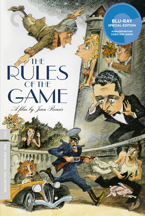

RULES OF THE GAME, THE

(The Rules of the Game was released in 1939 and is now available on Blu-ray through Criterion.)

When I first saw The Rules of the Game, I thought of it as a comedy that slowly morphed into a tragedy. Repeat viewings have altered this take: I now see that it’s tragic all along. Jean Renoir’s film certainly has its humorous elements, but they’re almost always tinged with sadness and used toward lamentable ends. This pattern begins early on, with the arrival in Paris of a man who’s just completed a solo flight across the Atlantic in order to impress a woman who isn’t there to greet him; much of what follows consists of similarly grand gestures ending in disappointment. Renoir treats the sorrow that accompanies these moments with a touch at once light but devastating, as though his characters’ ability to keep putting on happy faces when met with rejection of one kind or another is the surest sign they’re heartbroken. These men and women have conflicting agendas: everyone is after something (or, more accurately, someone), and their desires almost never align. When they do, it tends to be for brief, shining moments whose brevity only heightens the disappointment to follow.

Paved with good intentions, the film contains numerous romantic subplots—and enough infidelity to make Woody Allen blush—which start out innocently enough but gradually veer toward what Don DeLillo would call the deathward-leaning tendency of plots. The more elaborate and long-lasting a scheme is, the thought goes, the more likely it is to end in death. Such is absolutely the case in The Rules of the Game, and though there are laughs along the way, no one’s left smiling by its end. Women are trouble, men are instigators, and couples are constantly in flux. That it’s an excess of passion which renders so many incapable of keeping their romantic entanglements at bay tends to endear these characters to us, but retrospect makes it easy to see just how doomed they really are. Renoir’s scathing satire was released on the eve of World War II to a wholly unreceptive France, who either couldn’t tell what he was up to or, far more likely, saw all too clearly; this sad combination makes us think of these characters as teetering on an existential ledge without even knowing it.

Consider the hunting scene. All the men and women gathered at the country estate on which most of the film is set take their respective positions, get ready, and then spend an uncomfortably long time shooting at anything that moves—rabbits, birds, squirrels—until a winner is declared. In lingering on the image of just-shot animals several times, Renoir is foreshadowing more than he knows: several ways of life were eliminated in World War II, not just those satirized by his film. This predilection is hinted at in the title. Even the two world-changing wars The Rules of the Game was sandwiched between can be thought of as games with their own attendant rules; think of the Christmas truce, for instance. The film does, after all, play off the conventions of comedies of manners, and so the idea of both sticking to, and deviating from, accepted norms and mores is inherent in its formulation. There are certain things you can do and certain things you can’t—like carry on with another man’s wife. (But, if you must, then one way of doing so is more acceptable than another.) Rules imply consequences, and the repercussions on display here range from slaps on the wrist to expulsion to worse. Like those small, bothersome rabbits, the most serious transgressors are handled accordingly—whether by accident or fate. “I’m all for doing as I like, but etiquette is etiquette” says the impish Lisette, who herself is carrying on with another man. There’s constant chatter among both masters and servants as to who’s a real gentleman, who a lady; it matters not only how one presents oneself but that there’s inner-outer consistency. And there almost never is.

Consider the hunting scene. All the men and women gathered at the country estate on which most of the film is set take their respective positions, get ready, and then spend an uncomfortably long time shooting at anything that moves—rabbits, birds, squirrels—until a winner is declared. In lingering on the image of just-shot animals several times, Renoir is foreshadowing more than he knows: several ways of life were eliminated in World War II, not just those satirized by his film. This predilection is hinted at in the title. Even the two world-changing wars The Rules of the Game was sandwiched between can be thought of as games with their own attendant rules; think of the Christmas truce, for instance. The film does, after all, play off the conventions of comedies of manners, and so the idea of both sticking to, and deviating from, accepted norms and mores is inherent in its formulation. There are certain things you can do and certain things you can’t—like carry on with another man’s wife. (But, if you must, then one way of doing so is more acceptable than another.) Rules imply consequences, and the repercussions on display here range from slaps on the wrist to expulsion to worse. Like those small, bothersome rabbits, the most serious transgressors are handled accordingly—whether by accident or fate. “I’m all for doing as I like, but etiquette is etiquette” says the impish Lisette, who herself is carrying on with another man. There’s constant chatter among both masters and servants as to who’s a real gentleman, who a lady; it matters not only how one presents oneself but that there’s inner-outer consistency. And there almost never is.

The few characters who are actually honest in their romantic intentions, interestingly enough, tend to be single and openly pursuing someone who’s already spoken for: André, in love with the married Christine; mischievous Marceau, lusting after Lisette. It’s the ones pretending to be upright who end up doing the most harm. Renoir has much to say about surface appearances not matching the reality contained within—as well as the quibbles of the haves versus those of their servants—and he weaves the most biting elements into the more noticeable love stories so seamlessly that it’s easy not to notice they’re there. I’ve said the following here before, but it bears repeating: of the handful of films most often mentioned as being the best of all time—Casablanca, Gone with the Wind, Citizen Kane, and so on and so forth—Renoir’s has always struck me as the most poignant. It works as a comedy of manners, a satire, and a tale of several star-crossed lovers, all of whose inner lives prove strikingly complex. Renoir knows his characters are flawed, but he trusts in our ability to see past their shortcomings and focus on their (battered, broken, but still beating) hearts.

“It’s important to listen,” Christine says, but nearly everyone is too mired in their own scheming to heed her advice. Miscommunication is constant and often serves as either the source of problems or an exacerbating factor. This trope is as common in comedy as it is in tragedy and, on first viewing, it can be difficult to see which direction Renoir ultimately wants to take us. One could argue that The Rules of the Game vacillates between funny and sad, light and heavy, but it would be more accurate to say that it uses elements of comedy to enhance its tragedy. It just happens to do so in such a way that, by the time you’ve noticed, weeping seems even more pointless than laughing.

Audio/Visual: The transfer itself is exceptional, but, as with their original DVD release some years back, Criterion is working with imperfect source material here. The original negative was destroyed during World War II, and the reconstructed print used for this transfer was cobbled together from various sources. Though the quality of the image sometimes suffers as a result, there’s nevertheless a lot here to like: a clarity that was never reached on DVD, sharp contrast, rich (if sometimes overwhelming) shadows. The audio is particularly strong, with no noticeable instances of clicks or hisses. This is an especially talky affair, and we understand everything that’s being said even if none of the characters do.

Audio/Visual: The transfer itself is exceptional, but, as with their original DVD release some years back, Criterion is working with imperfect source material here. The original negative was destroyed during World War II, and the reconstructed print used for this transfer was cobbled together from various sources. Though the quality of the image sometimes suffers as a result, there’s nevertheless a lot here to like: a clarity that was never reached on DVD, sharp contrast, rich (if sometimes overwhelming) shadows. The audio is particularly strong, with no noticeable instances of clicks or hisses. This is an especially talky affair, and we understand everything that’s being said even if none of the characters do.

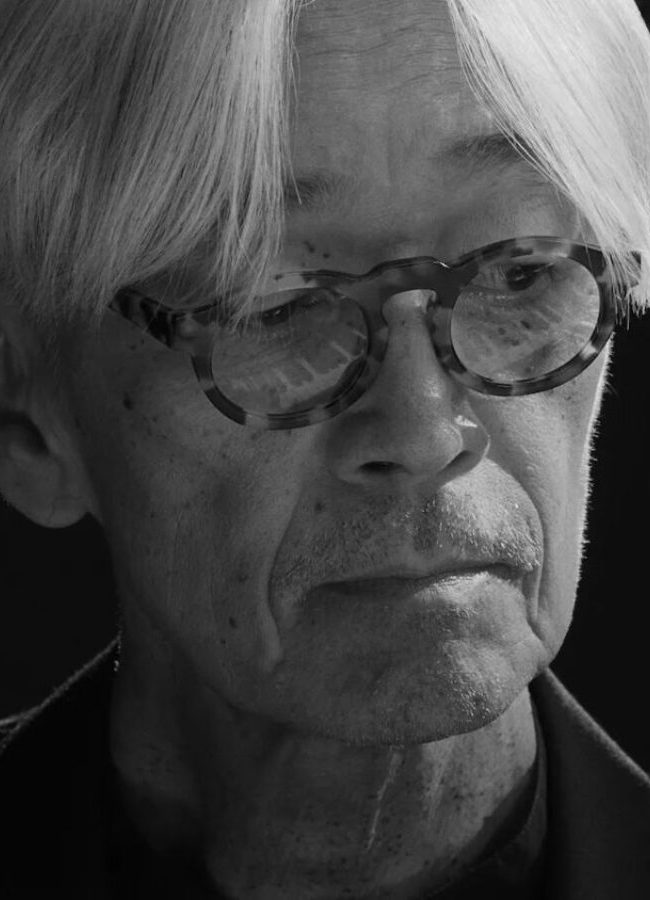

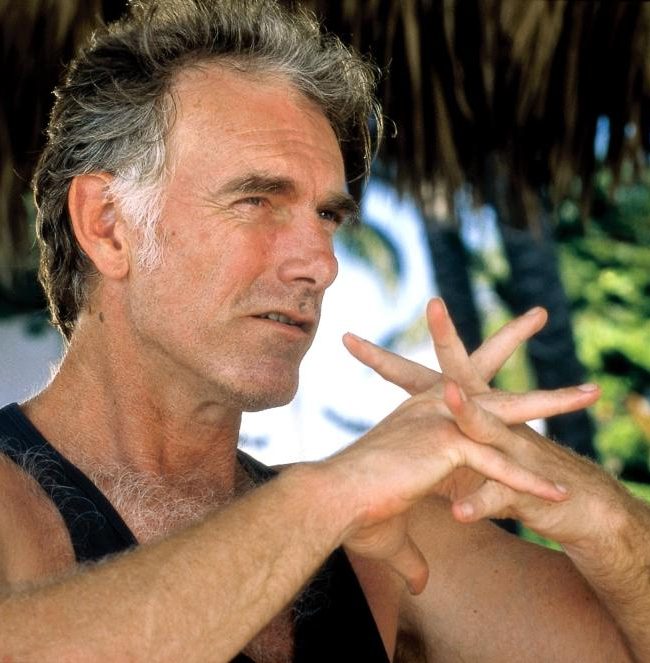

Supplements: Another expectedly excellent assortment. There are several mini-documentaries and behind-the-scenes featurettes, a seven-minute introduction from Renoir himself, scene analyses, interviews, commentary read by Peter Bogdanovich, and a breakdown of the different versions of the film. The quantity of these extras never comes as the expense of quality, with the pieces on/featuring Renoir being of special note. The Rules of the Game came at a singularly dark time, and Renoir’s insight into its production and reception is most fascinating.

— Michael Nordine