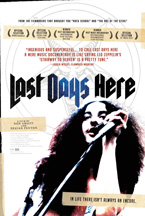

A Conversation With Don Argott and Demian Fenton (LAST DAYS HERE)

When Don Argott and Demian Fenton first pointed their cameras at Bobby Liebling, they weren’t doing it with the intention of making a 90-minute documentary called Last Days Here. But it wasn’t long before this tentative video project turned into a years-in-the-making, labor-of-love, bona fide feature film. As the leader of underground heavy metal heroes Pentagram, Liebling had a knack for flushing any opportunity that came his way down the toilet. The number one explanation for this: drug addiction. Most documentaries are better served when a viewer has no idea what they are getting into, and in the case of Last Days Here, that idea is truer than it’s ever been. But one thing must be clarified: this film is as far from a generic rock-and-roll documentary as you can get. By concentrating on the complex humanity of the situation, it becomes an altogether more revelatory experience. On the heels of the film’s theatrical release at the IFC Center on March 2, 2012 thanks to Sundance Selects—***even better, it’s yours for the renting on VOD right now***—I got on the phone with co-directors Argott and Fenton to discuss the many delicate factors involved in producing such an awesome too-surreal-to-be-real tale.

When Don Argott and Demian Fenton first pointed their cameras at Bobby Liebling, they weren’t doing it with the intention of making a 90-minute documentary called Last Days Here. But it wasn’t long before this tentative video project turned into a years-in-the-making, labor-of-love, bona fide feature film. As the leader of underground heavy metal heroes Pentagram, Liebling had a knack for flushing any opportunity that came his way down the toilet. The number one explanation for this: drug addiction. Most documentaries are better served when a viewer has no idea what they are getting into, and in the case of Last Days Here, that idea is truer than it’s ever been. But one thing must be clarified: this film is as far from a generic rock-and-roll documentary as you can get. By concentrating on the complex humanity of the situation, it becomes an altogether more revelatory experience. On the heels of the film’s theatrical release at the IFC Center on March 2, 2012 thanks to Sundance Selects—***even better, it’s yours for the renting on VOD right now***—I got on the phone with co-directors Argott and Fenton to discuss the many delicate factors involved in producing such an awesome too-surreal-to-be-real tale.

Hammer To Nail: Obviously you guys had no idea what type of ending this story was going to have when you started filming Bobby, and from the beginning, things looked about as hopeless and unpromising as they could possibly be. Did you have any sort of ethical doubts about embarking on this project?

Demain Fenton: The first footage you see of Bobby was from the first day that we shot. And on that ride home—it was from DC to Philly—we sat in the car and we were completely confident we didn’t want to make a movie that just documented some poor guy dying in his basement. And I think we just kind of thought the project would go nowhere. But the one thing that kept it alive was when Bobby started playing us his music, and air guitaring and stuff, you could see this glimmer in his eye, and you could see and hear in his tone of voice his passion for music. And you could tell if the guy was gonna stay alive, it would be because of that. And things moved at such a slow pace with this film, it would just be those little snippets of life that would draw us back. So any kind of moral question like exploiting this guy damaging himself in his basement, it was almost like we needed a report from him or [fan-turned-manager] Pellet that he was not damaging himself. And then, after that, we became part of his life, I think, intertwined with him and his mom. I think we actually played a real supportive role, positive people who didn’t want to go down there and smoke crack with him. At that point he had very few visitors. He did have a few, but most were just people who wanted to come and get high. In some way, we became this positive force, just with the visits down there.

H2N: Editing and structuring is always important, but in the case of this film it seems insanely tricky and crucial. Like, there’s an increasing, inevitable tension that emerges throughout all of these ups and downs that make us wonder why not just Pellet, but why we, are still hanging around this guy. But it never tips all the way over the edge. Was that something you guys were hypersensitive to in constructing the film?

Don Argott: I think so. The difference in the way that we’ve done this film versus some of the others that we’ve done, is that this film was pretty much all in the can before we started really putting it together. Whereas every other film that we’ve done has been cutting as we go, and kind of feeling the story out. But the reason this film took so long is that Bobby’s life moves at a snail’s pace sometimes, and we were also doing this project as very much a labor of love—there was no funding, there were no investors. There was no pressure to make the film other than we thought we had something that was special and we felt that we could tell a great story. There was no ticking clock element to it. So in a way, the film really benefits from the patience that we had in letting the story evolve the way it did. And then once it evolved and we had the hundreds of hours of footage that we had, we knew we could start from day one and we already knew what the journey was going to be. If we were cutting this film as we went, it would’ve had 55 different versions of like, “Oh wait, now we’re going down this road, but now we’re not anymore.” Because we didn’t start cutting until the film was totally shot, we had the luxury to really map out a narrative that made sense and that we knew we could get from point A to point B with.

Don Argott: I think so. The difference in the way that we’ve done this film versus some of the others that we’ve done, is that this film was pretty much all in the can before we started really putting it together. Whereas every other film that we’ve done has been cutting as we go, and kind of feeling the story out. But the reason this film took so long is that Bobby’s life moves at a snail’s pace sometimes, and we were also doing this project as very much a labor of love—there was no funding, there were no investors. There was no pressure to make the film other than we thought we had something that was special and we felt that we could tell a great story. There was no ticking clock element to it. So in a way, the film really benefits from the patience that we had in letting the story evolve the way it did. And then once it evolved and we had the hundreds of hours of footage that we had, we knew we could start from day one and we already knew what the journey was going to be. If we were cutting this film as we went, it would’ve had 55 different versions of like, “Oh wait, now we’re going down this road, but now we’re not anymore.” Because we didn’t start cutting until the film was totally shot, we had the luxury to really map out a narrative that made sense and that we knew we could get from point A to point B with.

DF: And I think that exactly what you’re talking about with this balance—there are a lot of things being balanced throughout the film—those were always our rough cut notes. Many times, they were based on that balance. Like, Bobby’s an addict, but you wanna feel sympathy for him but you don’t wanna feel too much sympathy for him. Pellet, he’s a fan but he’s also maybe this weird fanboy? Or is he now a friend and driven to really help this guy? And I think that we tried really hard, because walking into that situation, you understood everyone’s take on the scenario wasn’t so cut and dry. Bobby’s parents, everyone says, “They should kick him out of the house!” But, no, it’s not that easy. And we always had to work to find that balance with everyone when we were structuring the movie.

H2N: I was going to ask if you guys assembled this as you went along, but having clarified that you actually sat down to edit once you had everything shot and therefore had a plan as to where things were going to go, that dramatically changes the process. Did you guys just talk it out or did you do a written outline and note cards, or did you do an assembly based on the particularly memorable moments that you knew you had captured?

DA: I think we knew what we had to work with in terms of the moments that we felt were going to make it into the final cut. We note-carded it, we talked about it, we did all those things. It was a constant evolution. And all that is to say that we certainly didn’t have it all figured out on the first pass. I mean, it still went through a lot of different revisions. We saw what was working, what wasn’t working, the things we thought were gonna pay off a little bit more that didn’t pay off as well for whatever reason. So it was still an evolution of really crafting the story in the most effective way, but at the same time, again, of having that luxury of knowing what we had to work with, and really being able to take that step back and say, “Okay, this is what we have. We know we’re gonna start here. We know we want to end here. How do we get there with all these little things that happened along the way?” And still keep all these other things in mind like you would do with any film, whether it’s narrative or documentary, you’re still dealing with characters and character development.

DA: I think we knew what we had to work with in terms of the moments that we felt were going to make it into the final cut. We note-carded it, we talked about it, we did all those things. It was a constant evolution. And all that is to say that we certainly didn’t have it all figured out on the first pass. I mean, it still went through a lot of different revisions. We saw what was working, what wasn’t working, the things we thought were gonna pay off a little bit more that didn’t pay off as well for whatever reason. So it was still an evolution of really crafting the story in the most effective way, but at the same time, again, of having that luxury of knowing what we had to work with, and really being able to take that step back and say, “Okay, this is what we have. We know we’re gonna start here. We know we want to end here. How do we get there with all these little things that happened along the way?” And still keep all these other things in mind like you would do with any film, whether it’s narrative or documentary, you’re still dealing with characters and character development.

I think along the way, because we were the outsiders in one sense, we were asking the questions that we felt any audience member would ask. Early on, we’d be spending time with Bobby and it was easy to get frustrated and say, “I feel bad for his parents, why don’t his parents just throw him out of the f**kin’ house? Enough already!” So we asked that as a legitimate question and the answer we got was very complex, and it makes you realize that the situation is not as easy as throwing him out of the house. Because the reality is that’s someone’s son, and that’s someone’s life that they would be kind of willingly destroying if they let that happen. And that’s not a judgment call for someone like myself or Dem to make. That’s why throughout the process we were asking those tough questions to everybody that was involved, and got really interesting answers, answers that informed where the narrative was going next.

H2N: This film is an interesting case in that it might work even better for viewers who don’t have any interest in or knowledge of heavy metal and especially Pentagram. Two questions: 1) has it been difficult to convince people that the film transcends its more superficial ‘heavy metal/music documentary’ appearance? And 2) because of that, has it been extra rewarding to see the post-film reaction of people who had no idea what they were getting into?

DF: We always knew that we wanted to make a film that was way beyond a “heavy metal doc.” That was one of our goals from day one. You know, if you want to figure out the history of a band, go on Wikipedia and go on YouTube and you’re good. We wanted to make something deeper than that. I think that from the reviews the film gets, to hear someone comment on that, that it’s way beyond a heavy metal film—people can turn off heavy metal real quick, they can turn off addiction stories real quick. This seems to transcend for people, and that was one of our main goals. That’s one of the things I’m most proud of about this film.

DF: We always knew that we wanted to make a film that was way beyond a “heavy metal doc.” That was one of our goals from day one. You know, if you want to figure out the history of a band, go on Wikipedia and go on YouTube and you’re good. We wanted to make something deeper than that. I think that from the reviews the film gets, to hear someone comment on that, that it’s way beyond a heavy metal film—people can turn off heavy metal real quick, they can turn off addiction stories real quick. This seems to transcend for people, and that was one of our main goals. That’s one of the things I’m most proud of about this film.

DA: To the second question, it is that much more rewarding, because I think people go in with the preconception of, “Oh, this is gonna be just a typical VH1 “Behind the Music” doc where a guy hits rock bottom and tries to pull himself back together.” And the most interesting thing, which you were there for when we showed the film in Sarasota [at the 2011 Sarasota Film Festival]—there are certainly progressive people that check out the films, but our audience was mostly 60 and over, and it was really kind of amazing because both of us, Dem and I, talked to people individually after the screening, and they all responded in such a positive way. It was so surprising and really cool. One woman said to Dem or me, I forget who it was, but basically said, “My grandson is an addict, and I feel like the way you guys showed addiction in this film is so raw and honest and unlike anything I’ve seen in any other film before, it was really great.” So, totally unexpected. You’d think that as soon as the film starts, you know, like half the people that were in that audience that were over 60 were gonna walk out. But they all stuck with it and I really feel that they got more out of it, and it helped us realize that there was a bigger audience for this. Whether we can get to that audience is a different story, but I think that there is another audience for this film aside from the obvious heavy metal or music fan.

H2N: As someone who has made a doc about a musician, I’m interested in how you guys approached the question of Bobby’s role in the screening and marketing of the film. How did you navigate his participation after the fact?

DF: It has nothing to do with Bobby and his personality. It has to do with the story, which is so surreal, that we want to toe that line between giving the viewer clues to how it ends up. And I think incorporating Bobby gives clues. It’s almost hard to talk around, I don’t know how to answer that, you know what I mean?

DF: It has nothing to do with Bobby and his personality. It has to do with the story, which is so surreal, that we want to toe that line between giving the viewer clues to how it ends up. And I think incorporating Bobby gives clues. It’s almost hard to talk around, I don’t know how to answer that, you know what I mean?

DA: That’s been our elephant in the room with all these things moving forward. It’s like, where is that line between giving the film away and being okay with that versus holding back what you know is gonna [lead to a] much better payoff for the overall audience. And still having to navigate marketing and advertising the film a certain way. For us, it’s not about keeping anybody away. It’s more just protecting the integrity of the experience of watching the film. People always say, “I can go online and find out anything I want to about where he’s at,” and that kind of thing. But to me, that’s like jumping to the end of a novel. If you’re that kind of person, then go for it, you know? But I feel like my favorite movie experiences have always been when somebody says, “Dude, go see this movie, and don’t learn anything about it, just go and watch it.” And I always feel like those experiences are the ones I remember the most, because when you start reading five, six, seven reviews of a film before you see it, and you see the trailer, and you see selected scenes, at a certain point you go in with this feeling of knowing what the film is. You’re smart enough that when you watch trailers, you see a thing in the trailer and then you’re watching the movie, you know, “Wait, I haven’t seen that part yet, I know that guy they say is dead, I’ve seen him in the trailer and he’s not dead yet.” There’s that line, and it’s a weird line to walk. We’ve tried to walk it delicately with this film in particular.

— Michael Tully

Pingback: HOME VIDEO PICKS – Hammer to Nail