(On April 2, 2015 the world lost one of the great unsung Masters of Cinema, Manoel de Oliveira at the ripe old age of 106. With 62 directorial credits to his name as of 2014, de Oliveira holds the record for oldest working filmmaker and very few are even close. Our own Evan Louison goes deep on the career of the Portuguese filmmaker and intertwines his own amazing story of getting to work for de Oliveira as a young man, scarecely knowing he was learning from a true artist)

God?

There is no longer a place on earth for him.

But he remains. There is truly a right place for saints.

God exists. The universe was created by Him.

But what good would the universe be…

if men, if humankind disappeared? The universe would be useless.

Or is it possible that it has a purpose of its own, even without the existence of man?

We want to imitate God. That is why there are artists.

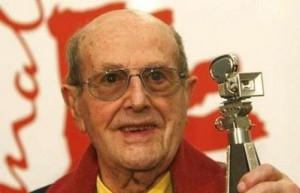

The above passage, captured by Wim Wenders in his sequel to The State of Things, is really the best jump off point to the work of the cinema’s oldest craftsman (currently and in history— though George Abbott surpassed Oliveira in age, living to 107, he directed his last film, Damn Yankees, in his 50’s ), Portuguese master Manoel de Oliveira, who passed into the ether this week after more than 80 years at the helm.

Artists want to recreate the world, as if they were small gods.

And they do… They constantly rethink

history, life, things that happen in the world,

things that we think happened,

but only because we believe.

Because, after all, all we have is memory.

Because everything has already passed?

But who can be sure what we think happened

really happened? Who should we ask?

You wouldn’t be able to parse the full breadth of Oliveira’s output without considering the time. Not just the time in his pictures, at certain moments languid and static, observational but never cold, but the time it took to make them. This is someone for whom the vast expanse of history was not an enemy, not to be feared or felt with any notion of hesitancy. Instead Oliveira repeatedly took history, specifically Iberian history, to be analogous to greater truths, ones he held to be self-evident.

Therefore this world, this supposition,

is an illusion. The only real thing is memory.

What lesson, what purpose can time provide for us? This seems to be the question for so much of MDO’s work. He chose to place himself in the long tradition of gentle storytelling, in the same instance taking influence from both Rossellini and Buñuel, to examine the different compartments and chapters of Portuguese triumphs, defeats, scandals, tragedies, and mystical visions throughout the span of the modern and ancient era, and to struggle with the resolution of those various pasts into one current, present life, perhaps to better prepare for what may lie ahead.

But memory is an invention. Deep down,

memory is… I mean, in the cinema

the camera can capture a moment.

But that moment has already passed.

In January 2007, I received an email from Robin O’Hara, my boss at Forensic Films. The subject line read simply, “MDO.” In it was an attached script and a plea for New York production support from a French producer looking to arrange a shoot for less than 1 week in Manhattan and Brooklyn, with a crew arriving from Paris, consisting of Oliveira’s French production designer (Christian Marti) and cinematographer (Sabine Lancelin), in a matter of months. At the time, being a relatively young (23) assistant, I’d neither seen nor heard of this paragon of cinematic longevity, thus all the more unsettling when greeted with the realization that I was about to help his most recent (and possibly, as every picture past a certain age must potentially threaten to be, his last) film come to fruition. For someone as idealistic and naive as I still was then, I felt over my head at least, and unsure at best of the thickness of the ice beneath me. “Crash course in cinematic history this month…,” Robin wrote me — “…as Scott [Macaulay — producer & founding partner at Forensic] says — this is not someone you say no to.” And so, we didn’t. Instead, we were off to the races, flaps down and shields up, in one of the strangest experiences in (not) – making a movie I’d had to that point.

“To flee the storm our voyage took 16 days. For the arrival, we all got up at daybreak, eager to see

the big city lights and the

legendary skyscrapers!

What a disappointment! The port of New York was shrouded in mist…”

(screenplay for Cristóvão Colombo – O Enigma, 2007)

I chose this passage from Oliveira’s script for this piece because it is exemplary of so much of the wonder one could sense in his own desire to shoot in the States (a man who never approached the shores of Hollywood or American filmmaking in general), and how tricky an expedition it would become, his first and only attempt to incorporate his own ethereal worldview into the immigrant culture and landmarks of New York, and the Iberian-American secret history he read into everything. For MDO, it would seem that the entirety of the modern world was still descended from the times of empires and conquest, and in one way or another, these signifiers and latent traits needed to be dealt with, if not violently, then through contemplative measure. His own upbringing, one of privilege and entitlement (born the son of a wealthy Lightbulb manufacturer, owner and founder of Portugal’s first factory of the sort), Oliveira seemed dead-set from an early age to take on the identity of advocate for the lower-class, his first film Aniki–Bobo (1942) seeming to be torn from the same parchment as Rossellini’s Paisan and de Sica’s Sciuscià (Shoeshine). But his own efforts (aside from directing, he also appeared as an actor in a number of productions, most notably 1933’s Lisbon Song) were stifled by the Estado Novo (New State) regime, led for nearly 40 years by a man never actually appointed President, António de Oliveira Salazar (no relation).

The Salazar censors controlled everything, and by this, we should say, EVERYTH|NG in the republic, thereby limiting MDO to an apparent life-sentence as an executive of his father’s factory, and silencing his cinematic output for the greater portion of his prime. MDO, like many of Portugal’s young, was considered a threat, at least according to his own version. Much has been said of what this now no longer young man who once dazzled onlookers in various athletic pursuits (from trapeze artistry to diving to racing cars, MDO was clearly equipped with the prerequisite physical constitution and endurance without which a future centenarian film career would probably have been impossible) he devoted his later years to, but very little can truly be known of his time trying (and subsequently, repeatedly, failing) to mount one narrative project after another, for the better part of three decades. “…a long process of reflection,” he would call it later, claiming that it took just that amount of time (from ’42 to ’71 — Salazar’s regime withered away between ’68 and ’74) to “…become aware of what I wanted to do….”

What the cinema does is draw a shadow

of that moment. We are no longer sure

that the moment ever existed outside the film.

Oliveira’s work seeks to contend with the core of history, with the same problems that plagued our ancestral predecessors and the ramifications for lacking a solution, through a plaintiff, pedestrian prism. His stories include characters from all walks— military service, fish mongering, monarchy, academia, medicine— and perhaps most importantly, cinema. In this light, they appear transparent against their backdrops, as if present in an educational diorama only as placeholders, for example or mouthpiece service for MDO’s own speculation on the systems that guide civilized culture, and have so since its beginning. In ‘Non’, ou A Vã Glória de Mandar (‘No, or the the Vain Glory of Command,’ 1990), perhaps MDO’s most politically outward film (and one whose chromatic and tonal influence on Malick’s Thin Red Line is undeniable and striking) traces the history of Portugal’s military through a string of agonizing defeats, juxtaposed against a troop deep-set in the African wild, as they await guerrilla attacks and debate their own purpose in the midst of a transformative, doomed colonial war. In the back of a convoy, one of the young soldiers sighs and smiles: “We are always at war with the Spanish.” This acknowledgement of the pursuit of power’s true implications in the colonial region and back home, and how such pursuit formed in Portugal a fledgling, fiercely perseverant, multi-racial culture, is merely the surface of the statement’s connotations, as Oliveira lets the most benign of musings fall from the lips of his characters as gently as the leaves from the overhanging jungle canopy, dripping with insinuation.

When finally caught off guard, ambushed with a machine gun in a jungle clearing, the unit is set upon with force, leaving casualties and wounded among them, the very same soldiers who seemed to yearn for something to happen their whole journey, their whole time in wait. Suddenly, when the firefight dies down, there is a screaming, an almost absurd, comic screaming. It is the lone perpetrator of the ambush, an African man in civilian clothes, gutshot, clutching his insides as he staggers from the scene, wailing the whole time. The troops watch him go, as if in shock. It is this suspension of animation, this sudden suction of all immediacy (mainly by showing everything in extremely wide frames) from the proceedings, that leaves us with the sense of something mythic taking place, something fitting right in in the span of centuries laid out for us over the course of the picture.

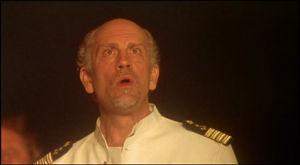

Such misleading dialogue is not out of place in MDO’s world. In Un Filme Falado (A Talking Picture, 2003), a group of passengers at sea, all women, sit with the ship’s captain, extolling the burden of a life’s work, of a future without a legacy, and marvel at each other’s respective qualities, the captain, played by John Malkovich, having no children and never married. Commenting somewhat innocuously, one passenger replies to the captain, “You still have time…,” to which he smiles and replies, “Yes, well, I would say there is still time to avoid any of these fates…” It is not a flippant response. The burden of living without passing anything on, the shame of living throughout time and not spending every second of it enthralled and pressing onward, this would appear the greatest sin in MDO’s scripture. As he said himself, “All my films deal in some way with the problem of sin and the possibility of redemption, and in this sense they all derive ultimately from the same source.” It has been speculated that Un Filme Falado, which ends in tragedy, was conceived as a response to 9/11.

His crew arrived shortly afterward, and it was like a riptide. It was my first time even attempting to help coordinate for a production, and at that point, let’s just say I was stretched past the point of my own experience and firmly in waters I could barely tread. All of a sudden we were in the middle of a storm— certain things would have been required (ie; more time) that could have made for an expedited process, due to VISA obligations, union regulations and Mayor’s Office permit guidelines, this was not to be. All the same plenty of ears perked up when MDO was mentioned, and a welcoming squad of various NY downtown film fixtures (lighting/cameraman Michael Barrow among them) gathered to help support. Long nights of location scouts all over the waterfront on both sides of the bridge, discussions of logistics— shooting at a breakneck pace for a tiny budget, we were wracked with problems I didn’t even understand at the time, mainly regarding the fact that if anything went wrong— there would be no second chance. The budget restricted the number and kind of permits that could be acquired, and subsequently, the pressure to make sure locations could be secured even without them and that they would be reliable once we finally had MDO present, seemed heightened, drastically so at times. Nothing will lead me to forget running all over Red Hook, Gowanus, Dumbo, and the Two Bridges as well as the Battery in Manhattan, looking for the perfect place to cheat for Ellis Island, as called for in MDO’s text, and always, always, always, in the dead of night. I was the youngest person involved, and felt really cool.

The thing that stands out in my mind now is that the idea of MDO alone was enough to spur such excitement from me — at this point an already sadly jaded individual. I had never seen frame one of any of his films at this time, and the script seemed academic and like a historical photo album more than a film— but that’s not what mattered. It was the idea that this was someone who had given up — quite literally — for so much time, and then dove back headfirst, head on into cinema, when finally he felt he could, and never slowed down. The concept of longevity was one that eluded me then, and is only peaking my interest even now— but MDO, MDO was it. He encapsulated a certain, effervescent grace, even only as a notion of a person, an elusion of a character I’d yet to encounter firsthand, like a relic of the long-since-passed. When shooting plates for Green screen projection was suggested, MDO required further explanation. “‘Like a matte painting,’ I told him,” Robin relayed to me afterwards in some late night caffeinated conference. “And you know what he said back?” She paused for the proper effect. “Oh yes, I just love these modern techniques.”

Push came to shove, and eventually it became clear that there was very little assistance that could be provided (aside from pre-production support) that would be consistent with certain signatory regulations that had to be maintained with the various guilds. In short, we wouldn’t be on set when the time came. I was more than a little defeated— I had really had my heart set on the moment I could watch MDO work. This project was to be special— his first in the US, his first appearing in his own, self-directed work, his wife’s first appearance in a film of his as well— and it would happen. But like so much of what we learn through our formative experiences in making pictures, sometimes the biggest contributions go uncredited, unnoticed, and ultimately forgotten.

Or is the film proof that the moment existed? I don’t know…

I know less and less about that.

We live, after all, in permanent doubt.

And despite that, we live with our feet on the ground.

Then one day, I got a call. “A car is coming to pick you up in 5 minutes downstairs, get ready.” From Robin’s voice on the other end, I had a feeling it was something special, but she didn’t tell me what. I hurried down and got inside, Robin in the back waiting. We whipped up the FDR, in silence. I remember it was cold and windy that day, though the sun was shining. “Are we going to the UN?,” I joked to her, nervously hoping for some response. “No, but they’re probably going to get arrested if they try to shoot there.” I knew it— I was about to meet MDO. We got to our destination, some corner overlooking the East River (and sure enough, the United Nations), but the crew was nowhere in sight. We called and called, frantically trying to find them. Finally we saw a van of people loading equipment and jumping into the back of a 15-pass, trying apparently to beat either the light or the authorities, and knew we were in the right place. I asked the Line Producer where everyone was— “He wanted to shoot over there, and just started walking by himself. We’re trying find him to catch up with him now…” I followed Robin, who followed the crew, but everywhere we stopped, we were told, “MDO? He’s just been here…” like some kind of comic opera, or a practical joke. Perhaps he didn’t exist after all, after all this waiting, it would be a ghost in the director’s chair in the end, waiting for us when we finally arrived to set.

Suddenly, as we neared a back street near Grand Central, I saw him. Striding towards us, hat, glasses, and cane all elegantly arranged upon him like a costume, with a sort of stunned look on his face. I’ll never forget how eyes his eyes appeared, like a baby’s eyes, like he was high on everything around him, like everything he saw, he was seeing for the first time. Robin shook his hand and introduced me as her assistant, and I was shellshocked with awe, unable to speak. It didn’t matter. MDO shook my hand, tipped his hat, nodded and looked me straight dead in the eye— “I don’t speak English,” he said, in perfect English. and like that, he was gone, striding past us, even though everyone he now was headed away from had previously come from right where he was headed, and were looking for him. Unconcerned, he seemed absorbed in greater issues. Perhaps a secret history. Some kind of narrative only he understood. I couldn’t help but laugh. Digging out this script when I read of his passing, I can’t help but suspect that of the films I’ve yet to see of his (many they are), I’ve still so much to uncover, with some luck, and maybe some time.

“The transformation… that’s yearning!… like a premonition… This word yearning,

Whoever invented it Must have cried,

…When first they said it.”

(last line of dialogue, Cristóvão Colombo – O Enigma, 2007)