ON THE FRINGE, PART SIX: GAS, FOOD LODGING (1992)

Allison Anders’ sophomore feature Gas, Food Lodging is an aspirational film about fantasy. It is in many ways an antithesis of the kind of movies I’ve been chronicling and will continue to discuss with my “On the Fringe” series.

Allison Anders’ sophomore feature Gas, Food Lodging is an aspirational film about fantasy. It is in many ways an antithesis of the kind of movies I’ve been chronicling and will continue to discuss with my “On the Fringe” series.

Gas, Food Lodging is in fact an ideal case study of the kind of films I believe many of the pictures on my list are countering by measure of their unadulterated authenticity, minimalistic aesthetic and, for the most part, explicitly anti-Hollywood tendencies.

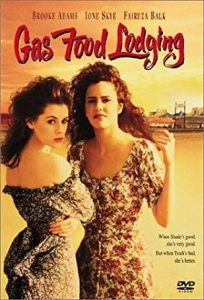

The stunning actresses portraying the principal focus of the film – Ione Skye as older sister troublemaker Trudi and the young, (very) wide-eyed, doll-like Fairuza Balk (best not to think of her here as the goth icon she would later become in such films as The Craft) – are truly…well, quite stunning.

They’re fine actresses (in this film and others) along with the rest of the cast, which includes a rough-and-tumble, whiskey-throated, cowboy hat-wearing James Brolin.

And yet, it’s distracting: They’re all a little too good-looking to be portraying the lost souls of their characters stranded in a New Mexico trailer park bordered by only a tiny, nearly dead main street and truck stop diner (from which the film takes its name and where work both Trudi and mother Nora – played skillfully by Brooke Adams, who once again appears a little too pretty to be a longtime truck stop waitress working double shifts and raising two feisty daughters on her own).

No one in Gas, Food Lodging, but for a few background characters, has even the slightest soupçon of a drippy-drawly southwestern accent.

Comics guru Scott McCloud refers to this trick as “masking.” A more familiar, easier-to-watch and easier-to-identify-with protagonist – perhaps more of an abstraction in the case of simple, cartoonish stick-figure-like Calvin from Calvin and Hobbes being placed against a lush, photorealist backdrop – is used to help the audience find an accessible entryway into what would otherwise be a more exotic (and genuine) environment.

This allows the viewer to believe in the characters — even if s/he knows in his/her heart of hearts said characters are rather inauthentic. Because, hey, they’re set against a fairly authentic background that we, the general public who may not have a drippy-drawly southwestern accent, can explore “safely” and easily. (This grants the filmmakers/studio/etc. the added bonus of having bankable, familiar actors on their movie poster.)

Sean Penn has a terrific speech about the same in a memorable scene from 1998’s Hurlyburly. Penn, as casting producer Eddie, upbraids friend and aspiring actor Chazz Palminteri’s Phil for believing he’ll ever one day become a leading man, when in fact — due to his heavy Brooklyn accent and rougher mien – he’ll forever be relegated to “background,” with the sole value of making the rest of the movie he might be in and the actual leading men and women therein appear that much more realistic by matter of having “real” tough guys such as himself supporting them.

Beyond the perfect complexion of its cast we’re expected to believe would have no money for makeup, facials, professional hair styling or financial ability for such trendy regalia, everything in Gas, Food Lodging is also far too clean for an impecunious, dusty truck stop town.

The dialogue, though fairly well-written and at times introspective, funny and even insightful, can also come off as histrionic and theatrical (and not merely in scenes of great strife or argument, a la, say, every time hell-raiser Trudi and harried mother Nora butt heads).

The dialogue, though fairly well-written and at times introspective, funny and even insightful, can also come off as histrionic and theatrical (and not merely in scenes of great strife or argument, a la, say, every time hell-raiser Trudi and harried mother Nora butt heads).

Strange twists of unrealistic serendipity abound that seem more in aid of efficiently and easily moving the plot along than they do of organically popping up in what would otherwise be a realistic portrayal of its characters and the circumstances in which they find themselves.

Simply put, Gas, Food Lodging comes off as less of a depiction of reality as it does a film at best … and television at worst.

So, why include Gas, Food Lodging in the list of “On the Fringe” films? Simply, as the (now) old joke goes: “Hey, it’s the nineties.”

To better understand what I mean here in taking this silly adage seriously, we must first acknowledge that, to filmmaker Allison Anders’ credit, Gas, Food Lodging is – once more – a film very much about fantasy.

Balk’s Shade opens the film with her ongoing voice-over explaining how relieved and at ease she is whenever a woman named Elvia Rivero comes to town … only to quickly reveal (as we see in similar subsequent scenes) that Rivero is in fact an old Mexican actress from a series of black-and-white, silent movies that Shade watches over and over again at a small, rundown movie theater in town.

Right from the start, then, we are to regard Gas, Food Lodging as a film about such blurs between fantasy and reality; indeed, some of the most emotional moments in the film have Shade tearing up at watching her (likely long-dead) screen idol on screen.

Shade concurrently works toward another (quite childlike) fantasy of seeking out a new man to replace the father who left so many years ago, more for her mother Nora than for herself. Nora (whose name can’t be disassociated in the minds of the initiated viewer from Ibsen’s appropos A Doll’s House) meanwhile allows herself to be enveloped in her own fantasy of a man who seems to check every box for optimal eligible bachelors…except for the fact that this rowdy cowboy is not a bachelor at all.

Trudi is the most racked by her fantastical urges in wanting to escape from town altogether (to become a model? an actress? the life partner of some exciting and debonair gentleman caller mystically personified by a British rock-hound adventurer she encounters at one point?).

She also has the tendency of getting herself in trouble (both metaphorically and literally) by indulging in the fantasy found in a variety of other men of whom she runs afoul, trying to make herself believe that this time things will be different, this time, the guy really loves her and not just her body and self-confessedly loose morals.

References about how the characters in the film are led – often quite forcefully – by their dreams abound in Gas, Food Lodging. Aside from Shade’s obsession with Rivero onscreen, she at one point is dressed up by older sister Trudi to appear as a kind of Olivia Newton-John pin-up in a doomed-to-failure attempt at winning the affection of a boy in town who is himself wrapped up in his own fantasy of the actual Olivia Newton-John.

Shade is later told by a factotum Mexican boy named Javier who skips around from job to job (including one as a less-than-skilled projectionist at the theater Shade frequently haunts): “Hey, movie girl! No matinees today, huh? Just real life.”

There’s even a very direct underpinning of fantasy involving the promise of the easy escape that comes with cable television, when Nora is hectored into a developing relationship with a cable TV man named – appropriately – Hamlet, namesake of one of literature’s most self-deluded characters.

The film is told, after all, predominantly through the eyes and voice-over of a young teenage girl (Shade), as per its original text, a young adult novel entitled Don’t Look and It Won’t Hurt. We have here, then, a narrator who is still trying to understand who she is, what she is and what life itself is actually all about, wobbly propped up by (often misguided) advice from the various characters who populate her cloistered and cramped universe.

Of course, then, fantasy would be a major force not only in the storytelling but format and structure of the filmmaking itself. (I liken this to the clearest defense against those who would critique Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street as being too long, gratuitously graphic in language/eroticism/drug-taking etc. and too glorifying of decadence overall … when of course this should be how the film was made, as it’s an exegesis of unhampered decadence itself!).

Sure, there are some admirable attempts at “genuine” moments in Gas, Food Lodging by its more than capable director at the helm. Arguments between Trudi and Nora keep awake Shade in her tiny bedroom, reminding us of the fundamental reality of noise control (or lack thereof) in a crowded trailer.

A rather light and funny scene takes place involving Nora on the toilet in the bathroom yelling out at her daughters about the fact that there are no more tampons left and that they should know better than to not replace them when the box is empty.

A wonderful scene involving Javier taking care of and dancing with his deaf mother while Shade watches comes off as needfully unsentimental and joyful, as opposed to aggressively pulling of heart strings and overly sympathetic.

The very fact that Anders focuses on extra-small town America for the proscenium of her film is of crucial note here, as well. Consider how uncommon it was in the late eighties and early nineties to see such subject matter on the big (or small) screen.

Along with television’s original run of Roseanne, Harmony Korine’s 1997 directorial debut Gummo and perhaps 1993’s What’s Eating Gilbert Grape? (another film that mixes many admirably genuine moments, fine acting and slice-of-life narrative from a tiny flyover state town…with obvious allusions to fantasy and a slightly unbelievably gorgeous, unchiseled cast), Gas, Food Lodging was a rare treat of smalltown representations onscreen at this time in our nation’s history.

Anders is a director clearly in touch with her sense of portraying a fantasy-tinged reality.

She would shortly after this film become one of the early directors of Sex and the City, a series similarly at once vying for a certain truth and reality in the journeys of four women coping with the unmerciful vicissitudes of getting older, nebulous dynamics of relationships (both friendships and love affairs) and surviving in “the big city”…while unabashedly reveling in obvious fantasy aspiration (one of the principal characters being named, simply, “Mr. Big”/protagonist Carrie’s never really needing to worry about money as a relatively small-time weekly columnist for a medium-tiered newspaper in one of the most expensive cities the world over, etc. etc.).

Anders would in fact even sooner still after Gas, Food Lodging become one of the four up-and-coming filmmakers providing an interconnected episode to the notable omnibus feature Four Rooms. Her contribution – “The Missing Ingredient” – would be the only vignette of the film to directly involve a dreamlike fantasy element in her portraying of a witch coven using a magical spell to resurrect an erstwhile goddess.

It’s important to note too that Anders was a member of what some critics/filmmakers have referred to in the past as the Sundance Film Festival “Class of ‘91/92” – alongside fellow Four Rooms auteurs Robert Rodriguez and Quentin Tarantino, as well as Gregg Araki, Katt Shea Ruben, Richard Linklater, Todd Haynes and others who broke out at the turn of the early nineties in the growing so-called “indie film” scene, as best described in James Mottram’s book The Sundance Kids: How the Mavericks Took Back Hollywood.

Anders was one of many young, brash, irreverent filmmakers who were happy to mix into their artistic vision some timely, marketable trendiness (worth noting here the soundtrack of Gas, Food Lodging is by one of the monsters of the era’s “grunge” scene – Dinosaur Jr. frontman J. Mascis) and box office bait cast members in an understandable vie to crossover into mainstream appeal.

Consider how creator, star and executive producer Roseanne has in the past defended her controversial final season of the original run of her eponymous show as being “truthful” in showing that her character of “Roseanne’s” winning the lottery dramatically changed the course of her and her family’s sub-modest lifestyle.

To the actual Roseanne, this seemingly outlandish choice was merely a reflection of the actual reality of her own life, of which the entire series had unrepentantly been a reflection. The real Roseanne really did “win the lottery” in her real life, and so she felt no regret in having her character “Roseanne” have a similar outcome (until, SPOILER ALERT: we learn the really real truth in the last few minutes of the initial series’ run).

In a similar meta-way, Anders was being radically “truthful” in Gas, Food Lodging. She presented a world and characters awash in fantasy aspiration … in order to broadcast a sense of actively “chasing the dream” for herself, her family and – with the support of colleague filmmakers at this unique time period in American cinema where a Tarantino or Rodriguez or Linklater could go from dreaming it and watching it to making it without having to completely go the route of big budget sequels or without completely relinquishing their creative control and effulgent independent spirit – the entire independent film community.

It was, after all, a community that was shifting more toward the conventions, aesthetic qualities and cast choices of commercial Hollywood in a manner that proved to open doors for unique, previously stifled voices around the country, while continuing to shine light on elements of society that had otherwise gone unheralded for far too long.

What a jump Tarantino made from the innovative, resourceful, comparably “small-time” Reservoir Dogs to the wildly ambitious and star-studded Pulp Fiction only two years later. Think of Linklater moving from his incredibly DIY first feature of It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books, to follow-up career-starter Slacker and then immediately skyrocketing into his crowd-pleasing paean to nostalgia Dazed and Confused.

Or consider Gus Van Sant’s rise from the nearly unwatchable (physically; you can barely see or hear it) Mala Noche of 1986 to his own career-making Drugstore Cowboy and, of course, My Own Private Idaho, both released less than five years later.

Little more need be said about the prime example of such a shift: the explosively prolific career of Steven Soderbergh, who went from the ultra-modest Sex, Lies, and Videotape, to becoming one of the most eclectic, acclaimed and commercially successful auteurs in American cinematic history.

It was around this time too that filmmakers such as John Singleton and Spike Lee broke out with similar mixes of genuine experiences and mainstream accessibility in the telling of films dealing with the big city urban climate of the period in such early critical and commercial hits as 1991’s Boyz N the Hood and 1989’s Do the Right Thing.

Gleeful schlockmeisters Troma would proudly pick up the torch left still slightly burning from the likes of predecessors Roger Corman, Russ Meyer and John Waters to present a new form of sub-indie “midnight movie” productions in the likes of The Toxic Avenger series and a slew of other films such as Tromeo & Juliet, many of which would at once keep the fires of the no-budget creativity of punk going strong … while nurturing the rise of wildly successful mainstream filmmakers who would grow up to become Trey Parker/Matt Stone, Eli Roth and The Guardians of the Galaxy’s James Gunn.

Gas, Food Lodging’s seemingly incompatible mixture of luminous fantasies and rougher realities, its meta-sense of truthful “indie” spirit and commercial viability can be seen across the globe in such European productions of the time as Mike Leigh’s Life is Sweet and Naked, Jean-Jacques Beineix’s Betty Blue, and an entire decade of like-minded eighties/early nineties films from Catherine Breillat, Agnès Varda, Maurice Pialat, Bertrand Blier, Michael Haneke, Claire Denis, Alan Clarke and Pedro Almodóvar.

This was the time of the so-called Hong Kong Second Wave, represented by such filmmakers as Wong Kar-wai. Mexican actor and filmmaker Alfonso Arau released his own submission to this scene that easily blurred indie/genuine filmmaking with unashamedly commercial aspirations: the period piece Like Water for Chocolate (released in – surprise, surprise – 1992).

Australian PJ Hogan would beat both Mama Mia! and My Big Fat Greek Wedding to the punch in more ways than one with his charmingly resourceful but marketable 1994 production of Muriel’s Wedding before, as with Anders and fellow indies, taking off shortly into the realm of Julia Roberts rom-coms and a big-budget Peter Pan adaptation, the ultimate in fantasy aspiration.

It was a time period that obliterated the concept of “selling out,” disrupting the limit of how palatable-to-the-mainstream filmmakers were willing to craft their singular films in order to bring to the fore otherwise unilluminated areas of the American experience.

We saw this for a few years leading up to this point even in the upper crust realm of New York City literati, as revealed in the works (and lives) of the so-called “Brat Pack”: young authors like Bret Easton Ellis, Jay McInerney and Tama Janowitz.

We saw it throughout the eighties in the movements toward hip-hop, hardcore punk, riot grrrl and indie/college rock, as wonderfully tracked in Michael Azerrad’s essential book Our Band Could Be Your Life, Tricia Rose’s Black Noise, Sara Marcus’ exhaustive Girls to the Front and the frolicking jaunt that is Marc Spitz’s more recent Twee, as well as the meticulously chronicled rock docs Fugazi: Instrument and Sundance golden child Dig!.

Heck, it’s worth pointing out that even the realm of children’s television was affected by this tension between independent artistic spirit/authenticity and commercial viability anent what we saw in the astounding outpouring of original programming coming out of the unlikeliest of places – Nickelodeon – as chronicled and described in full in my own book SLIMED! An Oral History of Nickelodeon’s Golden Age.

As the filmmakers, authors, musicians and other artists in this period continued struggling to (and, as was often the case with those aforementioned, succeed at) find the right combination of mainstream accessibility and artistic integrity over the years to come, we’d see indie empires (read: Artisan, Shooting Gallery, Fine Line, the stream of arthouse divisions of large studios such as Paramount) come and just as often go.

There was to come a new, conscious and unmistakable shift back to those kinds of rougher, grittier and “screw-you-if-you-can’t-take-it” films of the late sixties and seventies – most visibly in the rather tongue-and-cheek named “Mumblecore” scene of the early 2000s – as we’ll see coming up as we make our way into the final half of our series, starting with Jeff Nichols’ 2007 debut feature, Shotgun Stories.

MATHEW KLICKSTEIN is (for the time being) a Boulder-based writer/filmmaker who recently completed and has been touring his documentary on 80s/90s TV icon Marc Summers, On Your Marc, to be widely-released soon. His next book, Springfield Confidential: Jokes, Secrets, and Outright Lies from a Lifetime Writing for TheSimpsons (co-written with lifetime series writer/producer Mike Reiss, foreword by Judd Apatow), will be released through Harper Collins this June. You can keep up with his regular shenanigans at www.MathewKlickstein.com.