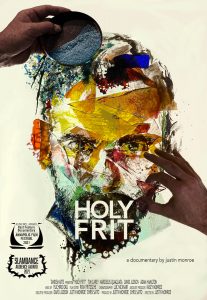

A Conversation with Justin Monroe & Tim Carey (HOLY FRIT)

As I did in 2020, I moderated a number of virtual Q&As for this year’s Annapolis Film Festival. One of them was with director Justin S. Monroe, to discuss his documentary Holy Frit (which I reviewed out of Slamdance 2021). Joining us was lead subject Tim Carey, whom Monroe follows in the film as he designs and builds what will be (if completed) the world’s largest stained-glass window. It’s a commission for the United Methodist Church of the Resurrection in Leawood, Kansas, whose pastor is Adam Hamilton, and the stakes are high for both Carey and David Judson, who owns and manages the studio where Carey works. We learn quite a lot about the art and craft of stained glass in the film, including the relatively new technique of fusible glass, pioneered by Narcissus Quagliata (who also appears in the film). It’s a fascinating look at a little-known process, and well worth a watch. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Hammer to Nail: I really enjoyed the film. I knew nothing, not only about the traditional art of stained glass, but about this newfangled thing that you teach us about in the documentary. So, I’d like to start with a pretty basic question, which is for you, Justin, how did you discover this topic, this story, and what part of it came first to you?

Justin Monroe: Well, you know how it happens, sort of inspiration comes from on high and just says, “Do this thing.” (laughs) No, actually, it’s pretty funny how it happened. I moved from Oklahoma back to South Pasadena, which is outside of Los Angeles, and serendipitously moved next door to this nuthead. (indicates Tim Carey) Never knew him before. And we were neighbors. We became friends and he told me about this crazy project that he was doing, the biggest in the world. And the fact that they looked like they were going to land it. They were getting really close. And that he didn’t exactly know how to pull it off. So, I went, “Wait a second, hold on now. This is very interesting.” And then he asked me to come down and shoot a promo to go with their final pitch to the church. And so, as I was shooting the promo, I got more and more of an understanding of the project. And I went, “You guys, we have to be filming this. We have to be filming this.” Tim was on board and I had to convince his boss, David, and David said, “All right, let’s go for it.”

HtN: That would be David Judson, right?

JM: That’s right.

HtN: Well, so you really were – and this is not always the case – right there from the start.

JM: I was. And I don’t know how great of a thing it was for Tim, because I was almost just lying in bed next to him. I was there all the time. (laughs)

HtN: Well, we see in the movie, Tim, that you have a very understanding and supportive family. And now I think even more highly of them since apparently Justin was literally sharing the bed with you. (laughs) So, Tim, what was the experience like for you? Did it live up to your expectations? Did it surpass them? What kinds of expectations did you have when Justin decided he was going to make this film?

Tim Carey: Well, when I entered the company that I worked for, Judson Studios, I knew nothing about stained glass. I think that, like you and maybe everybody else who I’ve ever met in my entire life, people know what stained glass is. If you say “stained glass,” everyone goes, “I know what that is.” And usually it’s followed by, “I have an uncle who does this,” or “I have a cousin who did it,” or “my aunt in her garage, but I don’t really know how it’s done.” So, when I jumped into it as an artist who was trying to have a career as a painter, I was like, “Holy s***, not only do I now know how this is done, but I want to do it myself. And I think it’s beautiful and fascinating. And it’s totally untapped.”

That was my initial approach to stained glass, getting my job. And so then, as I worked for years and years and years, I was always, in the back of my mind, being a younger person in this kind of old-world, traditional technique, thinking, “This is beautiful. Why have I never seen anything on TV or everything we ever see about stained glass is like some old, ‘Oh, here we are with the stained-glass windows of York’.” I just always felt like it was a stodgy old thing. And when Justin talked about starting to shoot it and filming, I was like, “Yes, we should film this. This is amazing. People need to understand this.” Not only is it beautiful in and of itself in the traditional way, but it’s beautiful in the sense that I think we can do more with it as artists.

So, I was excited. I always felt that it had some potential, visually, as a medium for film and for something that just … it’s kind of an easy mark. The glass already is beautiful and then you add the story to it. It felt like a natural fit. The hard part, I guess, was getting used to having cameras all around, all the time. But over time, I got used to it. And when Justin would come into the bed at night, we would talk about it, but he would help me to understand, while he was scratching my back at night in the bed, how it was going to work as a film and as the director. (laughs) And so we got a rhythm over time.

HtN: Well, I have to say, speaking of that learning curve for the audience about how to make stained glass, what makes your film especially engaging is that you have a built-in dramatic arc right there. I still don’t quite know if I understand exactly how frit makes the fusible glass somehow look so beautiful, but I feel like I got a lot of really great information and it was such a fascinating process to watch.

JM: Yeah. It’s funny: if you would have asked me before – this has been going on almost six-and-a-half years – I never, in a million years, thought I’d be doing a film on stained glass. So, to me, what drew me in were the characters. I just thought these are such amazing, interesting people, with the premise being that they don’t know how to pull this thing off. It can’t be replicated in traditional stained glass and that’s what Judson knows. And so, they have to call in the help of somebody who’s a famous artist who they have never even talked to yet, named Narcissus, of all names in the world: Narcissus Quagliata. And then from that point, I fell in love with the glass. And so, what an interesting thing to be thrown into, the first of its kind, too. That’s what I find to be very interesting about the whole thing.

HtN: One of the really fascinating elements in the documentary, Tim, is your relationship with Narcissus, which is occasionally fraught, but at other times, it’s like mentor-mentee. How did that evolve for you?

TC: In an instant, in one day of spending time with him in our workshop, we connected. We became best friends and artistic buddies. We had the same kind of aesthetic interests, in terms of art history and what we liked. I found out on the first day that he was working with some of the artists that I love in the Bay Area during the figurative movement in the ‘60s and ‘70s. And we were kindred spirits from day one, even though we’re 30 years apart.

You meet your best friend and they’re 75 years old when you’re 40. That’s how it felt. We just got along. I felt like I could say anything to him. He could say anything to me. We could get mad at each other. We could fight. But at the end of the day, we came together. He was artistically just avant-garde in all these ways and I was much more of a traditional nerd about this stuff. So we had these really great balancing traits. And yeah, we still talk to this day. We text, we talk. He’s in Mexico and we will forever be connected in these techniques.

And now, what we’re trying to do is find other artists that want to do this. And we feel like we’re trying to be ambassadors for something that he’s been doing for forty years and I’ve been doing for five. But now he’s got me on board. We did have friction, obviously, at certain times, but that friction never lasted. We would come back together because we had this common goal of doing this project and doing a great job.

HtN: Indeed, it seems that way. Justin, what was it like to suddenly have this larger-than-life figure? Everyone, up to that point in the film, is already filling the screen quite well, but what was it like to have this other element suddenly thrown into the mix?

JM: I was nervous because I knew we needed Narcissus to be on board for this thing to work. And with a name like Narcissus, you don’t know what you’re going to get. So we made sure to tell him ahead of time, “Just so you know, when you arrive, there are going to be cameras in your face.” And we were holding our breath, like, is he going to be okay with that? And Narcissus had been interviewed a ton of times in a lot of different ways and had done another documentary based on him when he did a dome in Kaohsiung, which is incredible, by the way, if you haven’t seen it. It’s insanely amazing. And so he’s just very comfortable on camera and he said, “No problem.” We became very close, he and I. And so along the way, actually, I was able to film him, and I still am. We’ve been kind of shooting off to the side and getting his life story from 19 years old, all the way to where he is right now, how he developed as an artist.

HtN: Would that be your next film: “Narcissus: The Movie”?

JM: (laughs) Right, right. I think it’s, as of right now, “Facing the Monster,” which is himself. And I think that is what Tim had to face in himself, where you look into a mirror and you realize, “Can I pull this thing off? Do I have what it takes?” And Narcissus, as amazing as he is, was very vulnerable with us and very honest. I found that to be incredible, such a huge personality, but yet so truly vulnerable. He’s a real artist and he faces the monster all the time, just like the rest of us.

HtN: Justin, one of the things I really liked about your presentation of the material is your use of a variety of split screens. It clearly mimics the different ways in which stained glass also splits the image. When and how did you come up with that technique for your movie?

JM: You know how you wish you could say that this amazing vision came? But it was a practical thing. Obviously you understand how the lead splits the image and so I knew about that all along and I love that about it. And I thought about different ways, but I had … this is embarrassing. I shot so much footage. If you’re a filmmaker, you’ll laugh at me. I shot 1100 hours of footage. 1100 hours! (laughs)

HtN: That’s quite the ratio.

JM: And I knew I needed to whittle it down into, well, I was hoping for like an hour-and-a-half. Unfortunately, we didn’t quite get there: it’s just under two hours. But it was sort of a practical way of figuring out how to find ways to show imagery at multiple times and have multiple things happening at one time and still always communicate the same narrative. I’ve been inspired by movies that have done that very well. And so it was a practical response to a need, is what it was.

HtN: Well, I think it’s a really brilliant technique, given the subject matter. Tim, one of the things that is really impressive in the film is your work ethic and how devoted you are to getting the project done. As I said in the beginning, you also have a very understanding family. Do you find, with your current projects, that you have more free time in terms of work-life balance? And I speak as somebody who has terrible work-life balance.

TC: Wow! That is a really good question. I feel that if my work ethic comes across as strong during the film, then that’s just great editing. (laughs) Kudos to whoever made it look like that because, I don’t know, I’ve never been the one who feels like I’m burning the midnight oil. In fact, during the movie, Narcissus had to say, “You should just cut off your family.” There’s one point where he just says, “You should not see them.” And I was like, “I kind of like … it’s sort of fun playing Little League and stuff.” But obviously, for that project, it required a little bit of tunnel vision.

Filmmaker Justin Monroe

Now I have my own company and I’m doing my own thing. I’ve had to work a little harder on compartmentalizing everything. It was to some degree easy with this big project because you have no choice: you have this deadline, it’s sitting there, you have to get it done and there isn’t really an option. Whereas now, when I have a project, for the most part, with glass, it’s a luxury item. It’s not a deadline. No one says, “Oh, I need to have this by this date otherwise my house isn’t going to stand up.” It just is a beautiful thing that I’m making and I’m doing it at home. My studio is at home.

HtN: Do you think the church will ever arrange for those speakers in front of the window to be removable? I’ve watched the movie and I know you touch upon this, but I still cannot fathom why that would not have been a priority to make those speakers retractable.

TC: There was a time, and it’s in the film, where I say, “Is there an option that maybe the speakers can be retractable?” And I was still very sheepish because we didn’t even have the job yet. And now I watch that and I go, I wish I would have just looked at the guy and said, “You are Adam f***ing Hamilton. There will be no speakers in front of this window. Make it happen. Somehow, some way, somehow make it happen. Like that’s what you do. You are the biggest and the best.” And I didn’t do that. And I wish I would have, because they were convincing me the engineers couldn’t do it. And I just wasn’t buying it. And I knew that it was going to be something that was going to be a problem. And I wish I would have pushed harder. But it’s honestly not as bad in person as it is on film. If you see the window in person, you walk in there and the speakers initially jolt you, but then you kind of move underneath them. In three dimensions, everything kind of flows. But I do wish I would have pushed a little harder.

HtN: Well, irrespective of the placement of the speakers, your work is truly impressive. And I think that that stained glass, especially involving a technique that you were not familiar with at all before you took on the project, is a monumental work and you should be proud of it, as should everyone who was involved. So, congratulations on that.

TC: Thanks very much.

JM: I have to tell you, but I’m sure you know this: a camera cannot do it justice. It just can’t. Seeing it, truly seeing it and actually being able to go up behind it and standing next to this towering thing, it’s like, you’re literally enveloped by a basketball court. That’s what it’s like: a basketball court of glass. It’s hard to even describe how it feels. On a macro scale, it’s huge, but to be able to get in close, every single piece of glass was a beautiful thing unto itself because of this technique. It’s a mosaic of broken things that makes this beautiful monument. I just find that to be such a telling thing, almost, about humanity. I think that’s how we are, how art is, how making a movie is. It’s all these edited little bitty scenes, these edited little bitty moments that make up this tapestry. I found that to be such a similar narrative to life, to what we do.

HtN: Kudos to you for putting it that way. Your film is many things, including a testament to the human spirit and the human striving to create art and to express ourselves in these profound ways. Gentlemen, I want to thank you both so much for chatting with me. I wish you both great things in both personal projects and this movie.

JM/TC: Thank you.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)