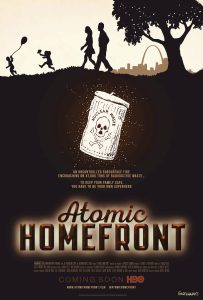

A Conversation with Rebecca Cammisa (ATOMIC HOMEFRONT)

I met with documentary director Rebecca Cammisa, on Friday, June 16, 2017, at AFI DOCS 2017, to discuss her new film Atomic Homefront (reviewed here), which takes a probing look at a St. Louis community that has long been contaminated by radioactive waste dating back to the 1940s. At the heart of the story is an SSE (“Subsurface Smoldering Event”) – i.e., a fire – in a landfill, next to a residential area, that also contains some of that radioactive material. It’s a heart-rending profile of loss and resilience, anger and hope, that refuses to back down from its condemnation of government inaction. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation.

Hammer to Nail: You have directed two prior feature-length documentaries, Sister Helen, in 2002, and Which Way Home, released in 2010 and nominated for an Oscar. The short documentary you made after that last film, “God Is the Bigger Elvis,” was also nominated for an Oscar. Do you see any kind of dramatic through-line in your work, film to film? If so, how does Atomic Homefront fit into it?

Hammer to Nail: You have directed two prior feature-length documentaries, Sister Helen, in 2002, and Which Way Home, released in 2010 and nominated for an Oscar. The short documentary you made after that last film, “God Is the Bigger Elvis,” was also nominated for an Oscar. Do you see any kind of dramatic through-line in your work, film to film? If so, how does Atomic Homefront fit into it?

Rebecca Cammisa: I suppose I like to make films about people who either don’t have political power or maybe aren’t the most financially well-off, who usually don’t have a voice, or usually aren’t given validity. The through-line that each of my films has in common is that we spend time with people who aren’t paid attention to, whether the story has never been reported or isn’t well known, to just people who who have never been asked the question “How do you feel?” or “Why are you doing this?” (laughs) You asking the question has made me think about what am I attracted to.

HtN: The disenfranchised.

RC: Well, a term like that is already a bit, you know…those people know a lot, and usually what they fear most is actually the case, and what the authorities say is the case often turns out not to be the case. So, I think one can learn a lot from regular people, on the ground, who live the reality they are living.

One thing, in particular, in Atomic Homefront, is that there are quite a number of cases of appendix cancer, and appendix cancer is rather rare. So, the fact that there is quite a bit of appendix cancer in one particular zip code is, I think, something worth looking into. I wasn’t aware of appendix cancer. I’ve asked some doctors since then – some oncologists – and they weren’t even aware of it. And so I’ve learned about this cancer in St. Louis, and one has to scratch one’s head and wonder why there are so many cases of such a rare cancer in one particular area of the country.

HtN: And your film asks those questions, and makes it very clear that we should all be asking them. So, you came across this story in 2014. At what point did you know that you had to make this as your next film?

RC: I was told about this story by a geologist. He told me a couple of things that made me think, “OK, there’s definitely something to this.” But you always go into stories like this wondering if what people are afraid of is really scientifically possible. Is it potentially true? And the more we really looked into it, the more we realized that what they were saying could very well be the case. And that just kept piquing my interest, making me want to go deeper and deeper and deeper.

In the case of the film, you have members of the public that believe something; then you have a corporation labeling them as activists, calling their beliefs suppositions and hysterics that are infecting a community; and then as time goes on, you realize that every fear that these people have has, indeed, come true: they weren’t being hysterical at all. And yet, the corporation that was accusing them of this very carefully used certain buzzwords to be able to marginalize these people, instead of seeing them for who they really were: concerned citizens. So, just listening to the language of others, and then speaking to people in the scientific community to see if it were possible, and then learning more and more about the facts and the nature of this very toxic site, allayed our suspicions. We knew that what people were afraid could potentially have taken place.

Our Christopher Llewellyn Reed and director Rebecca Cammisa

HtN: So, along those lines, many of the people in your movie are ill and/or angry at the way they and their community have suffered because of the callous way our government has treated them. Did you have any difficulty convincing any of them to be in the film, or were they all eager to tell their stories?

RC: Well, I don’t believe in convincing people to be in a film. I’m a documentary filmmaker. My films will be, hopefully, broadcast, so they’ll reach a large audience. And people have to be psychologically prepared for what that means. So I never try and talk people into being in my films. I speak to them about the issue and why I would like them to be in it, and what it would be like if this film becomes popular or gets broadcast, and people get to decide for themselves. We had a lot of people we went to who didn’t want to be part of it, and we stepped away and said “thank you,” anyway.

A lot of the people that we approached, however, were really welcoming and wanted to film with us, because it validated what they were trying to get others to believe. And, as time went on, we still weren’t sure whether this was really taking place, whether what they were concerned about was happening. But then, as each day and month went on, the truth was revealing itself, even though there were a lot of institutional controls trying to keep that from happening.

I will say, though, that the Army Corps of Engineers was the one entity that filmed with us, and allowed us to film them, and conducted interviews with us. And the Army Corps of Engineers is on the ground, actively remediating radioactive waste; that’s what their FUSRAP program is about. So they were very forthcoming with us, and we didn’t have to convince the Army Corps; they were there for a reason. They know these radionuclides are there, and it’s their job to dig them out and get them out. So it’s not like the community totally wasn’t believed about toxicity, but as time went on, the level and extent of it was becoming more and more acknowledged.

HtN: So, I am sure that some of the footage was more difficult to film than others. At one point we are in a hospital with a young man who is dying of cancer. Another, adult, character in your film is similarly sick. What were some of the hardest parts of the film to deal with, for you?

RC: You know, in terms of our young man, Jonas, who died at 16 years of age, we had never met either him or his mother, previously. We were connected to them on only our third day of filming in St. Louis. Someone reached out to Jonas’ mother, and she wanted us to come and see him, so we drove across the state. Here’s this 16-year-old boy, clearly dying, and I spoke to him, saying, “I know we drove all this way, but if you don’t want us to film you, we don’t have to.” And he turned his head a little bit and asked, “Do you think it’ll help?” And I was about ready to fall apart. I said, “Jonas, that’s why we’re here, because we think it could help.” And he said, “Then let’s do it!”

Here’s a young man, and his mother…his mother didn’t know if he was going to make it through the weekend or not, and yet they spent a precious hour of their time together with us. And so the hardest part, for me, was not that particular moment, but rather when the EPA [Environmental Protection Agency], or other agencies like the Missouri DNR [Department of Natural Resources] wouldn’t spend a similar hour with us to talk about things. I found the times being rejected – of people refusing to film with us – harder because, from a journalistic standpoint, we wanted to give everyone a fair shot to speak. We wanted to understand everyone’s point of view; we wanted to fairly represent everyone. But when we had the supposedly most powerful institutions and agencies refusing to give us any time, and then there is this young boy who is dying – maybe within days – saying, “Yes, I’ll give you my time”…that really hit me and I thought…he’s a great example to follow, and they’re not.

HtN: Yes, well, I’ll admit that I was surprised by the recalcitrance of the EPA under the Obama Administration, including its then-head Gina McCarthy, to deal with the clean-up of the radioactive waste and to talk to the local residents, or even you. I can imagine it could be worse there now, under the current EPA head. Have you followed the story since you finished your movie? How are things in St. Louis now?

RC: Well, I would love to forward you all the news stories since I wrapped the film, because otherwise this would be a 20-minute answer. But basically, I have kept up on what has happened there. It’s just so much, from the attempts to get the State Senate to do a buyout for the people in the community of Spanish Village, in St. Louis, and how that fell apart, to what form will the EPA be in now and what will be left of the Superfund program and what are [current EPA head] Scott Pruit’s true intentions; does he really know what’s going on there? And in terms of the regional and national offices, does the right hand know what the left hand is doing? These are still questions I have. So yes, I have kept abreast of what is going on, but we did have to end the film at some point. So a lot of what is going on now is not in the film.

HtN: What about the SSE?

RC: From what I understand, the Subsurface Smoldering Event is now closer to the radiation. What’s interesting is that in the one of the two contaminated areas – OU1 [Operating Unit 1] – the EPA remapped, and found that the radiation had migrated further south, so forget the fire getting closer to the radiation, the radiation is actually getting closer to the fire. So my question to the EPA – one of the few questions they ever answered – was, “Are you remapping OU2?” And they said, “No, we have no plans to do that.” And I asked, “Why?” And their answer was, “We just don’t have any plan to do that.” It begs the question, if you see radioactive migration, or the migration of radiologically impacted materials, in one area, why wouldn’t you check the second area to make sure that isn’t the case there, as well? Or if it is the case, how much closer is it to the fire? So, who’s minding the store, is ultimately what I wonder on a daily basis.

HtN: And it’s pretty amazing, the level of obstruction and stubbornness that we see in the film. So, final question: you have quite the crew of cinematographers. You have a DP [Director of Photography] and then four additional camerapeople, including yourself, and including Kirsten Johnson, director of Cameraperson. How did you assemble your team?

RC: Well, actually, when we first started filming – when we got a little bit of money in, and did our first couple of shoots – Kirsten Johnson was filming. And then it took some time to raise more money to get back into the field, and by then Kirsten was doing Cameraperson, in addition to all the myriad other projects she’s doing, so she wasn’t available. So I contacted Claudia Raschke, whom I had worked with previously, on God Is the Bigger Elvis – she’s fantastic – and then in addition, we worked with Ron Chapple, who did those amazing aerial shots. Those are not drones. That’s real aerial cinematography.

HtN: They look great!

RC: So that was exciting. And also, we were doing our jib shots, and our other specialty shots with Thomas Newcomb, who is a St. Louis cinematographer, and we also had Ryan Dorris – another St. Louis cinematographer – and myself. So, it was quite a few of us over a period of two years, on and off.

HtN: That’s how long the production was? 2 years?

RC: We started filming in August of 2014, and the last shoot we had was in November of 2016.

HtN: So a little over 2 years. Well, thank you very much. Congratulations on the film!

RC: Thank you so much!

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)

Kevin McDaniel

As sorry as I am for these folks, Missouri (and esp St. Louis) voted overwhelmingly for President Trump, who has called the EPA a farce, and gutted it. Why isn’t Trump mentioned in your documentary, and what’s happening with our environment and environmental enforcement under this administration? At the Security Policy Institute, we named environmental issues as the #2 threat to humanity in 2016, based on scientific research. It disturbs me greatly when people vote for someone who clearly has an agenda the disavows public policy about environmental concerns (as fake news) and then complain about their environmentally triggered health problems. You got exactly what you voted for! Dr. K. McDaniel.

A Musol

Get your facts straight. The final scene of the documentary took place in 2016. The site was designated a superfund site in 1990. This entire documentary took place during the Obama administration, who did nothing. On Feb 1, 20178 the Trump administration approved the partial removal of the contaminated waste, the first significant action by the EPA in over a decade. https://www.epa.gov/superfund/superfund-sites-targeted-immediate-intense-action

You do get what you vote for.