In 1967, Melvin Van Peebles became the first African-American to direct a narrative feature film in twenty years, following DIY pioneer Oscar Micheaux’s final film, The Betrayal, with his Story of a 3-Day Pass (La Permission). Ironically, this stretch of time coincides with the era of studio decline that followed Hollywood’s golden years, starting roughly with the Paramount case in ‘48, which stopped the vertical integration of the movie studios, followed by the threat of television in the ‘50s, and ending with the emergence of the New Hollywood in the late ‘60s. The bigger, perhaps sadder irony is that this particular American black man had to go to France to become a movie director, using sheer guile and determination to tell a story that, while set among the French, takes on the anxieties of mid-20th Century American blackness with insight, humor, and genuine feeling.

Harry Baird, tall and stark, in turns morose and goofy looking, is Turner, a black American GI stationed in France. When we meet him, during the jazzy credit sequence that is the first of many indicators of this film’s debt to the waning French New Wave, he is the only remaining soldier in the barracks awaiting leave. He’s given a stern talking to by his commander, who reminds him of how they expect a colored soldier to behave on leave (i.e. no miscegenation) and is wearily given his three day weekend away from the army base.

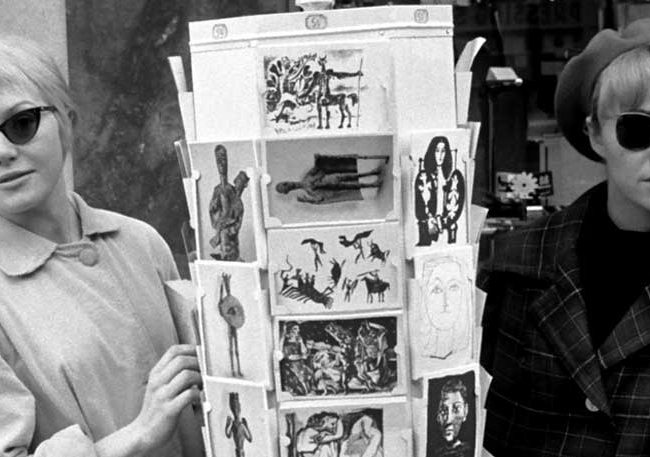

Turner strolls the streets of Paris, battling the persistent loneliness and otherness that comes with the territory, venturing into bars and imagining the acceptance of any number of young women. He meets Miriam (Nicole Berger), a level-headed Parisian who seems to be all quick smiles and is willing to listen to and dance with Turner. A delicate courtship begins, one that quickly draws the ire of Turner’s fellow American soldiers on leave, locals familiar with Miriam and others unaccustomed to and hostile toward the presence of Negroes.

Story of a 3-Day Pass is Van Peebles’ most stylistically assured and emotionally satisfying film. There is a joy in the freewheeling aesthetic conceits. He unpacks scenes using highly subjective techniques like split-screen, subject-on-dolly moves, freeze frames, abrasive, looping musical interludes, and extended POV shots, allowing us to enter the world of Turner in a way he never again explored with such elegance. Relying heavily on direct address to the camera, Van Peebles finds a nice analog to the black suspicion of the white gaze—we constantly inhabit Turner’s perspective as people talk to him.

Story of a 3-Day Pass is Van Peebles’ most stylistically assured and emotionally satisfying film. There is a joy in the freewheeling aesthetic conceits. He unpacks scenes using highly subjective techniques like split-screen, subject-on-dolly moves, freeze frames, abrasive, looping musical interludes, and extended POV shots, allowing us to enter the world of Turner in a way he never again explored with such elegance. Relying heavily on direct address to the camera, Van Peebles finds a nice analog to the black suspicion of the white gaze—we constantly inhabit Turner’s perspective as people talk to him.

Van Peebles arrived in France in the early part of the decade, as the New Wave’s seminal films were finding their way to French audiences and around the world. One cannot understate the influence of those films on this picture (Nicole Berger, who died in a tragic car accident shortly after wrapping La Permission, plays Charles Aznavour’s suicidal wife in Shoot the Piano Player). But, as with Watermelon Man, in which he takes on the aesthetic (if not the thematic) characteristics of a mainstream American studio comedy, as well as Sweetback, in which the New American Cinema and Los Angeles Psychedelia of the late ‘60s are defining influences, Van Peebles proves with his first feature that he has always been a chameleon director, ever changing, never static in his approach nor afraid of a fight.

— Brandon Harris

(Story of a 3-Day Pass (La Permission) screens on Saturday, December 6th at 3pm at MoMA as part of the “Melvin Van Peebles: A Salute From MoMA and IFP” tribute. Or you can buy it at Amazon.)