WALK INTO THE SEA: DANNY WILLIAMS AND THE WARHOL FACTORY, A

The first time I encountered Andy Warhol was probably typical for Americans of my generation; I saw him in one of his numerous TV cameo appearances, probably on something like the ABC comedy The Love Boat. The fact that this moment, or something like it, represents my initiation into the world of Warhol would probably tickle the artist himself. A visionary painter, illustrator, graphic designer, photographer and filmmaker, Warhol’s pop art legacy was well cemented by the time he found himself mugging his way through network television programs. Take a look…

The first time I encountered Andy Warhol was probably typical for Americans of my generation; I saw him in one of his numerous TV cameo appearances, probably on something like the ABC comedy The Love Boat. The fact that this moment, or something like it, represents my initiation into the world of Warhol would probably tickle the artist himself. A visionary painter, illustrator, graphic designer, photographer and filmmaker, Warhol’s pop art legacy was well cemented by the time he found himself mugging his way through network television programs. Take a look…

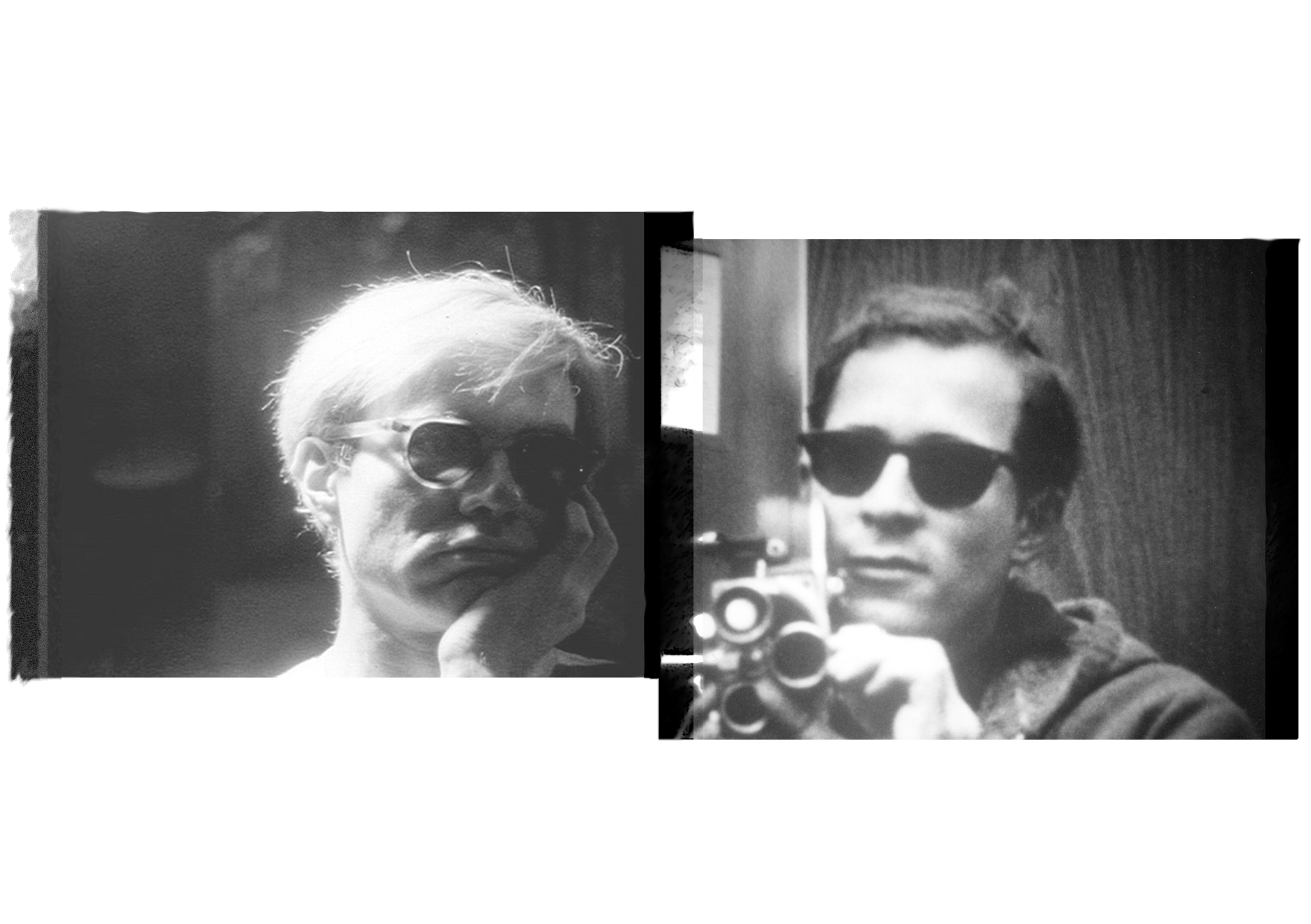

Warhol always seemed to me the epitome of the benign artist; painfully shy, seemingly humble and oh-so hard working, his public persona went down easily. But it was his appropriation of iconic images that I found so thrilling as a young man, the idea that these icons became, well, more iconic in the act of being re-interpreted. Indeed, which image is more recognizable, more valuable today, a photograph of Marilyn Monroe or Warhol’s multi-colored industrial repetitions of her smiling face? There can be no doubting Warhol’s influence and powers as an artist, only a discussion of the quality of his legacy.

In recent years, the re-examination of Warhol’s legacy has focused squarely on the man himself as questions have been raised about the way in which Warhol’s penchant for appropriation in his art may simply have been an extension of the intrigues that raged through his personal life. It wasn’t until the Lou Reed/John Cale album Songs For Drella that I first heard Warhol’s nickname (a combination of Dracula and Cinderella, attributed to Factory member Ondine), but as more and more stories have emerged in recent years about the way in which Warhol presided over his Factory, the nickname’s reference to Bram Stoker’s vampire has come to represent the dark side of Warhol’s personality for me, that ice-cold, indifferent part of him that could walk away in boredom from friends and acquaintances that no longer struck his fancy in just the right way.

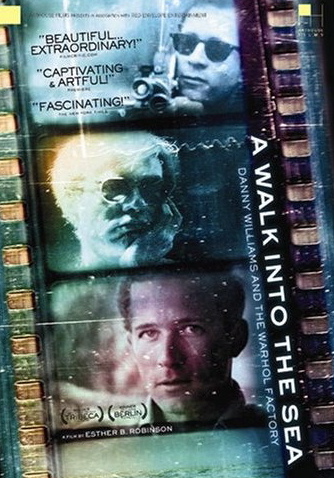

In her film A Walk Into The Sea: Danny Williams And The Warhol Factory, Esther B. Robinson examines the ramifications of Warhol’s dark side through the prism of her own uncle’s extraordinary life. Danny Williams was an up-and-coming editor and filmmaker in the early 1960’s New York City film scene when he fell in with the Factory crowd. In the middle 1960’s, he became Warhol’s lover, a relationship which came with privileges (access to the scene and the equipment required to make his short film Factory) and its own problems; the feuds, rivalries, petty jealousies, sexual liaisons and personal humiliations on display at The Factory would have been enough to make Richard III blush. Some, like the filmmaker Paul Morrissey (depicted here as one of Williams’ primary rivals, constantly downplaying the filmmaker’s role in Factory life) were able to navigate their way through the Factory years with Machiavellian skill, while others, like Williams himself, seem to have been drawn to Warhol’s bright, creative flame only to find themselves too fragile to withstand the emotional rigors of life at the tantalizing edge of fame.

In Williams’ case, those dreams of acceptance, or at least our public understanding of those dreams, came to an end when, on a visit to his family’s coastal New England home, the young filmmaker borrowed a family car, drove it to the ocean and disappeared forever. With no record of his death and no suicidal motive articulated by Williams himself, Danny’s absence and loss has a spectral quality in the film that is matched by the fleeting, timeless images he captured in his own work. Robinson honors Williams’ creative record by showing Factory in its entirety during the film, but it is her search for an answer, and her film’s humble recognition that one will probably never be found, that drives the film’s narrative. Cutting between Factory alumni and her own family (represented most movingly by Robinson’s grandmother), Robinson paints the picture of a community that had embraced Williams in one moment and, through the political machinations inherent in Factory life, discarded him the next. In Robinson’s telling, the blame rests squarely on the shoulders of Warhol himself, not so much for his action or inaction in regards to Williams’ needs, but for creating and leading a community whose sole allegiance was to his aesthetic and personal whims. It was the heartbreak of rejection that drove Williams’ to the sea that night, Robinson seems to argue, his feelings muted by the glare of the Factory spotlight.

In Williams’ case, those dreams of acceptance, or at least our public understanding of those dreams, came to an end when, on a visit to his family’s coastal New England home, the young filmmaker borrowed a family car, drove it to the ocean and disappeared forever. With no record of his death and no suicidal motive articulated by Williams himself, Danny’s absence and loss has a spectral quality in the film that is matched by the fleeting, timeless images he captured in his own work. Robinson honors Williams’ creative record by showing Factory in its entirety during the film, but it is her search for an answer, and her film’s humble recognition that one will probably never be found, that drives the film’s narrative. Cutting between Factory alumni and her own family (represented most movingly by Robinson’s grandmother), Robinson paints the picture of a community that had embraced Williams in one moment and, through the political machinations inherent in Factory life, discarded him the next. In Robinson’s telling, the blame rests squarely on the shoulders of Warhol himself, not so much for his action or inaction in regards to Williams’ needs, but for creating and leading a community whose sole allegiance was to his aesthetic and personal whims. It was the heartbreak of rejection that drove Williams’ to the sea that night, Robinson seems to argue, his feelings muted by the glare of the Factory spotlight.

All of which begs the question of what Andy Warhol owed to the people with whom he chose to associate. As the leader of a troupe of lost, impossibly beautiful young people from all walks of life, Warhol is often painted as a sort of imperial prelate, blessing and cursing the lives of others with a smile or frown. And yet, as Robinson’s film makes clear, there is an individual responsibility in not granting this power to others, in living your life on your own terms, that seemed to be missing from so many of Warhol’s friends and associates. Robinson’s grandmother clearly articulates her own wish of reclaiming Williams from Warhol’s noir-ish shadow, but the director is also smart enough to know that her uncle’s dreams, desires and works were a part of a powerful, eternal and creative moment that give value to telling his story. The great irony of A Walk Into The Sea is that the story is a tragedy for precisely the same reasons as it is worth telling. Because she recognizes and acknowledges this conflict, Robinson is able to hit an abundance of perfectly balanced notes, none more powerful than the film’s exceptional, Velvet Underground-influenced score by her husband T. Griffin. Despite her personal proximity to the film’s subject matter, Robinson is an even-keeled director who listens to the story she’s told and who utilizes an aesthetic strategy that gives context and meaning to both Williams’ films and her own exploration of his legacy. The result? She’s made a small marvel of a movie, a story that longs for answers and instead finds terrible beauty in the unknowable.

— Tom Hall

(Buy A Walk Into The Sea at Amazon.)