(Unfortunately, DVD distribution of A Moment of Innocence has been discontinued, as a result of New Yorker Films’s recent closing. But copies of it can still be found for sale online.)

For admirers of the great Iranian filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf, the news that he has been operating from his temporary base in Paris as the official foreign spokesman of Mir Hussein Mousavi’s presidential campaign—urging Western governments as well as Iranian expatriates not to recognize Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s claim to victory—was a surprising and inspiring development, even during a momentous couple of weeks that have brought no shortage of surprising, inspiring developments. Although Makhmalbaf’s reputation in the U.S. and Europe has been somewhat overshadowed by that of his near-contemporary Abbas Kiarostami, a handful of his films, including The Peddler (1987), Salaam Cinema (1994), and Gabbeh (1995), were crucial in raising international audiences’ awareness of modern Iranian cinema. My own favorite of Makhmalbaf’s works is 1996’s A Moment of Innocence. The film may seem especially relevant right now, since its explicit subject is the disillusionment and diminishment of populist hopes during the years following the 1979 revolution, and its implicit message is that the young of Iran must lead their society in a new direction. But its power and profundity transcend the merely topical.

A Moment of Innocence plays off the known facts of Makhmalbaf’s biography—and the man’s life makes for a story that’s as astounding as any of his movies. In 1974, the seventeen-year-old Makhmalbaf was a true believer in the radical Islamic cause, determined to help bring down the Shah. He planned to stab a policeman in order to steal his gun. Once armed, he would then rob a bank, and donate the money to the revolutionary struggle. The plan went awry: the policeman was wounded, but Makhmalbaf was captured and sent to prison, not to be released until the Shah’s government was toppled in ‘79.

As a religious-fundamentalist teenager, Makhmalbaf thought movies were a corrupting influence and told his mother she would go to hell for watching them. Now, though, he found himself drawn to cinema. His first films were by his own account moralistic and didactic expressions of Islamic teachings, but as he aged, and observed what was happening in his country, he began to have doubts about his faith as well as about the revolution to which he had sacrificed his youth. He became more of a social critic, speaking out against the exploitation of the poor and the oppression of women. During the first phase of his career, he told the critic Hamid Dabashi, he portrayed “leftists as evil and religious people as good.” In the films of his second phase, “the poor are all good and the rich are evil. That is to say, these films lack psychological depth. In the first period, truth is defined by religion, and in the second, it is defined by, let’s say, social justice. In the end, they’re one-sided. Absolutist.” But in his later, more complex and multi-faceted films, “everyone is simultaneously good and bad, everyone is gray” and “there is no center of truth.”

As a religious-fundamentalist teenager, Makhmalbaf thought movies were a corrupting influence and told his mother she would go to hell for watching them. Now, though, he found himself drawn to cinema. His first films were by his own account moralistic and didactic expressions of Islamic teachings, but as he aged, and observed what was happening in his country, he began to have doubts about his faith as well as about the revolution to which he had sacrificed his youth. He became more of a social critic, speaking out against the exploitation of the poor and the oppression of women. During the first phase of his career, he told the critic Hamid Dabashi, he portrayed “leftists as evil and religious people as good.” In the films of his second phase, “the poor are all good and the rich are evil. That is to say, these films lack psychological depth. In the first period, truth is defined by religion, and in the second, it is defined by, let’s say, social justice. In the end, they’re one-sided. Absolutist.” But in his later, more complex and multi-faceted films, “everyone is simultaneously good and bad, everyone is gray” and “there is no center of truth.”

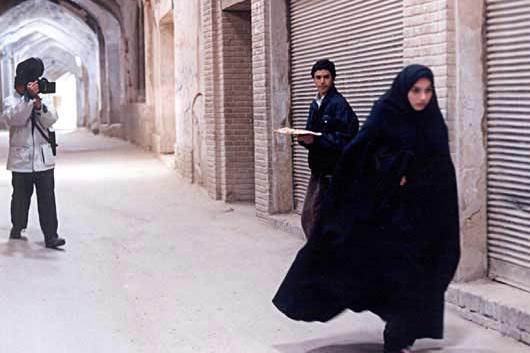

There’s certainly no “center of truth” in A Moment of Innocence, a fiction masquerading as a documentary. The film begins with a middle-aged man, a retired policeman and now an aspiring actor, approaching Makhmalbaf’s home. We learn that he’s the policeman Makhmalbaf stabbed years earlier. Makhmalbaf hires him to act in his new movie. The ex-policeman is paired with a young man who will play his 1974 self. Likewise, Makhmalbaf casts another youth to play himself as a teen. The two older men “direct” the younger ones on screen, training them in their respective roles as officer and militant, so that Makhmalbaf can re-enact the fateful assault. Why?

“To recapture my youth with the camera,” Makhmalbaf tells us. But the camera lies. And Makhmalbaf wants us to know that it lies, and to implicate himself in the act of lying. The attentive viewer realizes early on that the documentary feel of the film is a façade. As the story progresses, this becomes more and more obvious; eventually, Makhmalbaf blatantly foregrounds the fact that he’s playing with us—toying with time schemes, breaking the frame, manipulating people and events from off-screen. The director is doing to his film what he and his former adversary are doing within the film: rearranging the present in an attempt to relive the past. But the older men do this within the film by imposing their own beliefs, their own regrets and resentments, onto their young charges. And the Makhmalbaf who directs the film understands what the Makhmalbaf who acts in the film does not: that this is a crime against youth. These two representatives of the pre-revolutionary generation—the former servant of authority, and the former anti-authoritarian radical—are clouded by egotism and selfishness and wounded pride, and are unable to teach their juniors how to learn from the mistakes they themselves made. The re-enactment threatens to become an act of repetition-compulsion in which idealism once again leads to bloodshed, and hope curdles into hatred. It’s up to the post-revolutionary generation to rewrite the script they’ve been handed. And so they do, in the film’s stunning final shot—an image that recalls the Biblical directive to beat swords into plowshares, magically transforming the weapons of war into offerings of peace.

“To recapture my youth with the camera,” Makhmalbaf tells us. But the camera lies. And Makhmalbaf wants us to know that it lies, and to implicate himself in the act of lying. The attentive viewer realizes early on that the documentary feel of the film is a façade. As the story progresses, this becomes more and more obvious; eventually, Makhmalbaf blatantly foregrounds the fact that he’s playing with us—toying with time schemes, breaking the frame, manipulating people and events from off-screen. The director is doing to his film what he and his former adversary are doing within the film: rearranging the present in an attempt to relive the past. But the older men do this within the film by imposing their own beliefs, their own regrets and resentments, onto their young charges. And the Makhmalbaf who directs the film understands what the Makhmalbaf who acts in the film does not: that this is a crime against youth. These two representatives of the pre-revolutionary generation—the former servant of authority, and the former anti-authoritarian radical—are clouded by egotism and selfishness and wounded pride, and are unable to teach their juniors how to learn from the mistakes they themselves made. The re-enactment threatens to become an act of repetition-compulsion in which idealism once again leads to bloodshed, and hope curdles into hatred. It’s up to the post-revolutionary generation to rewrite the script they’ve been handed. And so they do, in the film’s stunning final shot—an image that recalls the Biblical directive to beat swords into plowshares, magically transforming the weapons of war into offerings of peace.

When the films of Kiarostami and Makhmalbaf and others began to win attention and awards at film festivals and art houses around the world, part of their appeal, no doubt, was the window they provided onto a foreign culture that many viewers were curious about—because we had friends with family roots there, and/or because we knew that the news media were only giving us a filtered and fractional view of the country. But mere reportage couldn’t explain the films’ collective impact. In a time when nostalgists and know-nothings were insisting that the great achievements of film were all in the past, here was a national cinema (or at least its independent/art-film division) whose leading exponents were revitalizing the art form—reaching back to the roots of documentary and neorealism to bring us snapshots of social reality, while also pushing the boundaries of formal experimentation. That all this was being accomplished under a repressive political regime and the harshest of censorship codes (and on very low budgets) seemed a miracle.

But now, the new wave of post-’79 filmmaking has crested and broken. What happens next to Iranian cinema depends largely on what happens to Iranian society as a whole. Will the constraints and clampdowns of Ahmadinejad’s first term continue and worsen? Or will the spirit of open revolt that has been loosed in the past few weeks make itself felt in the arts, either through a gradual liberalization of the mainstream, or a burgeoning underground movement? Whichever way things go, it seems clear that the Iranian cinema that has meant so much to so many of us is about to enter a period of eclipse. The younger filmmakers beginning to emerge are facing conditions so different from those their predecessors labored under that the older generation’s work now seems to belong definitively to a past era. But in time, the best of their films—with A Moment of Innocence near the very top of the list—will re-emerge to stand apart from and above their immediate historical moment, as major cinematic contributions to our halting, fumbling attempts at self-understanding.

But now, the new wave of post-’79 filmmaking has crested and broken. What happens next to Iranian cinema depends largely on what happens to Iranian society as a whole. Will the constraints and clampdowns of Ahmadinejad’s first term continue and worsen? Or will the spirit of open revolt that has been loosed in the past few weeks make itself felt in the arts, either through a gradual liberalization of the mainstream, or a burgeoning underground movement? Whichever way things go, it seems clear that the Iranian cinema that has meant so much to so many of us is about to enter a period of eclipse. The younger filmmakers beginning to emerge are facing conditions so different from those their predecessors labored under that the older generation’s work now seems to belong definitively to a past era. But in time, the best of their films—with A Moment of Innocence near the very top of the list—will re-emerge to stand apart from and above their immediate historical moment, as major cinematic contributions to our halting, fumbling attempts at self-understanding.

— Nelson Kim

Pingback: Hammer to Nail » Blog Archive » CLOSE-UP – Kiarostami’s Doctored Documentary Turns 20

Pingback: THIS IS NOT A FILM – Hammer to Nail