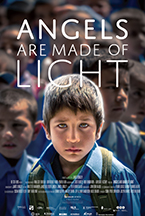

ANGELS ARE MADE OF LIGHT

(Filmed throughout three years, James Longley’s documentary Angels Are Made of Light follows students and teachers at a school in an old neighborhood of Kabul that is slowly rebuilding from past conflicts.)

An elliptical documentary meditation on the ravages of foreign occupation and civil war, James Longley’s Angels Are Made of Light follows various residents – mostly children – of Kabul, Afghanistan, as they navigate the difficulties of a post-Taliban/post-American-invasion world. Longley has traveled similar territory before, with the 2006 Iraq in Fragments, and his rapport with his subjects feels genuine and comfortable. They allow him direct access into their lives, helping make of this movie an intimate portrait of a nation in ongoing crisis. Along the way, Longley provides a good deal of Afghanistan’s 20th-century history, allowing us to understand the role that the United States and others have played in the past to undermine the present. The future is not yet written, and the brave young souls at the heart of the film offer promise that it may be less bleak. Maybe.

There are no talking-head interviews, but Angels Are Made of Light is filled with the voices of its main characters, as Longley underlays their narration in the sections that belong to them. Among the compelling ensemble, we meet Sohrab and his brother Rostam, who represent different paths within one family, the former seeking escape through study, the latter through mechanical labor. A third, younger brother, Yaldash, yearns to study, as well, but is compelled by his father to work as an apprentice tinsmith. And then there’s Nabiullah, another studious boy whose friend was killed by a suicide bomber. He aches for an Afghanistan with neither Taliban nor Americans. We also meet young girls learning to read, taught by women like Hasiba, whose voice we also hear; she firmly believes that female literacy holds the key to a better tomorrow.

Indeed, the teachers here are heroic in their efforts, holding classes in bombed-out buildings, as well as tents, with little to no supplies. We open with the image of dust swirling in a beam of light through a hole in the roof of one such location, immediately evoking the movie’s title; the line actually comes from the students’ religion lessons, taught as a core belief of Islam. One of their teachers, Moqades, uses his platform to rail against factionalism and for non-violent solutions. His ideas take hold, at least among the pupils we see. Mature beyond their years, the youth of Afghanistan internalize all that is wrong now to avoid repeating the same mistakes.

But the weight of the past bears down heavily. As Longley shows, the region has for so long been a victim of outside interference and subsequent internal mismanagement. In the 1970s alone, Afghanistan shifted quickly, though coups and revolutions, from the rule of Zahir Shah to Daud Khan to Nur Mohammad Taraki to Hafizullah Amin to, finally, the USSR-installed Babrak Karmal. Zahir Shah, though a king who ruled for 40 years, from 1933-1973, nevertheless oversaw a period of growth and stability. Since his overthrow, life for ordinary Afghans has been anything but peaceful.

Not surprisingly, our protagonists shrug their shoulders during the course of the 2014 presidential elections, in which the two-term Hamid Karzai cedes power to the present-day leader, Ashraf Ghani. What difference will such changes make in the lives of ordinary citizens? After all, they struggle to survive in a country that has received billions in foreign aid that almost all vanished into the pockets of people like Karzai. Angels are made of light, and politicians of money; same old, same old. Perhaps this time, with the rising generation of angels, things could be different. We’ll know eventually. For now, we have this beautiful movie to give us hope.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)