s in our film, who had no power and did a lot of the really courageous work, too.

HtN: Thank you for that correction.

KG-F: As far as any surprises for us, our film took five years to make. We had the advantage of following the news cycle and things that were developing, and we took advantage of that. We started this film before the Harvey Weinstein scandal and The New York Times article and New Yorker article broke and then “Time’s Up” and “MeToo” evolved within the industry and we were following that all along the way. We didn’t know any of that, of course, going in, but the whole film itself was highly researched. I’d say we didn’t know a lot about what goes on in the making of scenes in Hollywood because we’re not from that. We’re documentarians and didn’t know a lot about body doubles, didn’t know a lot about merkins, though I’d heard of them. It was just really research driven to inform us on what goes into it and to talk to people and hear from their perspective, which we also didn’t know. What is it like to be asked to take your clothes off? Or what is it like to do a simulated sex scene?

HHS: And then it inspired a lot of new watching and inspired some repeat watching of films we knew. It was a lot of consuming media and reading histories. We weren’t film scholars, either. We really come as documentary filmmakers with a lot of vérité background and working with archives.

HtN: Speaking of these conversations that you were having with people as part of your research, and assembling interview subjects, were there any interviews, whether from scholars, historians, filmmakers, actresses or others, that proved hard to arrange, whether because of scheduling or just for other reasons? You’ve got great people, like Nicholas Hall and Linda Williams, and filmmakers like David Simon, and actors like Rosanna Arquette and Emily Meade.

HHS: It was very challenging to get through the gatekeepers of agents and managers and publicists and there’s a long list of people that we weren’t able to get in the film. We won’t name names. I think that some people are still quite afraid of repercussions for participating, for speaking up. Also, some people don’t want to draw attention to their older films where they might have performed in less clothes or in roles that they didn’t feel good about or doing scenes that they didn’t feel good about. A lot of people don’t want to draw attention back to older works. I think initially, we really hoped that we would have a lot more celebrities in the film. When we got Jane Fonda, we thought that would open up the floodgates and make everything really easy.

That wasn’t the case. It was still very, very challenging, and lesser-known actors became a bigger part of the film. Technicians were always part of the idea that would be interwoven into the fabric of the film. But it became a real advantage, a real asset of the film, that we have a lot of people who don’t have access to the machinations of power. Celebrities have the ability to speak to The New Yorker, to the other popular publications, The New York Times, to other publications. We really were able to give more voice to the voiceless. It was a challenge that ultimately became one of the treats and surprises of the film to really hear about the experiences of people who don’t have a whole team of people to protect them and ensure their safety.

HtN: As a viewer, I did not feel the lack of big celebrities. You front load with Jane Fonda. She makes an appearance and that’s great because not only is she a big name, but she also has this history, because she’s in her eighties now. You go back and so that’s great. You get that history and then you have enough.

A still from BODY PARTS

HHS: And a great range of writers, like Tanya Saracho and Angela Robinson and Karyn Kusama. There’s a lot of people who are creating the stories that we consume, but don’t always get the limelight.

HtN: Right. Joey Soloway, as well, and then Alexandra Billings. You’ve got great people. So, your film presents some traumatic subject matter alongside other facts that are less so that are just fun. Again, the merkin. It has in many places this jaunty feel alongside the more serious material. I’m just wondering how you navigated this narrative challenge of balancing fun and whimsy with serious and gravitas, which I clearly felt worked.

KG-V: Well, the whole film was a difficult balancing act. Beyond what you’re speaking to, we also have sections that are these going-back-in-time, historical looks at film and television, personal stories, stories in which the cast are really speaking to each other about a singular process or event. It was constantly massaging that, as well as this emotional up-and-down experience for the audience.

HHS: And also not showing the body …

KG-F: As well as not re-exploiting bodies, because we were talking about their experiences of exploitation, often. I want to acknowledge our two great editors, Liz Kaar and Anne Alvergue. It took a long edit. Really, the balancing act was always a part of it, of figuring out that feel, and things were moving around till the very end in order to just hit those right notes. We also rely on our great community of filmmakers and film scholars and friends and family to share the film withand figure out when it’s too much, when it’s too difficult to watch, and ways in which we can lead audiences to some of the more horrific moments which happen later in the film.

HHS: And then there’s also the balance with the clips of both having people be able to focus on what’s said and not just fall into the clips or the scenes of the movie.

HtN: You cover so much ground, yet your film is only 86 minutes long, which is a good thing; I like tight documentaries. That doesn’t mean that all long documentaries are bad, not at all. But what stories or material did you not include that you could have? Because that’s a tight 86 minutes.

KG-F: Well, there is a bit. There were hard things to let go of, that we’re actually trying to maybe bring back in our educational Impact Campaign, such as one historical section about femme fatales that is just an important part of sex on screen. Both looking at it from the early iteration in the ‘40s to the neo-femme fatale era of the ‘80s with Fatal Attraction and Basic Instinct.

HtN: So, you’ve got this Impact Campaign, #moretotalkabout. What are your plans for that? What do you hope to do and what events do you have, if any, as part of that coming up?

A still from BODY PARTS

HHS: We’re working on the Impact Campaign with Level Forward, which is a company that is really trying to walk the walk in changing the way business is done. Our Impact Campaign is in the nascent stages right now, so it’s too soon to say very much about it. We will be doing a variety of different events and outreach campaigns across different industries, to try to not really make the issues that are explored in the film center just around the entertainment industry but also find parallels in other workplaces and aspects of life. We’ll also be doing a lot to try to help schools come up with policies or for their own filmmaking that could help train students better on intimacy practices. There are about 10 different points that we’re going to be doing that it’s a little bit too soon to talk about, not because I’m being secretive, but because there’s a lot that’s also still being developed.

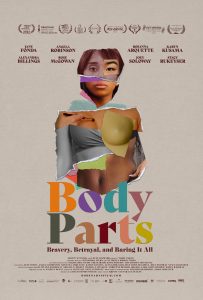

HtN: Fair enough. I really like your poster and its collage motif. Who designed it?

KG-F: The amazing Yen Tan of …

HHS: Otto is the One.

KG-F: I’ve worked with him before. He’s based out of Austin. He’s brilliant and it’s like working with a composer. It’s not like you just hand it over and they’re done. They’re nailing it down and figuring it out. I think that we tried a few different things and it’s hard to represent a film like this in one image. Diversity and plurality of voices is so intrinsic to the story. That was an important thing to capture visually.

HHS: Plus, there was so much we couldn’t use in the poster. It’s a film that’s based on Fair Use, or centers on Fair Use, and the laws around Fair Use are really different for the actual film and for the promotion of a film. Once it becomes something that’s promoting the film or advertising the film, you can’t claim Fair Use in the same way.

HtN: That’s really fascinating. I didn’t realize that. Thank you so much, Helen and Kristy.

KG-F: Thank you. Bye-bye!

HHS: Take care.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)