A Conversation with Christina Clusiau and Shaul Schwarz (TROPHY)

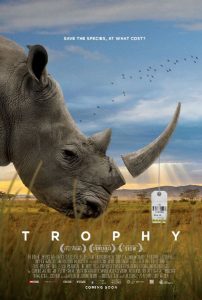

I met with Christina Clusiau and Shaul Schwarz, co-directors of Trophy (which I also reviewed), a disturbing and complex documentary about trophy hunting, on Saturday, March 11, 2017, at SXSW. Their film premiered at the 2017 Sundance Film Festival, and offers no easy answers in its presentation of the challenges of how best to save the endangered species of our planet. It does, however, ask provocative questions, considering the potential value that managed hunting can have in incentivizing conservation efforts and delegitimizing poaching in communities that live near the threatened animals. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation.

Hammer to Nail: So I want to start out by saying how much I appreciate the complexities of the issues addressed in your film, and the even-handedness of your presentation of them. Still, there is some disturbing footage. Could you describe what, for you, were some of the most challenging aspects – for the two of you – in making this film?

Hammer to Nail: So I want to start out by saying how much I appreciate the complexities of the issues addressed in your film, and the even-handedness of your presentation of them. Still, there is some disturbing footage. Could you describe what, for you, were some of the most challenging aspects – for the two of you – in making this film?

Christina Clusiau: I think, emotionally, one of the most challenging scenes that we shot was the elephant hunt. You know, you follow elephants for days at a time. We had been on previous hunts, but there the connection of the hunting was further away. The shot was much further away, and when we arrived at the animal, the animal had already been killed. But the elephant, itself, was quite emotional, because we were so close to it, and also I didn’t realize how long it would take for the animal to die, just because of the fact that it’s a large animal. I didn’t expect that out of myself, to be so upset about it.

Shaul Schwarz: Yeah, I think, shooting-wise, that probably was the hardest scene. I had never seen elephants before, in the wild. They are very majestic and very beautiful creatures, and I think, to some degree, that’s what we wanted to make this movie about, this battle of mind and heart. The heart didn’t like what it saw. It was very painful, to the point that we both cried, the hunter, Phil [Glass, one of the film’s main subjects], cried. Even the professional hunter cried. It was surreal. It was one of these things where your heart wants to say, “let’s reverse time and make this not happen,” but it did happen, and then, two hours later, some villagers come by, and they’re happy. They’re clearly happy. And, to us, was what this movie is all about: dealing with that complexity and challenging what we feel and what we think and how the two sort of impact each other.

HtN: You, Christina, grew up in more of a hunting environment than did Shaul, so this was not unfamiliar to you.

CC: Well, the nature of the animal was. I, too, had never seen elephants in the wild. But I grew up in a place – northern Minnesota – where everyone I knew hunted, and I, as a kid, even sat in deer stands with friends, and it’s a way of life. It’s what people do. And so the idea of hunting was always part of my world. The vastness of trophy hunting, or the expanse of the industry, was something that was very new to me. And, also, the African elephants were very new to me.

HtN: But for you, Shaul, no hunting in your background.

SS: No hunting whatsoever. Israel is not a hunting kind of place. And one example that I give to people is that when I came to this country, I couldn’t accept the idea of deer hunting because it was “Bambi.” They are majestic creatures. I hadn’t really seen deer that often, and when I saw one in upstate New York, I was thrilled. I love animals and it was beautiful and I couldn’t understand why someone would shoot it. But when you understand that there are, I think, 30 million of them in the U.S….

HtN: Yes, there’s a major overpopulation issue, and where I live, in Maryland, if the deer are not culled, they are hit by cars and…

SS: Yeah, and to simplify it, there are a lot of deer in this country. But to me, it’s still a beautiful, cute animal. And so that’s the complexity that, to us, got interesting as I got educated about this. But going in to the movie, I didn’t know about it and was definitely thinking from the heart.

Shaul Schwartz, our Chris Reed and Christina Clusiau

HtN: Right. So you mentioned the villagers a moment ago. I really like your film. The only thing missing, from my point of view, is the direct voice of this indigenous population. We have a lot of talking-head interviews from different perspectives, but we never have a single articulate spokesperson from that population, although we do hear from the game warden [Chris Moore]. I’m curious: did you consider shooting an interview with someone like that, or did you shoot one and just not include it?

SS: Yeah, it’s too bad you say that, because we fought hard to do it, and we wanted…and Chris is local, he’s just not black, and I just want to mention that. But with that said, we did interviews with locals, but we wanted it to feel that it wasn’t edited. We wanted to hit these more vérité scenes with the locals. To us, it was more magical – or bullet-proofing the point – when a woman reacts to the anti-poachers and says, “You have to kill this lion, but we understand that it is of value to us,” rather than have her say it in an interview. Or showing the guys eating the elephant. We wanted to make that more in vérité, to make sure that people don’t…you know, this issue is so sensitive, that as we kind of got further down the line of the edit, we were constantly second-guessing what we thought people would be upset about. And what is OK that they’ll be upset about and what are we representing in the right away. So we didn’t do some interviews, and ended up using the vérité scenes.

CC: Yeah, and I think that came up a lot, not using the local voice. But we wanted to show it in vérité, as we were experiencing it, instead of pulling in interviews of experts.

HtN: Understood. I won’t second-guess your process…

CC/SS (both): No! It’s a good question.

HtN: You also don’t have any voices of outrage, other than that of on-the-street protesters in Vegas, to balance someone like [main subject] Philip Glass’s confidence in what he’s doing. I think that’s to the strength of the film. Did you consider having more of an outraged opposition?

SS: Well, we have some opposition. Not a lot, because I think what we were challenged with, coming in, was that we were the opposition, so we wanted to portray those who believe in sustained utilization. That was our banner. How do we give them a voice, without just buying into everything they say? So it was clear to us that that should be the majority. A movie about anti-poaching has been done, and there have been many movies about animal rights, and great ones. We wanted to scrutinize this unpopular notion of sustained utilization, the greater idea of putting commercial value on an animal.

So we tried to counter it a little bit. We wanted to show weaknesses in the defense, at times, showing what canned hunting looks like, letting Philip say something that he believes in, like “evolution doesn’t exist, and I believe these animals were placed here by God for my usage.” It’s not something that I believe in. But we gave these people a fair representation of what they believe in. And so to me there are holes in their defense, but there’s a lot in what they do, and I think that’s why we didn’t really want to fall into … yes, we included Born Free, and created a debate between them and [rhino breeder] John Hume, but you know I feel like that was less surprising, in a sense.

CC: And I also think that the opposition – the animal-rights side – is the majority of a lot of people that will be viewing this film, and so to look at it from the other side, to us, was really important, because it’s a side that people don’t really see as much. And to give voice to that – to give experience to that – was important to us. I think it would have been easy to make a film that was coming at it from the animal-welfare side, but I think it’s irrational, and I think it’s not fair, because there are two sides to every story.

SS: Just one point to add to that. When Cecil [the Lion] happened – and we were in the middle of production – I thought, “God, if I didn’t know anything about this, I would be outraged, and I would be screaming.” But when it happened, I was kind of like, this is this avalanche of, sorry, but kind of nonsense. If you want to change it, change it at the core, but don’t blame an individual who bought a hunt, did it legally, and go protest at his house and put him out of business. You don’t have to agree with that, but … So we saw this avalanche, which strengthened our belief to give voice to the unpopular.

HtN: So, leaving Philip Glass aside who, agree with him or not, is at least behaving according to certain core principles that you can respect as principles, you have scenes in the film of people who surely must have had some sense that being represented in this way – drinking, smoking, putting their beer down for a second so they can go shoot a crocodile in the head – might not be seen well. Did you have any difficulties convincing such groups of people to be on camera, or were they happy to be filmed?

SS: It was hard to get access to any of this world. We worked hard to get trust, to say, “we’re going to portray you in an honest way.” I believe we portrayed that hunter in an honest way. We have tons of footage of that kind of stuff. This is one occasion that got cut into the film, but there is a lot. I think it also happens more than hunters would like to admit. What I would point out is to be careful not to throw all of canned hunting under the bus. And that’s a term the hunter’s hate.

CC: Of course.

SS: But some of these enclosed areas show an extreme cinematic moment. To me it comes down to the welfare of animals. In my opinion, no matter what you tell me about economic power and numbers, it’s very hard for me to accept the idea of putting a lion in a cage until you release it to be hunted. But if you talk to me about a magical animal like a giraffe, and it’s living its life on an empty ranch and it’s running around and it’s quite big and it has a good life and it’s taken when it’s old, that’s not a challenging hunt.

But if we created a market to force breeders and landowners to create this thing that South Africa has proven as one of the best conservation methods – certainly in Africa, if not the world – then that’s something that we have to consider, even though it’s so…I don’t want to shoot a giraffe. That’s not my thing. But I try not to judge it that way, after I’ve gotten into the subject and realize the success they’ve achieved. And I think almost any ecologist looking scientifically at it would agree to South Africa’s success.

HtN: And I think your film does a great job presenting that point of view and the academic in the film…

CC: Craig Packer.

HtN: Yes, he does does a wonderful job articulating that point of view.

CC: Yeah, I think that was really important to show this duality of the South African model, where maybe it’s not ideal – maybe it’s not this perfect environment of hunting – the reality is it’s creating many more … if you have animals that breeders want to look after, and there’s an economic value to them, they’re going to breed more animals. And in turn that’s going to increase the population.

SS: And they’re going to fence more areas. 18% of South Africa today is privatized land. That’s the double of the parks! The parks make up 9-10& of the land, so suddenly we’ve created 30% of that land for animals. That’s a big deal! That influences more than hunting, by the way.

HtN: One final question. How did you two start working together as filmmakers? You’ve collaborated before, as well.

SS: So we’re also a couple…reveal, reveal…she hit on me…(laughs)

CC: (laughs) Not true!

SS: We’ve worked on a lot together, though we don’t work on everything together, and we also have a production company together. I think it was kind of a no-brainer, just because she entered the story from a different place: she understood it more, and I definitely wanted to go in and screw these people. And so it was this balance that got us in. And as you can tell from the film, we are huge fans of challenging our opinions and challenging others. So it helped that we didn’t start at the same place.

CC: Yeah, I agree with that. I think we came into this with two different perspectives, and I think it was good for our dynamic to be able to – while talking to other people and interviewing them – to be able to balance these perspectives. Maybe he felt one way and I felt another. I think he changed more over time.

SS: And it’s so hard to make a feature documentary – I don’t know if people realize how much it takes out of you – and it’s nice to have someone who cares as much … that you’re not alone, and so we like to be that partner for each other.

CC: I think, in the end, it becomes a better project.

HtN: Well thank you both. Thanks for taking the time to chat.

CC/SS: Thank you so much!

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)