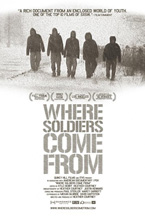

WHERE SOLDIERS COME FROM

(Where Soldiers Come From opens at Village East Cinemas in New York on September 9, 2011. For a full list of dates, visit the film’s official website.)

“You ever see that movie Deer Hunter?” asks a woman in Where Soldiers Come From; she’s speaking to the similarities between her son and his group of friends—all of whom have deployed to Afghanistan for nine months with the Michigan National Guard—and the cast of Michael Cimino’s Vietnam drama. The comparison is a good one: both groups consist of closely-knit, fraternal young men from working-class backgrounds (The Deer Hunter is set in a Pennsylvania steel town), both have few other options or prospects, and all are ultimately out of their depth. “I’ve lived here my whole life,” says one of the young men from Michigan’s Upper Peninsula about to depart; “I’m ready for a change.” This comes at quite a price, of course, and the initial mix of resignation, excitement, and even nonchalance with which the three young men at the center of Heather Courtney’s documentary start their journey gradually morphs into something else entirely.

The film’s title is a somewhat misleading one, as soldiers—like anyone else—clearly don’t come from any one place. Documentaries like this tend to focus on the economically downtrodden, which is too reductive and one-sided a view. That said, it would have been easy for Courtney to turn her film into a one-note tearjerker exploiting the story of these young soldiers and veterans, but she doesn’t. Though sensitive subject matter such as this seems to lend itself to an emotionally manipulative approach by its very nature as a heated, difficult issue, Courtney shies away from that. She adds no intertitles telegraphing our intended emotional response, nor does she or anyone else narrate. The stories told are the soldiers’ own, uninterrupted and seemingly unedited; the home-movie style footage comes across as genuine (and perhaps even necessary in terms of budget) rather than a put-on. (The abundance of Explosions in the Sky songs playing in the background, though probably inevitable at this point, might be a little much, however.)

At the center of the film are its cast’s contrasting internal and external responses to Afghanistan. Of the three, one nicknamed Bodi gets so many concussions that he’s no longer allowed on the IED-defusing excursions that injured him in the first place; it’s later revealed that he’s almost certainly endured a serious brain injury, and probably post-traumatic stress disorder as well. Their daunting job—clearing the roads of explosives in heavily-armored cars that can withstand the blasts so that the soldiers who go after them will be safe—begins to look rather Sisyphean: insurgents make and plant IEDs, American soldiers clear them, the insurgents make more, and so on and so forth. The picture that emerges from all this is of a zero-sum effort necessitated by the soldiers’ presence in the first place. The soldiers themselves note this, and it clearly wears on them. “I’m a racist American now because of this war…I didn’t really hate anybody until I joined the army,” says Bodi at the end of one rant. No one goes home at the end of this before-during-and-after portrayal of the soldiers’ experience without similar problems, but neither of Bodi’s two friends seem as negatively affected as he does.

At the center of the film are its cast’s contrasting internal and external responses to Afghanistan. Of the three, one nicknamed Bodi gets so many concussions that he’s no longer allowed on the IED-defusing excursions that injured him in the first place; it’s later revealed that he’s almost certainly endured a serious brain injury, and probably post-traumatic stress disorder as well. Their daunting job—clearing the roads of explosives in heavily-armored cars that can withstand the blasts so that the soldiers who go after them will be safe—begins to look rather Sisyphean: insurgents make and plant IEDs, American soldiers clear them, the insurgents make more, and so on and so forth. The picture that emerges from all this is of a zero-sum effort necessitated by the soldiers’ presence in the first place. The soldiers themselves note this, and it clearly wears on them. “I’m a racist American now because of this war…I didn’t really hate anybody until I joined the army,” says Bodi at the end of one rant. No one goes home at the end of this before-during-and-after portrayal of the soldiers’ experience without similar problems, but neither of Bodi’s two friends seem as negatively affected as he does.

Still, others in the company find themselves more compassionate and understanding of the Afghanis’ plight at the end of their deployment. This comes mostly as a result of interaction with the local children, whose unlikely smiles go a long way toward reminding the soldiers that they may, in fact, be there for a worthy cause. The fear of not actually doing any good, either for themselves or for the people of Afghanistan, weighs heavily on these men’s minds, and never fully diminishes. It’s a perpetual attempt at balance and considering things from the other side’s perspective; the ability of several of these men to do so even in the worst of times is impressive indeed. More than one express the desire and need to “do something” with their lives, but whether this is it is ultimately unknown, even (and especially) to them. At the end of their ordeal, the men of Where Soldiers Come From are left with a good amount of money and few marketable skills applicable to non-military institutions—in other words, their future is nearly as uncertain as it was before they left.

— Michael Nordine

Hunter67

Those guys do nothing. It’s a shame to the guys that have done something with their lives from that unit. Should be called

Where losers come from.