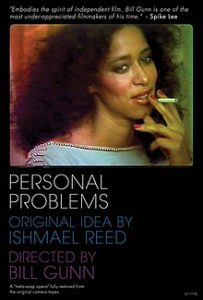

PERSONAL PROBLEMS (SPLIT SCREEN VERSION)

(Friday, August 27, Metrograph began presenting Personal Problems: Split-Screen Version, a new restoration deconstructing Bill Gunn’s groundbreaking 1980 film. You can watch it here now. Like what you see here on Hammer to Nail? Why not give just $1.00 per month via Patreon to help keep us going?)

If you could fantastically fabricate another film or novel by anyone gone-too-soon, whom would you choose? On an inevitable and enviable short-list should appear the multi-talented Bill Gunn. Arguably best-known as an actor and playwright, his second feature — his first was shelved by Warner Bros. and never officially released — was the legendary Ganga & Hess. A decade later, he starred in Kathleen Collins’ wonderful Losing Ground (again with Duane Jones, portrayer of the aforementioned Hess and the exceptional lead protagonist of Night of the Living Dead).

In-between these two milestones, after an earlier career on episodic television and an adaptation of the novel The Landlord into the film-of-the-same-name by Hal Ashby, Gunn collaborated with Ismael Reed on the premise for Personal Problems, a “meta soap-opera” following nurse Johnnie Mae Brown, her husband Charles Brown and her father-in-law and how all three occasionally intersect with jazz pianist Raymon (and other friends and family) in and around Harlem. Kino Lorber — specifically Bret Wood — handled the original video footage re-digitized by Jake Perlin for the 2018 reissue. Wood again gives the material the meta-meta treatment in a deconstructed split-screen version premiering at the Metrograph in New York and online thereafter.

Made-for-television (although rarely presented in that format) in the wake of the Roots mini-series, arguably U.S. viewers were ready for other representations of the Black experience in America. If so, no one in a position to fully finance the project deemed it necessary. From the initial version of an episodic radio drama , Personal Problems evolved into a half-hour “pilot” and then two episodes — generally packaged and screened together in subsequent years — and now this side-by-side synced split-screen theme-and-variations. What it gains from these various permutations can be accurately assessed by way of its assorted parts. It is a work that continues to be enhanced by each presentation.

Vertamae Grosvenor, former Sun Ra Arkestra vocalist, NPR host, “culinary griot” and author, and Sam Waymon, Nina Simone’s brother and Gunn’s former roommate, lead a menagerie of other talented folks through a dense maze of human intricacies and interactions. The actors take the framework of each scene from Reed’s scenario and riff, sometimes literally — in a handful of jazz performance sequences — and other times figuratively, as the dialogue meanders between the characters (particular in scenes where many of the ensemble are present).

Production-wise, Personal Problems was apt for experimentation, blending elements of documentary and fiction, scripted scenes with improvisation. Cinematographer Robert Polidori, a former Anthology Film Archives assistant who’d earlier studied with Paul Sharits (and, presently, best known as a large-format still photographer), opted to shoot the project with two cameras simultaneously on ¾” U-Matic tape. This deconstruction pairs those two images from two perspectives, retaining the “action” and “cut” cues to reveal a great deal about Gunn’s process of setting situations in motion and then largely staying out of the fray. His generous reputation as a director who created immensely supportive spaces for his actors to perform is entirely on display here.

The results, unsurprisingly, are relentlessly uncommercial. Visually and audibly murky at times, Gunn and Reed seem to be defying anyone easy entry into the material. It is all rather rough and narratively loose by design. It is not there to welcome you in. The viewer needs to be present and observant to accurately gather the goings-on. Appreciate it on its own terms and you’ll be rewarded.

Much has been mentioned elsewhere of the shooting style of the production although multi-camera shoots have been a key aspect of television production back to Karl Freund’s work (in the 1950s) and earlier. However, the lengthy uninterrupted takes lend themselves rather well to a side-by-side presentation. What the parallel framing reveals about the filmmaking process is rather remarkable. Certain aspects of the results resemble Rob Nilsson’s similarly shot-on-video Signal 7, released four years after, and one could imagine Gunn continuing in an identical direction if he hadn’t passed away prematurely a mere handful of years later.

What this all could mean to anyone with no familiarity of Gunn’s work nor the works of other Black artists from the 1980s or earlier — or even later — is uncertain. Can an appreciation for the split-screen deconstruction exist without seeing the slightly-longer single-channel version? Absolutely. There are certain advantages, however, with some familiarity of the essential moving parts. The two-screen edition expands on Glenn Kenny’s prescient comment in the New York Times during the reissue a few years ago that Personal Problems provides, “among other things, that cinema retains the ability to accommodate the noncategorical.” What if General Hospital or The Days of Our Lives were repopulated with an almost-entirely-Black cast in non-stereotypical roles? How would the landscape for Black filmmakers have changed if PBS has picked-up this series — and continued it — way-back-when as initially intended? It is precisely Gunn and Reed’s approach to this tale that makes it relevant in a way entirely unlike any other soap opera produced in the 1980s. It transcends the disposability of any plot to display the reality of its time.

— Jonathan Marlow (@aliasMarlow)