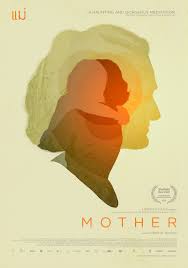

A Conversation with Kristof Bilsen & Kirsten Johnson (MOTHER)

I met with director Kristof Bilsen (Elephant’s Dream) and executive producer Kirsten Johnson (Cameraperson), on Sunday, November 10, 2019, at DOC NYC, to discuss their collaboration on Bilsen’s new documentary Mother (which I also reviewed). In the film, Bilsen tells the parallel stories of Pomm, a caretaker in Thailand who works at a center for German-speaking Alzheimer’s patients, and a Swiss family forced to consider options of where to send their mother, Maya, now afflicted with the same disease. Exploring the divides of class and country that offer very different choices to different people, and the cost of these choices on families, Mother is at all times a complex, deeply affecting story. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

I met with director Kristof Bilsen (Elephant’s Dream) and executive producer Kirsten Johnson (Cameraperson), on Sunday, November 10, 2019, at DOC NYC, to discuss their collaboration on Bilsen’s new documentary Mother (which I also reviewed). In the film, Bilsen tells the parallel stories of Pomm, a caretaker in Thailand who works at a center for German-speaking Alzheimer’s patients, and a Swiss family forced to consider options of where to send their mother, Maya, now afflicted with the same disease. Exploring the divides of class and country that offer very different choices to different people, and the cost of these choices on families, Mother is at all times a complex, deeply affecting story. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Hammer to Nail: So Kristof, let me start with you. The film ends in loving memory of your mother, who died this year. Is there any connection between her and the story in any direct way?

Kristof Bilsen: Yes. The whole motivation to make the film was definitely thanks to her, I would say. I lost my own mother to dementia, and so the whole process, for me, took off almost 10, 15 years ago. It’s a very slow process. The deterioration is very much almost invisible, and then more and more visible, sadly so. Seeing my father suffering, being in informal care, and me and my siblings saying, “OK, this not going to get any better. So, is there any way to go about caring for my mother? What are the options these days? What is out there?” And while I was researching that, I stumbled upon this place in Thailand. Not that I would bring my mother there, she wouldn’t allow me. But she knew about the film. While I was working on the film, she was very aware and very present in the process of what I was going through.

HtN: So, from there, how did you decide to center your story on Pomm and the Swiss family?

KB: Initially it was for me an exploration of space, the space of where the Alzheimer’s patients and dementia patients reside in Thailand. And then, quite soon, while I was researching and pre-shooting, I encountered Elizabeth, the old lady you see in the film as well, who was taken care of by Pomm. She’s kind of charismatic, mysterious. There was a lot of mystery to her. I was attracted to the real, genuine interaction between the two of them. So, we felt that it spoke very much to motherhood and care on the most universal level rather than sort of pigeonholing it into this sort of disease, if that makes sense.

HtN: And then how did you find the Swiss family, which then perfectly lines up with Pomm, since their mother, Maya, ends up in her care?

KB: Yeah, I would say it’s serendipity in a way. I mean, I knew that we ideally wanted to follow a patient all the way from Switzerland to Thailand, just as a narrative arc. But then quite soon the man running the center, Martin, said “No way,” because the people who are in the middle of that decision are stigmatized, traumatized, losing a lot of friends along the way, a lot of family members even, because the ideal is you have to do it at home, you have to give the care at home. That’s how it works. And if you don’t do so, you’re ungrateful, et cetera. Up until one certain day, I said, “Well, there is a family of three daughters and a man who will send their mother,” and they were happy to meet. And I was like, “Yeah, sure, and then that’s going to end that story.” And so I showed them rushes I had made and told them told my own messy story, talking about my mother and they were like, “Yes, let’s do this.”

HtN: So, Kirsten, at what point did your own involvement begin?

Kirsten Johnson: You know, I think you must let Kristof tell the first part of that.

Kirsten Johnson and Kristof Bilsen (MOTHER)

HtN: (laughs) Back to you, Kristof.

KB: So, with Kirsten, I I know her work and the films she worked on, but then there was Cameraperson, and that, for me, was so mind blowing in those moments, those pockets of life.

KJ: Watching Kristof’s film is literally like touching the people in the film. We see this physicality of the people on screen. But I think what we understand as camerapeople, both of us together, is that your physical proximity to people when you film them is palpable on the screen. And so, in my long trajectory of doing camera work, there are many different ways in which you are able to be present. When Kristof reached out to me and sent me the link to the film, I honestly was just floored by his capacity to stay in incredibly emotionally challenging situations. The challenge of holding still with a camera in these really fraught moments, it’s extreme. And that’s what I saw in Kristof’s film that moved me so much, is he just stays in these moments where extreme pain is being expressed.

KB: You could see that as sensationalist, no? But the thing of staying in, I think that for both me and Kirsten, it’s like you stay because there’s a transformation happening and that’s what you see with Pomm. She’s using a video camera herself, doing a video diary where she’s also staying and filming excruciating moments, such as where she has to let go of her daughter for a while. That’s what I adore. These kinds of films where you see an image, but that image sort of folds open like a Russian doll.

HtN: So, Kirsten, in a movie like this, what is your role as an executive producer?

KJ: I think the first moment of connection between us, after I saw the film, was that we simply had a conversation about how I responded to the film. And Kristof had already done all the filming and basically done all of the editing. He had made the film. And I believe in a certain way that all that I did was simply recognize the work. And I don’t know in what way that was meaningful to you, Kristof, but all I did was to say, “You were right on. Leave the complexity in this film, leave that open space for the emotions to build and you have something really extraordinary here.” And for me that was it. That was all I did.

My hope, coming on board when Kristof asked me, which really felt like an honor to me was, is there a way in which I can help amplify this film being seen in the world and people paying attention to this film? Because one of the challenges with this kind of work is that people want to reduce it to an easy political story or a medical story. And I think we share the belief that this is a much bigger film than all of those things, even though it contains all of those things.

HtN: How do you handle negotiating access with people who suffer from dementia? What are the ethical implications of filming them?

KB: For me it’s, it’s very clear. I’m happy I can trust my ethical sort of instinct because my own mother was suffering from the same thing. So, in that sense we kind of agreed to a couple of little things that I wouldn’t film, such as embarrassing moments, showers, whatever, you don’t need those kinds of things. And I think with the patients themselves, it’s taking your time. With Maya, for example, she’s part of that process of making the film because we filmed her from Switzerland all the way up to Thailand and there’s an intimacy and it’s not an embarrassing intimacy. There’s a communication going, but like Kirsten said, it’s a physical communication. It’s not in words, but it’s a physical sharing of a space of emotions. We’re dancing that dance together, I would say.

HtN: Having Pomm film herself in the two different locations where her kids live was an interesting choice. How did you come up with that?

KB: It was initially just a good way for us to keep track of her story because I’m director and producer on this film and financing is also a very draining process and it was a very handy direct tool, like, “OK, what do you see, Pomm, what do you see?” Even if the camera would be extremely embarrassingly shaky, it would be a perfect sort of doodle of going into her mind and finding the poetry and the language and the pacing of her observations. But then she came back with this footage, which is like narrative beats.

KJ: Extraordinary footage. She’s an extraordinary cameraperson.

KB: She’s a cameraperson, so she’s a co-author of the film. And so that was how we knew that that was the voice that needed to be in the film. We couldn’t do it without Pomm.

HtN: It works really well. And speaking of the Pomm part of the story, your film is so complicated in terms of its socioeconomic layers. It’s still crazy to me that there is this place in Thailand to which people send their loved ones who are suffering from dementia. Such an interesting aspect of our world … But you choose to end your story on this image of Pomm’s youngest child crying as her mother is leaving …

KB: Crying and looking at the audience.

HtN: Crying and looking at the audience. It’s a very powerful moment. So, I wanted to ask you both about the choice to end that way.

KB: I think this film sort of extrapolates on such bigger themes of motherhood and care, which is super-universal. We often had, while making the film, this idea that everybody’s dependent on everyone. So it would be too colonial to say, “Oh, Pomm is dependent on the powerful West and the powerful West is dependent on Pomm.” Let’s shift those tables and shift that perspective and really see how much agency Pomm shows. You see that in bits, also, where she negotiates with her boss and really is trying to find her way. So, ending on that image, I think it’s a tribute from Pomm to her daughter and it’s a work that continues. It’s like the daughter will grow up and it’s a new generation thing.

KJ: I feel like one of the things that Kristof allows to exist in the film is this sort of structural inequity that exists, and the way in which it becomes very clear that the kind of care that dementia demands is almost impossible to give. What might be the structures that we could imagine that would support families and caregivers in this situation? Because it’s such a very peculiar experience to encounter someone with dementia and love them, whether you’re related to them or not. We’re aware of those structural inequities. We’re aware of a kind of injustice of the world. That means someone has to make a choice to work four hours away from her children, or six hours away from her children and only see them once a month.

But also, I think what the film does is talk about the ways in which choices that we make sort of amplify in different directions in time. So that, you know, for me, one of the things that really struck me about this film is that Pomm’s daughter is going to see it in the future. She’s going to have this film in the future to understand more of what the suffering of her life was. Right? We’re documenting the present, but it’s also, for the people in the films, a way in which they can understand their own lives. So I felt like that worked in many directions in this film.

So, the Swiss family will see this film and think about the choice that they made. And the thing that’s really powerful in the film is that everyone’s making impossible choices. You wouldn’t want to make any of those choices. And yet everyone must, and then they are dealing with the aftermath of the impossible choice they had made. And that feels like the most powerful part of the film. It’s that literally everyone is in an impossible position.

HtN: Well, I want to thank you both for making the film. It’s a really powerful testament to its subjects. Complicated, as I said, but really quite beautiful. So thank you.

KB: Thank you so much!

KJ: Right on!

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)

Like what you see here on Hammer to Nail? Why not pay just $1.00 per month via Patreon to help keep us going?