EARLY SHORT FILMS OF THE FRENCH NEW WAVE

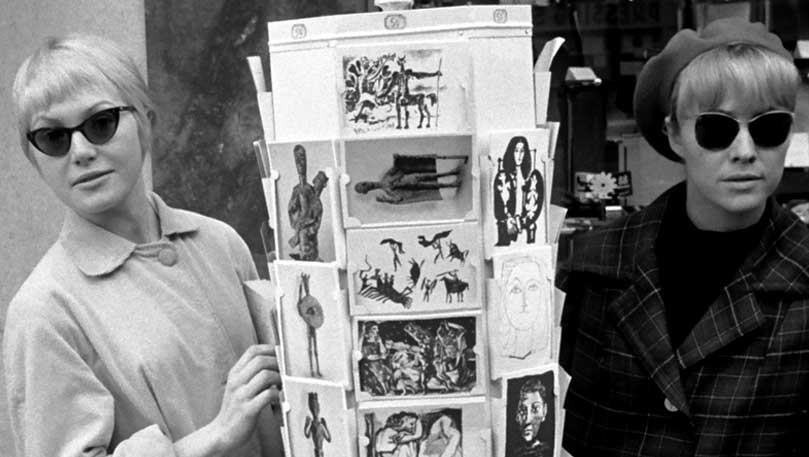

With the passing of Agnès Varda and Jean-Luc Godard within the last half-decade and last year, respectively, renewed attention has justifiably returned to the beginnings of the so-called French “Nouvelle Vague” (or “New Wave” in English; “Bossa nova” in Portuguese; “Nūberu bāgu” in Japanese). Whereas their Cléo de 5 à 7 [Cléo from 5 to 7] (1962) and À bout de souffle [Breathless] (1960) are relatively accessible and comparatively well-known (along with many of the other remarkable films associated with the movement) and books such as Richard Brody’s Everything is Cinema illuminate the period in magnificent detail, where does one go to view the humble beginnings which predate these established classics?

Granted, developments against the norm within the film industry were not solely a French phenomenon. Such a “wave” crested throughout the world: Australia, Japan, Iran, Germany (where it was known as Neuer Deutscher Film / New German Cinema), Mexico, Thailand, India, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Czechia (with films from this Eastern European component a particular favourite, admittedly). It wasn’t long before these trends dominated the music business as well, with Neue Deutsche Welle / New German Wave in the late-1970s and the inevitable New Wave of the early-1980s in North America.

Availability of these nascent Nouvelle Vague shorts has generally been limited to poor bootlegged transfers on illegitimate or quasi-legitimised streaming sites or, immensely preferable, as extras on a number of Criterion Collection releases (notably Antoine et Colette (1962) in their essential Antoine Doinel set). Icarus Films has thankfully remedied this situation by pulling together a Blu-ray collection of highlights entitled Early Short Films of the French New Wave which, true to its name, includes many formative-efforts from the represented filmmakers while straying into the end of the era with a few lesser-known (yet similarly talented) directors.

If not for the Cinémathèque Française, co-founded by filmmaker Georges Franju and cinéaste Henri Langlois in the mid-1930s, an ideal gathering-place for French film-enthusiasts might not have existed (although, presumably, these assorted individuals would’ve found each other at another of the many Ciné-Clubs in Paris at the time). Furthermore, if a number of these future-filmmakers had not found their critical voices writing for Cahiers du cinema, debating the “tradition de qualité” [“tradition of quality”] which they believed to disregard the need for new pathways in cinematic storytelling, a boilerplate for an alternative might’ve never taken root.

In a sense, it was François Truffaut’s Une certaine tendance du cinema français printed in the pages of that publication which pointed a way forward. The first in the Early Short Films… collection was completed two years later: Alain Resnais’ Toute la mémoire du monde [All the World’s Memory] (1956). [Icarus previously released a set of five Resnais shorts, of which this and Le chant du Styrène (1957) were included. The latter is among the most spectacular documentary films ever produced, with an Oulipian text written by Raymond Queneau and an inventive score from Pierre Barbaud.] The rest of the collection follows a chronological sequence with shorts by the aforementioned Agnès Varda, Jacques Rivette, Jeanne Barbillon, Jacques Doniol-Valcroze, Guy Gilles, Gisèle Braunberger, Melvin Van Peebles, a pair from Maurice Pialat, another two by Jean Rouch, three by François Reichenbach and a trio by way of Jean-Luc Godard (including a collaboration with François Truffaut—Une histoire d’eau [A Story of Water] (1958)—in his sole appearance on the set). Many (if not most) of those names should be familiar although a few might be curious. Melvin Van Peebles? Indeed, he made Les cinq cent balles [500 Francs] (1961) while in France although it is a stretch to add him amongst the individuals associated with the French New Wave. The inclusion of Jeanne Barbillon and Gisèle Braunberger, while most welcome, also extends the boundaries of those regularly grouped with the self-anointed movement (yet it is rather ideal to have more than Varda as female representatives in these selections). While they are latecomers to the group, their contributions (which largely close-out the disc with a Jean Rouch essay-film featuring Maurice Pialat in-between) are grand additions. What of Jacques Doniol-Valcroze? Co-founder of Cahiers du cinema, of course, and its editor throughout much of the 1950s. Not quite as known for his film-work but this might change that. As for François Reichenbach, with as many films here as JLG, if his name isn’t immediately familiar, he is potentially best-known as co-director of F for Fake (1973) with Orson Welles and Chris Marker’s Le sixième face du pentagone [The Sixth Side of the Pentagon] (1968) (along with the stunning Scopitone of Serge Gainsbourg and Brigitte Bardot performing “Bonnie and Clyde”). Guy Gilles? An assistant to François Reichenbach shortly after his arrival in Paris, albeit with an impressive filmography of his own prior-to and thereafter.

While not exclusively within the realm of the New Wave, what other characteristic do these shorts share? They were all produced by the influential Pierre Braunberger. Without his exceptional efforts, the history of French cinema might’ve taken a considerably different course. His encouragement (and investment) allowed several of these ‘makers to make the jump into filmmaking. Within these Braunberger-centric parameters as a guide, however, it leaves aside the other Cahiers du cinema-related New Wavers (such as Claude Chabrol and Éric Rohmer) and associated Left Bank writer / directors (Alain Robbe-Grillet, Marguerite Duras and Jean-Pierre Melville, among others, although none of these, outside of the latter, strayed much beyond the feature-length and Melville’s only short—24 heures de la vie d’un clown [24 Hours in the Life of a Clown] (1946)—long-predates the existence of the Nouvelle Vague). Those assorted absences leave room for optimal insertions, particularly the set-closing Directing Actors by Jean Renoir (1968) which, despite the title, is directed by Braunberger’s wife, Gisèle. As parameters go, these seem to be worthwhile variations-on-a-theme, indeed.

If we have effectively passed through the trough of this wave (if the metaphor is not completely depleted), perhaps the time has arrived for another cresting, here and elsewhere. The Icarus collection makes the case for the ample benefits of revisiting these historically- and, in most cases, artistically-significant works again and again, repeatedly or, for some, for the first time.

EARLY SHORT FILMS OF THE FRENCH NEW WAVE (1956 – 1968)

dir. [various] [roughly 360min.] Icarus Films / Les films du jeudi / CNC

— Jonathan Marlow (@aliasMarlow)