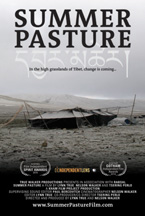

SUMMER PASTURE

(Summer Pasture makes its television debut on PBS’ Independent Lens on Thursday, May 10, 2012, and will be available to stream free online for one week after that. On May 10th, it also becomes available for rent and download at iTunes. Previous info: Summer Pasture was nominated for the Gotham Award for Best Film Not Playing At A Theater Near You 2010. It screened theatrically in New York City at the IFC Center—July 30-August 5, 2010—and Los Angeles at the Arclight Cinemas Hollywood—August 6-12—as part of IDA’s DocuWeeks 2010 program, which helps films qualify for end-of-the-year awards consideration. Visit the film’s official website to learn more. NOTE: This review was first published on August 2, 2010.)

To not confess upfront my predisposition to loving a film like Summer Pasture would be an unprofessional, irresponsible thing to (not) do. So there you have it. Yet in the case of this documentary by Lynn True, Nelson Walker, and Tsering Perlo, that personal bias is met with an equally hearty objective measure of appreciation. Summer Pasture is a loving, yet never fawning, portrait of a nomad family struggling to make ends meet in the downtrodden community of Dzachukha (Eastern Tibet, Sichuan Province, China). If the names Tulpan, Sweetgrass, Old Partner, and The Story of the Weeping Camel set your hearts aflutter, then get ready to be smitten once again.

Yama and Locho are a young couple with an adorable five-month-old daughter, whom they’ve nicknamed Jiatomah—“Pale Chubby Baby”!—until she receives her official name, yet Yama’s housework and Locho’s yak herding ensure that there is little time for rest and relaxation in this household. Still, they don’t whine about their daily routine. As many other herders have begun to abandon this difficult existence for a less taxing life in the city, Yama and Locho stand proud and firm in their decision to keep doing what they’re doing. As we hear them explain why this popular urban lifestyle is so worrisome to them, it becomes clear that they aren’t being stubborn about their situation; they are being practical, sensible, and grounded.

Yama and Locho are a young couple with an adorable five-month-old daughter, whom they’ve nicknamed Jiatomah—“Pale Chubby Baby”!—until she receives her official name, yet Yama’s housework and Locho’s yak herding ensure that there is little time for rest and relaxation in this household. Still, they don’t whine about their daily routine. As many other herders have begun to abandon this difficult existence for a less taxing life in the city, Yama and Locho stand proud and firm in their decision to keep doing what they’re doing. As we hear them explain why this popular urban lifestyle is so worrisome to them, it becomes clear that they aren’t being stubborn about their situation; they are being practical, sensible, and grounded.

Summer Pasture takes place during the summer of 2007, as Yama and Locho suffer through the ups and downs of living in such a gorgeous but harsh landscape, where clear blue skies give way to dramatic hailstorms in the blink of an eye, and where Locho’s precious yaks disappear on him on one troublesome occasion. As the filmmakers continue to shoot the couple going about their business, the talkative, charming Locho and the reserved, shy Yama gradually divulge their own personal history, revealing some unexpectedly moving secrets that complicate and further enrich their relationship. It is in these moments when Summer Pasture escapes any superficial trappings and becomes a fully realized, three-dimensional window into not just this world, but into the hearts and minds of these two noble souls.

While Summer Pasture qualifies as a work of ethnography, its overflowing humanity makes it something altogether more tender and sweet. However, the filmmakers never cross the line and overly sentimentalize, glamorize, or, on the other side of the spectrum, judge or look down upon their subjects. Instead, they simply reflect the natural rhythms of this world and the personalities of this good-natured couple. By showing what Yama and Locho’s everyday life is like and how this life—the only life they’ve ever known—is in danger of disappearing, the filmmakers have provided an even greater service than simply dignifying the life of one nomad couple. They have taught viewers a genuinely affecting lesson in humility, family pride, and personal responsibility.

— Michael Tully

Pingback: Best Film Not Playing At A Theater Near You 2010 – Hammer to Nail

Pingback: 2011 SPIRIT AWARDS PRIMER – Hammer to Nail