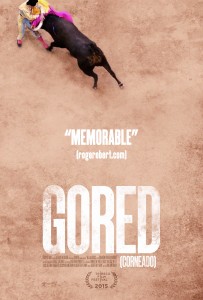

Beautifying the Beast: A Conversation With Ido Mizrahy (GORED)

Ido Mizrahy’s controversial documentary Gored, on bullfighting legend Antonio Barrera, sparked many a great post-screening Q&A at film festivals throughout the world. Gored is available on Amazon (Blu-ray and DVD), Amazon Instant, iTunes and Vudu now!)

Ido Mizrahy’s controversial documentary Gored, on bullfighting legend Antonio Barrera, sparked many a great post-screening Q&A at film festivals throughout the world. Gored is available on Amazon (Blu-ray and DVD), Amazon Instant, iTunes and Vudu now!)

I first became aware of “Gored,”Ido Mizrahy’s complicated portrait of Antonio Barrera, a.k.a. “the most gored bullfighter in history,” at last year’s Tribeca Film Festival. Premiering in the ESPN Sports Film Festival section, the stunningly shot doc – complete with heart-pounding close-ups from inside the ring – follows Barrera as he prepares for his (conflicted) retirement. Which entails the passionate matador not only giving up a life devoted to facing death, but of also laying his dreams of greatness to final rest.

I was fortunate enough to speak with the philosophical Mizrahy a few days after “Gored” hit Netflix (and Amazon and iTunes).

Lauren Wissot (HtN): Can you discuss the genesis of the doc? I believe it all started with your writing/producing partner following Antonio around Spain for a print article, which led to a short film, which eventually led to “Gored.” What convinced you that this story needed to be a feature?

Ido Mizrahy: Yes, my writing/producing partner, Geoff Gray, who had written a feature article about Antonio Barrera for Sports Illustrated a few years ago, jumpstarted this project. They had stayed in touch after the article was published, and at some point Antonio told Geoff he was thinking about retirement. So Geoff approached me about making a short film about it. We figured it would be dramatic and powerful as a short (if not downright brutal). But once I met Antonio’s wife and kids, and realized how many people around him have been living in fear and waiting – praying really – for him to stop bullfighting, I knew there was a fuller story here that deserved a feature-length movie. It’s one thing to tell a story about a man’s obsession with something that nearly gets him killed on a weekly basis. It’s another thing to tell the story of his loved ones, and how it keeps all of them on edge for two decades.

HtN: How hard was it to shoot those bullfighting scenes? I can almost imagine you’d have to take on a combat journalist’s mentality of disassociation.

IM: The bullfighting scenes were very challenging to shoot for two reasons. First of all, it’s just nerve-racking and dangerous to be hiding behind these little flimsy wooden separators – inside the bullring! – with your camera and lens peeking over them, and attracting the bull that is not at all happy about being locked in a bullring. The second challenge is just watching and filming this brutal spectacle. These bulls get slaughtered right in front of you. While the adrenalin keeps you focused on your story and the shots you need to get, your stomach is turning. My very talented, longtime DP Boaz Freund, who spent three years as an army videographer, was having a very tough time. Luckily he’s so unbelievably good you’d never be able to tell.

HtN: We actually started a sticky conversation at the Hot Springs Documentary Film Festival – where I programmed “Gored” – about the moral filmmaking quandary that the doc presents. As you know, I’ve likened the film to the uneasy cinematic equivalent of Sebastião Salgado’s photos. What I mean is that the artistry behind the lens lends a beauty and nobility to what is, in truth, inexcusable suffering (of animals in this case. Poverty porn becomes slaughter porn). Do you want to add your thoughts to that?

IM: I think films and filmmakers have a moral obligation when it comes to both their subjects and their audiences. Too often we watch films where the filmmaker falls in love with something dark or poisonous they’re depicting. That’s why Antonio Barrera was such a perfect choice as a subject. He’s hardly a poster boy for bullfighting, which I did not want to glorify, and so in his struggles you get to see bullfighting at eye level – brutal, bloody, and painful. Anytime we see bullfighting as romantic in the story those moments are often immediately followed by moments of sheer brutality. And sometimes even mundanity that drains the romance out of the performance. It’s always a matter of being true to the point of views represented in the story. Antonio wanted to be a great matador who performed with grace. But really he was an over achiever who got punished repeatedly for his dream. In that sense the only times bullfighting seems aesthetically pleasing in the movie is when it represents an ideal he was raised on, but could never achieve.

HtN: We first met at Hot Springs, but you premiered the film in NYC last spring at Tribeca – and also screened at Copenhagen’s CPH:DOX (which I also attended) this past November. How have different audiences reacted to the doc’s portrayal of such a controversial subject?

IM: It’s been a really fun and engaging festival run. As you can imagine people definitely experience this movie in their guts, for better or worse. Most people get that this is not a pro-bullfighting documentary, but they are still angry at the phenomenon itself. So the post-screening discussions have been lengthy and emotional – just the way I like it!

People feel torn between their feelings toward this man, who is punished over and over again because of a destiny that has been decided and put in motion for him by his father (himself a failed bullfighter), and the brutality of his actions. Also, people’s general opposition to bullfighting often brings up a very intense conversation about our treatment of animals. Bullfighting takes most of the heat because the killing is done in broad daylight in front of a paying audience, while the chickens and cows we eat are killed out of sight and in shady inhumane conditions. Both are brutal practices – only one of them is in your face while the other is hidden.

HtN: Finally, did making the film upend any preconceived notions you may have had about bullfighting – or the matadors who devote their lives to such a bloody profession?

IM: I knew it would have been silly to make a movie about bullfighting that was just another simplistic critique of bullfighting. Plus, that’s just not my kind of filmmaking. We all know bullfighting is brutal and being phased out of the world. I wanted to approach it without judgment. Geoff and I were fascinated by the fact that this ancient ceremony was still in existence, and wanted to understand why – as opposed to just condemning it. Also, this wasn’t purely about bullfighting to us. It was about a man trapped in a world that he was born into, and expected to not only survive in but master. Many of these matadors are sons of failed bullfighters, carrying the torch for their fathers. That was easy to identify with, and transcended the world of bullfighting.

– Lauren Wissot