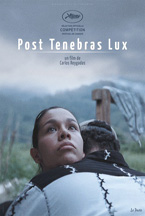

POST TENEBRAS LUX

(Post Tenebras Lux is distributed by Strand Releasing and is now available on DVD. It opened theatrically at the Film Forum on Wednesday, May 1, 2013. It world premiered at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival. NOTE: This review was first published at Hammer to Nail on September 14, 2012, in conjunction with its North American premiere at the 2012 Toronto International Film Festival and also as a “Pick of the Week” for Filmmaker Magazine on Thursday, May 2, 2013. )

Carlos Reygadas’ Post Tenebras Lux is a landscape of possibility, vibrantly alert to the tensions of class, family and desire, pulsating with life. The story of a wealthy family living in the secluded Mexican woodlands, the film takes on the issues of duty, class and morality with a feverish poetry from its opening sequence to its radical conclusion. The film begins with a dream; Rut (Rut Reygadas) is a toddler racing through a rain flooded field, thrilling to the interplay between a herd of horses, a team of cattle and a pack of dogs. Unsupervised by adults, Rut’s freedom soon becomes terrifying as night falls and a storm approaches, leaving her abandoned to darkness, with lightning tearing at the sky. “Mama…,” she calls. Thunder responds.

Post Tenebras Lux soon begins to hop from poetic representation to the lived experience of the entire family, cutting between incidents in the waking world and the possibilities of what might be. Although the film’s opening seems to be a representation of Rut’s dreams– her mother asks her if she has been dreaming about animals? ‘Yes,” she replies. ‘Which ones? Cows?,’ her mother asks her. ‘Giraffes,’ she says.– Reygadas seems to be drawing not on the loaded interpretation of dreams as we understand them in a Freudian sense, this symbolic substance that demands interpretation, but on poetry, inquiring as to whether cinema can provide a poetic representation of life without the interpretive baggage. Film itself is so conditioned by the framework of interpretation that even humble attempts to radicalize the relationship between images and narrative can feel deeply threatening, but this is no humble attempt; Reygadas seems hell-bent on reforming that relationship from whole cloth.

Post Tenebras Lux soon begins to hop from poetic representation to the lived experience of the entire family, cutting between incidents in the waking world and the possibilities of what might be. Although the film’s opening seems to be a representation of Rut’s dreams– her mother asks her if she has been dreaming about animals? ‘Yes,” she replies. ‘Which ones? Cows?,’ her mother asks her. ‘Giraffes,’ she says.– Reygadas seems to be drawing not on the loaded interpretation of dreams as we understand them in a Freudian sense, this symbolic substance that demands interpretation, but on poetry, inquiring as to whether cinema can provide a poetic representation of life without the interpretive baggage. Film itself is so conditioned by the framework of interpretation that even humble attempts to radicalize the relationship between images and narrative can feel deeply threatening, but this is no humble attempt; Reygadas seems hell-bent on reforming that relationship from whole cloth.

After opening with Rut’s “dream”, Reygadas lays it all on the line; a door opens, and a satyr, made of pure red light, enters the main living area of a house and begins exploring the space, when he is seen by a little boy and ducks into an undisclosed room. Has the devil arrived? Have we landed in yet another dream? Is this the chupacabra, the mythical Mexican cryptid come to wreak havoc on what appears to be a farm? Is this a symbolic harbinger of bad things to come? Has he arrived to herald the loss of the girl? Can it be all of these things at once? It seems beyond the point; within the context of the moment, it is thrillingly perverse and unequivocal in its power as an image. The sequence itself is incredibly simple, and yet it explodes with possibility; no alarm is raised, no cries from any of the rooms, as if this was all expected.

A few scenes later, as the family gathers for breakfast, Juan (Adolfo Jiménez Castro), the father of family retreats to the deck to take in some fresh air when he discovers that one of the family’s many dogs has been disobedient, and he proceeds to brutalize the animal in a fit of rage before his wife Natalia (Nathalia Acevedo) almost passively asks him to stop. Here again, Reygadas lays out yet another tension that runs throughout the film, that of the perversion of male aggression against the natural world; dogs are constantly being kicked and beaten (and, at one point, run over by a truck without a second thought), ancient trees are cut down and destroyed by petty egoists and this corruption of values, the trickle down of misery, runs rampant throughout the social context of the film. It all comes to a head in a violent scene that reframes the entire movie, forcing a reinterpretation of the film’s chronology and structure, and sending the movie spiraling toward its spectacularly powerful conclusion which, instead of spoiling here, I will spoil here*. I suggest seeing the film before reading that footnote.

What the violence in the film serves to do is further mark the degradation of surface appearances, of the “order of things”, and Reygadas is extremely effective in using pitch black satire to underline the corruption of the social order. One scene, a visit to an underground sex club in which the rooms are named after philosophers (you have to enter the Hegel room to find the Duchamp room), could be read as a surreal excursion into the sexual values of the upper class, but, in retrospect, it can also be seen as a desperate cry for intimacy after a terrible loss, a search for the comforts of some kind of real, tangible pleasure in a world emptied of it. Another great scene in the film takes place at a rural meeting of Alcoholics Anonymous, where one character’s economic success is described in terms most valued by the laborers who make up the audience; a litany of the high-quality materials used in his home’s plumbing system.

It is not in the least bit difficult to see what Reygadas is getting at here and careful, patient viewers will be rewarded with a visual and thematic consistency that lends real power to the images and the story which is, ultimately, quite a simple tale. What is not simple is the position of the viewer in the film, forced by desire and habit into a constant evaluation of the film’s meaning and structure, but left to contemplate its images on Reygadas’ terms. Thrilling.

— Tom Hall

*Spoiler: In the film’s penultimate sequence, Siete (Willebaldo Torres), a laborer who has worked on Juan’s house and has murdered Juan after being discovered robbing the family’s expensive home, returns to his own family to discover his wife and children have abandoned him. Destroyed by guilt, he walks into an empty field situated in a beautiful valley and, in a single motion and using his bare hands, tears his own head off clean at the neck. The sky begins to rain blood and the cows arrive to drink it. Soon, the field is flooded and we know it is the same field, the same puddles, where Rut’s dream, which began the film, was situated.

BrazilianBear

Very nice review. Keep up with the good work.

Pingback: HOME VIDEO PICKS – Hammer to Nail