A Conversation with Traci Curry & Stanley Nelson (ATTICA)

In their new documentary, Attica (which I reviewed out of TIFF 2021), director Stanley Nelson (The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution) and co-director Traci Curry examine the history and legacy of the 1971 prison uprising at the Attica Correctional Facility in upstate New York. Using a wealth of archival material and present-day interviews, the two construct a precise timeline of what happened when and how things turned so violent. It’s gripping, harrowing stuff, offering the viewer a front-row seat to America’s deeply problematic system of mass incarceration (then and now). Fans of one-time New York governor Nelson Rockefeller (if they exist) will be disappointed (tough luck), but everyone else will be riveted. The film is now playing both on Showtime and at DOC NYC. I spoke with Nelson and Curry a few days ago by Zoom, and here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity

Hammer to Nail: To me, Attica has always been associated with Al Pacino holding up his fist in Dog Day Afternoon, going, “Attica! Attica!” So I’m really glad I got to learn a lot more about what happened. Thank you for making the film. How did the two of you pair up?

Stanley Nelson: Traci worked on two or three other films that we’ve done in a row. It was pretty much one right after the other, and Traci’s a fantastic producer/director. Attica was really an important film for me because it was one of those films that I had been thinking about forever and I wanted it to be done right. And I mentioned it to Traci, and Traci can take it from there.

Traci Curry: I kind of knew, Chris, what you did, which is the Dog Day Afternoon film. Honestly, I don’t even know that I’ve ever even seen Dog Day Afternoon, but I know that scene. And so, it was interesting to me to find out what it is about this event that is so resonant in the culture. I guess the invocation of it, with that word and that scene could kind of bring up all of these issues and everything that they were trying to communicate there. And I knew that whatever happened, the little bit that I understood about it was there was an uprising in upstate New York and it involved issues that I personally am always interested in exploring through storytelling, like state abuse of power, law-enforcement abuses, the prison system. So I knew that if nothing else, it was going to be an educational and deeply interesting journey, making this film.

HtN: As co-directors, how did you divide the labor? I’m always curious when people work together, who does what or how that works.

SN: One of the things that happened for us is that COVID, really, dictated how we work. In the beginning, I was going to do some of the interviews and Traci was going to do some. I really can’t remember. And then, when COVID struck, I’m obviously a lot older than Traci and I felt, at that point, that I didn’t want to travel and do interviews. And Traci really kind of took over and did all the interviews.

TC: Yeah. I mean, I was really happy that Stanley trusted me with the opportunity to be able to take the time to look for and really talk to all these people. In some ways it was a little, this is weird to say, but a little bit helped by the pandemic. Because I, as we all were, was alone in my little home pandemic box and it really just gave me the time and space to figure out who, 50 years later, is even still around to tell the story, and then to figure out the scope of all of these various kind of players in this story, whether it was the prisoners or the people of Attica village, the media, etc. And then, to really take the time to kind of dig in, look through public records, look through media reports of the time, look through transcripts from the three decades of lawsuits that happened after. Figure out who might still be around with a story to tell and then really take the time to try to find those people. And then just get on the phone with them and really begin having some of those early conversations.

HtN: Your film features such great archival material and until I figured out that some of it was coming from the news crews, I was scratching my head, thinking, “Where is this footage coming from? This is amazing!” But even though it was shot by news crews, it still must not have been easy to get access to it. So, what was the challenge like of gathering this archival treasure trove for your film?

SN: Well, I think the challenge of the archival was multiplied because the whole film was done during the time of COVID. Many of the archives shut down or would have one person there one day a week or it would just be a lot harder. But we knew from the beginning that there was some archival. We knew that and we then just pressed and pressed and pushed and pushed to get all the archival that we could. And it sounds easy, but it’s not, because the networks, they’ll have a tape of kind of the greatest hits from Attica and when you ask for the Attica footage, that’s what they’ll send you. And you say, “Well, there must be more, there’s got to be outtakes. What about the outtakes?” And then they would say, “Oh, our warehouse is closed and there’s nobody there.” And you just have to really push and keep pushing for them to give you everything.

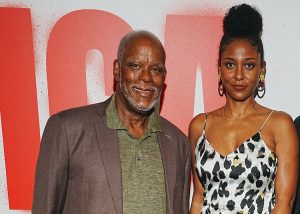

(L-R): Directors Stanley Nelson and Traci Curry at the ATTICA premiere. Photo Credit: Ben Hider/SHOWTIME.

And we said, basically, that we wanted to see everything. That’s the way that I look at it, that we want to see everything. We’re not going to worry about the cost while we’re trying to get the film together, we’ll cross that bridge when we come to it. So that’s what we did. We just had a great archival producer, Rosemary Rotondi, who every day for a year and a half or so was trying to find footage, trying to get into the archives, and trying just to get the best stuff. And then when we kind of finished the film, we went back to ABC, NBC, and CBS, the three networks that really existed at that time, and whenever they had 16mm film, we went back and had them re-transfer the 16mm. And that’s one of the reasons why the stuff looks … I mean it just looks great; it looks like it was shot in Hollywood somewhere.

HtN: Traci, you were talking about reaching out to the people to see who was still alive to be in the film. What was that process like? Those are some moving interviews, particularly as the film goes on.

TC: Well, the early stages of it were really just kind of getting on the phone with people, having some of those first awkward initial encounters where you’re essentially asking someone to recount the most traumatic event of their lives from 50 years ago, in great and searing detail, to a total stranger. And certainly there were some “no’s” and some hang-ups and some, “Why are you bringing this up?” But fortunately, I was able to get in contact with enough people who were courageous enough, and gracious enough, to really go there and sit in it with us. And from there, it was just a matter of, before we ever got on camera, just kind of having those conversations with people and really stepping back and allowing them the space to remember and experience it, re-experience it in the way that was true for them.

So there were very few conversations, even the on-camera interviews, where there was not a lot of crying, rage that still was very much there, the shame of the way they were dehumanized that day, the injustice of it. All of that stuff, once we sort of got past some of that initial throat clearing, was very much there at the surface for all of these people. And I just saw my job as kind of creating the space for them to be able to express it however they felt it, and share those memories and kind of get out of the way and let them do that. And it’s funny, because people ask me, “Oh, was there something that you did to kind of get that, what you see in the film?” And in some ways, that is how those people came to us and some of it was just luck, because these people are so compelling and their memories are so clear and so honest and authentic.

HtN: Well, you did a great job because those interviews are really quite moving. So, I’ve always thought of Nelson Rockefeller, from the little I know about him, as sort of this benign, moderate figure, an old-style Republican like they don’t make anymore. But your film makes a really compelling case that he basically was a spineless villain in this whole episode. So, not such a benign figure. That was a surprise to me. What surprises did you discover in making this film where you went, “Oh, I had no idea”?

SN: I like “spineless villain.” I think that’s a good description of Rockefeller’s role in this. I mean, I think that the calls between Rocky and Nixon are surprising. I mean, they’re just incredible. We knew that the second one existed, the “was it the Blacks” kind of call after the retaking of Attica. But I had never heard this stuff before where, basically, Nixon is telling Rockefeller not to go up there, and really get an idea how Nixon is pulling the strings right behind the scenes. He’s not only just calling to congratulate, but even before, he’s behind the scenes. So that I think was incredible to me. And then some of the footage after the retaking, of the men being made to crawl, and crawl through the latrines, and some of those things are just shocking. Also, the pictures of the nude men with their hands on their heads, that’s just …you can hear a gasp go up every time we show the film.

TC: Yeah. I think so much of what was probably shocking to me was the way in which what actually happened defied what we might expect. Right? So Stanley mentioned that day of the retaking and you just don’t expect that your own government is going to come in and brutally massacre you; certainly not three dozen of its own citizens. But I also think what most people, I think, would expect when a thousand prisoners are allowed relative freedom within a prison to do whatever they want is that there will be chaos and violence and disorderliness. And certainly, in the early moments of the rebellion, there were all of those things. But I think I was so kind of surprised and impressed by how quickly the prisoners were able to recognize a political opportunity that they had in this moment to get the changes that they wanted to see in the prison. And how rapidly they were able to create order out of the chaos and kind of build this little democratic society. I thought that was extraordinary. And certainly something that defied what I would’ve thought and expected in that situation.

A still from ATTICA. Photo credit: Courtesy of SHOWTIME.

SN: I think that also one of the things that I learned was the real reason why the prisoners rebelled. That there were real shocking reasons, the way they were treated, the small things of only getting one roll of toilet paper a month to the bigger things of taking beatings with no repercussions at all. I think that was something that I didn’t know. And I feel like most people don’t know that it wasn’t just, “Oh, we’re mad because we’re in prison.” It was that they were being treated like something less than human at Attica. And that’s why they rebelled.

HtN: I saw your film at Toronto where I also saw Stefan Forbes’ Hold Your Fire, which is about the 1973 Brooklyn robbery that turned, not into a bloodbath like Attica, but still into a bit of a fiasco on the police side. In that film, Forbes makes the compelling case that that robbery, coming on the heels of the Attica uprising, led to the development of hostage-negotiation teams. So Attica is part of that progression, as well. What are some other legacies of Attica, today?

TC: Well, before Nelson Rockefeller goes on to become Vice President of the United States, we know that he then passes these draconian Rockefeller drug laws, right? Which are then replicated across the country, which then help to fuel the explosion of not only the prison population, but also the building of the ridiculous number of prisons that we have at this time. So I think that there’s a direct connection between that and where we find ourselves now, because as you mentioned in the beginning, Chris, I think everybody saw Rockefeller as this sort of benign, progressive Republican figure, which was not the way that you got elected at that time. You had to follow the Nixonian blueprint. And I think what Rockefeller recognizes after Attica, after he gets to look like this tough-on-crime, law-and-order guy, is that he gets political currency out of that. I think there’s a direct connection between what happened at Attica and where we find ourselves today in the United States, where we have the largest population of people in the prison system among developed nations in the world.

SN: I think that whatever gains were made in the prison system, it’s offset by the fact that there’s 2 million people in prison now, so that the prison population has exploded. So they might get more than one roll of toilet paper a month, maybe there’s some educational programs, but that’s way offset, way weighed down by the fact that there’s now 2 million people in prison.

HtN: Well. thank you so much, the both of you, for making this film, and thank you for taking the time to chat with me.

SN: Thank you so much.

TC: Thank you!

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)

Showtime; Traci Curry and Stanley Nelson; Attica documentary film interview