(3 Women premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 1977, where Shelley Duvall won the award for Best Actress. Criterion recently re-released it on DVD and Blu-ray.)

3 Women is set in a hazy, washed-out desert town that looks to be somewhere between Los Angeles and Palm Springs. Though familiar in certain regards, the nameless town is ultimately alien even to this lifelong Californian, a foreignness most readily explained by the ways in which it enhances (and is enhanced by) the dreamlike surreality of a deeply unsettling film. Robert Altman, in perhaps his most abstract directorial effort, spends the first several minutes of screentime establishing his chosen mood and tone—here an initial placidity that slowly gives way to mounds of unease teeming beneath—with little dialogue of any seeming consequence before properly introducing us to Pinky and Millie, his dual protagonists. Throughout the rest of the film the two women’s personalities bounce off, absorb, and ultimately merge with one another in a way that blurs individual identity and renders them virtually indistinguishable from one another. Post-Persona, pre-Mulholland Drive, the film is like a map without a clear legend: compellingly inscrutable.

The interplay between Millie and Pinky quickly establishes itself as 3 Women‘s narrative and thematic centerpiece. Opposites attract, clearly, but here they also engage in a dark symbiosis from which much of the film’s hinted-at meaning derives. As Millie, Shelley Duvall is superb; petty and quietly calculating but also oblivious to others’ largely negative perceptions of her, she spends much of her energy putting on the airs of a sophisticated and sought-after woman of society—a facade that instantly draws the attention of Sissy Spacek’s doe-eyed Pinky. At first, Pinky looks up to her new coworker and roommate the way any new girl desperate for a friend always seems wont to; she’s either unaware of or indifferent to the fact that no one else seems to like Millie. Pinky’s puerile enthusiasm comes out early and often: upon arriving at a gimmicky bar with a ghost town motif, she exclaims “What is this, Disneyland?” (Once inside, she pours salt into her mug of beer before drinking it.) She’s instantly taken with Millie, and makes no attempt to hide it: “You’re the most perfect person I ever met,” she tells her. Clearly, the only logical next step is for her to take on key aspects of her friend’s personality.

Millie’s pervading concern with appearances is her most telling trait. She treats nearly every conversation, no matter how unrelated, as an opportunity to allude to her many romantic entanglements (all of which are exaggerated) or some other element of her highly cosmopolitan lifestyle. An example: “I’m making us some tuna melts for dinner. They’re real easy and they only take about fifteen minutes to make. I’ll tell you how so you can make ’em yourself if I’m out on a date or something.” She then proceeds to give an exhaustive, step-by-step account of her recipe in a manner both humorous for its absurdity and frightening for its earnestness. Duvall’s performance, though not overtly physical, is nevertheless enhanced by her delicately lanky physique—we see her fragility even as she does her best to project strength and independence. She’s transparent but oblique at the same time, and all but impossible to turn away from once she’s caught your gaze. Pinky is less attention-grabbing, at least at first, and so her plotting has the effect of sneaking up on Millie (and us) rather than announcing itself outright.

Millie’s pervading concern with appearances is her most telling trait. She treats nearly every conversation, no matter how unrelated, as an opportunity to allude to her many romantic entanglements (all of which are exaggerated) or some other element of her highly cosmopolitan lifestyle. An example: “I’m making us some tuna melts for dinner. They’re real easy and they only take about fifteen minutes to make. I’ll tell you how so you can make ’em yourself if I’m out on a date or something.” She then proceeds to give an exhaustive, step-by-step account of her recipe in a manner both humorous for its absurdity and frightening for its earnestness. Duvall’s performance, though not overtly physical, is nevertheless enhanced by her delicately lanky physique—we see her fragility even as she does her best to project strength and independence. She’s transparent but oblique at the same time, and all but impossible to turn away from once she’s caught your gaze. Pinky is less attention-grabbing, at least at first, and so her plotting has the effect of sneaking up on Millie (and us) rather than announcing itself outright.

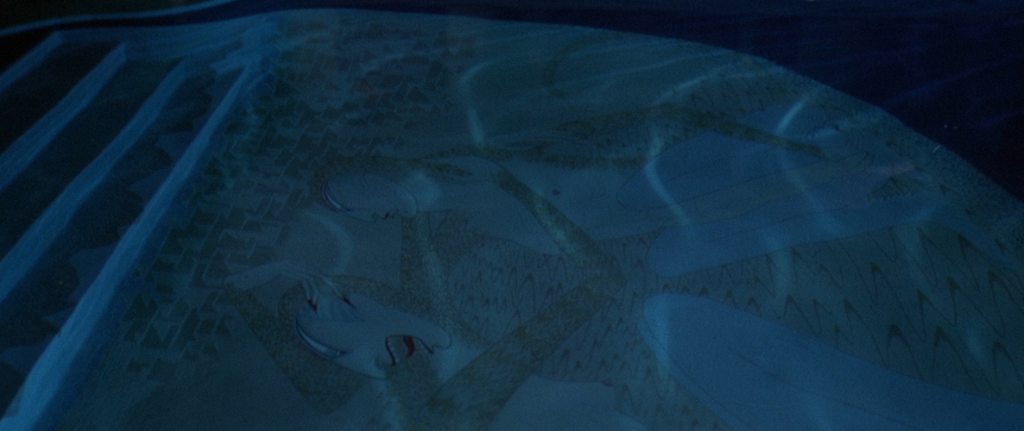

The third woman, Willie, is by far the least frequent presence onscreen, but she’s responsible for the film’s most vital setpiece: a series of murals painted on the inside of swimming pools. These paintings are not unlike the monolith in 2001 in that they could serve as the means by which we come to understand the film’s rich inner life if only they were themselves comprehensible. Sexualized grotesques with their heads turned to the side like hieroglyphs, they’re a sort of visual (if not quite physical) embodiment of the unease evoked by nearly all of the film’s 122 minutes. If everyone’s—or anyone’s, for that matter—outer appearance more accurately resembled their inner state, it might look something like this.

The film is so psychologically dense and freewheeling that its continuously unnerving effect almost classifies it as horror. Altman achieves all this with nary a hint toward actual violence or even fear among the characters themselves for the first hour; the dangerously soft-spoken tension between Millie and Pinky (whose actual names, it’s revealed after a short while, are both Mildred) proves more than enough to make the experience a haunting one. A near-suicide attempt by way of a nosedive into a swimming pool halfway through the film jolts these dormant undertones into consciousness: from that point on, the story plays host to (possibly feigned) amnesia, role reversals, and a steady descent into delirium from which it never emerges. Navigating this impressionistic underbelly requires one to haphazardly extract bits of meaning here and there, knowing all the while that any picture formed is unlikely to be make complete sense. Altman has aptly described 3 Women as being akin to a watercolor, a metaphor that goes a surprisingly long way toward understanding it—or, failing that, accepting that certain of its elements defy explanation regardless.

Given that the pool in question is marked by Willie’s enigmatic murals, it would follow from Altman’s dream logic that they’re part of what changes Pinky. She wakes up from her coma aggressive, cruel, and literally unaware of who she is both on her own and in relation to Millie. It isn’t until an extended dream sequence centered around water, death, and the murals—which by now have taken on the air of cave paintings from another world—that she returns, in part, to her former self. But it’s too late. Damage and change are cumulative here and, unlike dreams, apparently irreversible.

Audio/Visual: Several of the film’s key scenes are seen through the opaque lenses of mirrors, water, and other surfaces as disorienting as they are reflective. Watching it on this disc, the effect is more mesmerizing than ever. 3 Women‘s cool blue hues (seen most prominently in the drained-pool murals) are as airy as they are pristine, and the grain, when noticeable at all, is so in a good way. Much of the drama comes as much from wordless interactions as from dialogue, and it’s here that the haunting, flute-driven score is foregrounded. All sounds appropriately creepy here, with a sharpness that helps cut through the thematic blurriness.

Audio/Visual: Several of the film’s key scenes are seen through the opaque lenses of mirrors, water, and other surfaces as disorienting as they are reflective. Watching it on this disc, the effect is more mesmerizing than ever. 3 Women‘s cool blue hues (seen most prominently in the drained-pool murals) are as airy as they are pristine, and the grain, when noticeable at all, is so in a good way. Much of the drama comes as much from wordless interactions as from dialogue, and it’s here that the haunting, flute-driven score is foregrounded. All sounds appropriately creepy here, with a sharpness that helps cut through the thematic blurriness.

Supplements: In a commentary track recorded in 2003, Robert Altman discusses how the film’s title, main cast, and setting came to him in a dream while his wife was in the hospital. In a fittingly recursive detail, Altman further dreamt that he would wake up, take notes on his dream, fall back asleep, and repeat. But these were actually all dreams within dreams, and in fact the filmmaker didn’t even keep a notepad by his bed. His insights are fascinating to listen to, especially because 3 Women is such a nebulous film. Unfortunately, there’s little else of note here—the gallery of rare stills is a welcome addition, but the theatrical trailer and TV spot are nothing to write home about. Still, it says a lot about how much Criterion spoils cinephiles that, for them, this supplemental material is on the light side.

— Michael Nordine