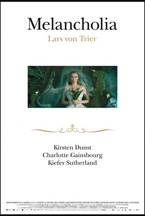

(Melancholia is now available on DVD and Blu-ray through Magnolia Pictures, as well as at Amazon Instant. It world premiered at Cannes 2011, where Kirsten Dunst won the Best Actress award and Lars von Trier was declared “persona non grata” for being Lars von Trier. After an unexpected one-week run in Los Angeles that started on July 22nd, it’s being more widely released by Magnolia Pictures later this year.)

In the week that’s passed since I saw Melancholia, I’ve found myself not thinking about Melancholia very often. And it isn’t because I disliked Lars von Trier’s depression-as-apocalypse vision of the end of one woman’s world; on the contrary, I was often quite moved by it. When I call to mind certain details and scenes, it’s usually fondly and always in awe of the visual panache with which each and every moment was executed. The problem, then, is that these recollections never come on their own: I have to go searching for them. All the elements are there, but they don’t mesh as well as they could and should. There’s little connective tissue between them, and so the film’s strongest, most beautiful moments are separated from each other like stars.

But oh, those moments: Melancholia is arrestingly rendered from first frame to last, nowhere more so than in its opening montage. Here the end of the world is personal first, planetary second, and seamlessly woven together in breathtaking fashion. What happens after that doesn’t always sustain the same visual and thematic concision (how could it?) and may be viewed in one of two ways: as von Trier shrinking a cosmic event down to the size of one woman’s depression or as him ballooning that depression into a cosmic event of its own. (Or is it both?) As a portrait of self-destructive despondency and the inability—or perhaps even unwillingness—to help oneself, it’s pitch-perfect. Kirsten Dunst is distant, often unlikeable, and rarely dependent on more than her hauntingly expressive face in mournfully conveying Justine’s permeating grief. (Von Trier’s own struggles with depression are fairly well-known at this point and I won’t attempt to psychoanalyze the Danish auteur, but it seems reasonable to assume that the Dunst character is at least based in part on his own life.) Her emotions, which she likens to vines and roots dragging her to the ground as she tries to free herself in vain, are felt all the more heavily in light of the fact that we’re given no sense of the outside world’s reaction: Melancholia is a closed system, solely concerned with how its literally earth-shattering events affect its small cast of central characters.

“I just have one thing to say: enjoy it while it lasts,” Justine’s mother says to her at her wedding; clearly the implications extend beyond marital concerns. Dunst is wonderfully engaging even when she’s detached—and, what’s more, brilliant in subtly showing the ways in which someone as fundamentally unhappy as Justine has to wear two faces throughout the day: one for herself, and one for those from whom she needs or wants to hide her true self—but the film’s second half, which sets its gaze on her older, more stable sister, is to my mind the more compelling of the two. Charlotte Gainsbourg, as Claire, is delicate yet magnetic; the only one who seems truly bothered by the prospect of Earth colliding with Melancholia, she grants the film an otherwise-lacking emotional core to revolve around. She’s terrified where Justine is blasé, and is in some ways the only character who might be thought of as a victim here. There’s nevertheless a certain flatness to the apocalyptic proceedings where there should be a suffocating density instead; Melancholia aims to be both sweeping and intimate, but lands somewhere in between.

“I just have one thing to say: enjoy it while it lasts,” Justine’s mother says to her at her wedding; clearly the implications extend beyond marital concerns. Dunst is wonderfully engaging even when she’s detached—and, what’s more, brilliant in subtly showing the ways in which someone as fundamentally unhappy as Justine has to wear two faces throughout the day: one for herself, and one for those from whom she needs or wants to hide her true self—but the film’s second half, which sets its gaze on her older, more stable sister, is to my mind the more compelling of the two. Charlotte Gainsbourg, as Claire, is delicate yet magnetic; the only one who seems truly bothered by the prospect of Earth colliding with Melancholia, she grants the film an otherwise-lacking emotional core to revolve around. She’s terrified where Justine is blasé, and is in some ways the only character who might be thought of as a victim here. There’s nevertheless a certain flatness to the apocalyptic proceedings where there should be a suffocating density instead; Melancholia aims to be both sweeping and intimate, but lands somewhere in between.

The film may be seen as one heavenly (or hellish, depending on how you look at it) body belong to a constellation of no fewer than three other films released this year: Nostalgia for the Light, which searches underground for the still-unclaimed bodies of countless victims of the Pinochet regime while simultaneously gazing into the night sky from Chile’s Atacama Desert; Another Earth, which, much like von Trier’s film, concerns a previously-undiscovered planet in extremely close proximity to our own; and The Tree of Life, whose astral chart is of the beginning of the world rather than its end. These celestial underpinnings are for von Trier a means of portraying the futility of human aspirations in the face of the indifference—and, indeed, hostility—of the cosmos, as well as the launching point for an experiential take on our relation to the world. “Life is only on earth,” Justine says, “and not for long.” To think otherwise in the context of von Trier’s film is foolish.

Writing this review has been strange in that, though I liked Melancholia, I mostly find myself able to focus on its shortcomings. Perhaps this is a sort of praise in and of itself, however, as it speaks to how much I expected of it and the fact that its best qualities, like Melancholia itself, are visible to the naked eye. Call it poor expectation management—my hopes were high indeed, especially after Antichrist—if you like, but ultimately this is a film I admire more than I adore. Regardless, allow me to end by saying that I reserve the right to alter or even reverse some of my judgements of the film upon seeing it again later this year. I only fear that simply wanting that to happen won’t be enough to make it so.

— Michael Nordine

Bail Bonds Los Angeles

Bail Bonds Los Angeles…

[…]right here are some listings to online websites we connect to as we feel these are definitely worth browsing[…]…

Pingback: VOD PICKS – Hammer to Nail

Pingback: PERFECT SENSE – Hammer to Nail

Pingback: HOME VIDEO PICKS – Hammer to Nail

Pingback: HOME VIDEO PICKS – Hammer to Nail