WOJNAROWICZ

(Director Chris McKim’s fascinating documentary Wojnarowicz is available now on VOD via Kino Marquee. Like what you see here on Hammer to Nail? Why not give just $1.00 per month via Patreon to help keep us going?)

We all have experienced those moments at social gatherings in which attendees follow acceptable social norms, chitchat follows the conventional blueprint, everyone is guided by a delicate policy of politeness; but then, out of nowhere and not according to plan, a guest initiates conversation on a topic that makes others uncomfortable or is deemed politically “inappropriate.” As if following some social script, there is always that other guest that clumsily attempts to transition the conversation back to sterile niceties, or awkwardly raises their eyebrows once the disruptor leaves and announces to the group, “Alright then.” The US, for far too long, has attempted this same clumsy transition. When segments of the population bring up some of the most unsavory aspects of American history – racism, economic disparity, lack of adequate healthcare, a brutal foreign policy – a transition is initiated toward American Exceptionalism or “Freedom.”

Early in director Chris McKim’s (Freedia Got a Gun) documentary on the multimedia artist David Wojnarowicz we see a glaring example of these transitional sleights of hand in the form of phony local newscaster banter. The newscaster introduces a story about a Manhattan art exhibit losing federal NEA funding due to the display of artworks that combined the themes of politics with the AIDS epidemic destroying the LGBT community in the 80s. The newscaster wraps up the story with a transition toward a weather report: “This weather is certainly no work of art.” The sleight of hand is clear to those who are perceptive; you extinguish a social justice issue with a bland flame retardant – the weather report. David Wojnarowicz was uncompromising in his activist work and in the political themes contained in his art. His work, his personality, his unabashed queerness were overt declarations meant to expose America’s sleight of hand, its burying of injustice. Wojnarowicz would not quietly stand athwart as his friends and community died from government neglect during the height of the AIDS epidemic.

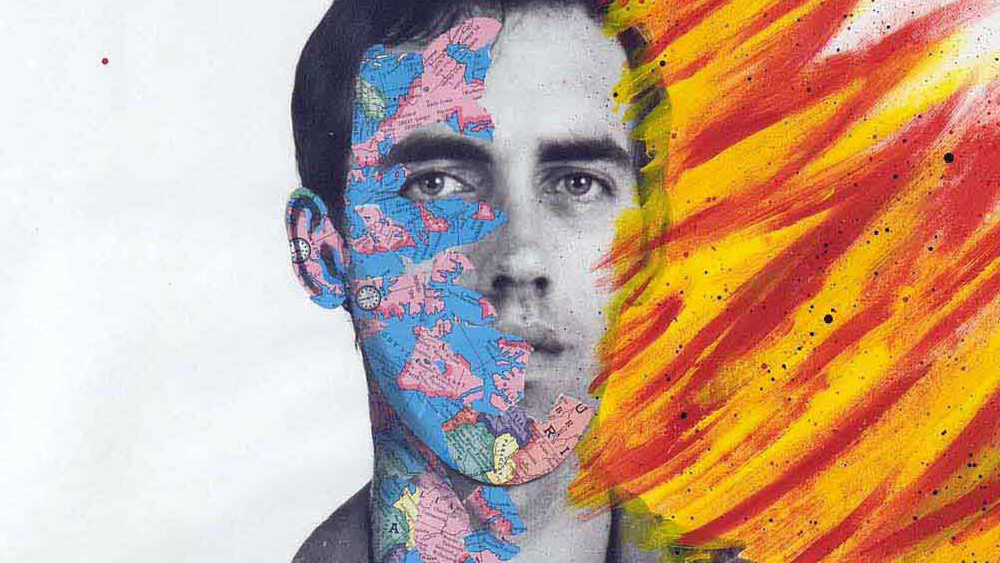

Wojnarowicz acquaints those not familiar with David Wojnarowicz’s multimedia career. McKim achieves a comprehensive narrative by using Wojnarowicz’s journal entries, cassette recordings, photos, and Super 8 films along with recollections given by his artworld friends. Wojnarowicz’s artistic path started when he discovered the poet Arthur Rimbaud and the writer Jean Genet. In fact, such was their influence that Wojnarowicz incorporated them into his visual art. In the case of Rimbaud, Wojnarowicz fashioned a paper Rimbaud mask. Some of Wojnarowicz’s most recognizable works are a series of photographs he took of himself in different gritty areas of New York City with the Rimbaud mask on. It was as if the photos were a sort of travelogue by which he was giving the ultimate nineteenth-century outsider poet, Rimbaud, a taste of New York’s season in hell – the crime-ridden, drug-infested New York City of the 80s. Ronald Reagan’s fantastical visions of “Morning in America” and “Make America Great Again” were contrasted with Wojnarowicz’s iconic stencil graffiti of houses on fire. Wojnarowicz was making it clear that if you bought into Reagan’s fantasy, you were going to be swallowed up by the flames of this new brutal rightwing surge.

McKim brilliantly places the viewer in Reagan-era New York City through the vehicle of Wojnarowicz. New York City was indeed the seedy cliché portrayed in movies like Taxi Driver. But it was also a place not completely taken over by suffocating corporate and real-estate interests. It was a place of opportunity. Wojnarowicz and the artists that made up The East Village Scene created their own space. If museums and galleries turned their noses up at the graffiti and stencil works of outsider artists like Wojnarowicz, these artists would create their own spaces – streets, walls, abandoned buildings and piers. Eventually the mainstream art establishment caught up to Wojnarowicz. New York Times Lifestyle magazine articles, gallery calls for solo exhibitions, and wealthy art buyers all started coming around looking for Wojnarowicz’s art. It was at this moment that Wojnarowicz truly developed his class consciousness. He realized that his outsider art was being bought and commissioned by Wall Street speculators that were thriving in Reagan’s America. If his art was being bought by the very wealthy individuals he abhorred, Wojnarowicz was going to make sure that they were going to buy the most subversive aspects of his aesthetic vision. He started giving his pieces names such as F—k You F-ggot F—ker and Prison Rape. If wealthy individuals like former treasury secretary Steve Mnuchin’s father were the buyers of Wojnarowicz’s pieces, Wojnarowicz was going to make sure his pieces were composed of found garbage and “looked like tetanus.” He would also see to it that they would have titles that made chitchats at wealthy soirees uncomfortable. Wojnarowicz was aware of what the commodification of art and the gallery system did to young talented artists like Basquiat. Wojnarowicz would not be squashed by the same pressures.

Wojnarowicz’s art was also a portal into his personal life. The fury his art expressed captured his experiences growing up with an abusive alcoholic father. Wojnarowicz experienced periods of homelessness. He went through a period of street hustling. When he finally met the love of his life, the photographer Peter Hujar, their love affair was cut short by Hujar’s death from AIDS. It was shortly after Hujar’s death that Wojnarowicz found out he also had AIDS.

After his AIDS diagnosis, Wojnarowicz developed an activist consciousness. His art would now “confront the state” and he realized that you could not “separate politics from AIDS.” He participated in Act Up protests, got arrested at some of those protests, and wrote an incendiary essay condemning Archbishop John O’Connor, conservative senator Jesse Helms, and The American Family Association. Wojnarowicz’s art was thrust into the culture wars of the late 80s and early 90s along with Andres Serrano and Robert Mapplethorpe. He was not going to turn the other cheek. He felt that these religious and conservative figures were emblematic of a life and death struggle, a struggle he was facing head on as AIDS destroyed him physically. These and other figures on the right were the same ones that refused to grant benefits or coverage of medical costs to those suffering from AIDS. Even obtaining help with rent payments was a struggle for those dying of AIDS. The government’s lack compassion for what was deemed a “gay plague” was for Wojnarowicz a call to “rise to greet the state, to confront the state” for the right to healthcare.

David Wojnarowicz died at the age of 37. Like him, many fathers, mothers, sons, friends, and gifted artists were silenced too soon by AIDS and government lethargy. The Covid pandemic has made voices like Wojnarowicz’s more relevant than ever. Wojnarowicz did not allow anyone to take him but not his art or vice-versa. He was his art. You had to take them both in all their glorious and sublime rage. Cheers to Chris McKim for his tribute to the beautiful soul that was David Wojnarowicz. Cheers to the ones that make a room uncomfortable. The world needs more disruptors of stiff dinner party conversation.

– Ray Lobo (@RayLobo13)