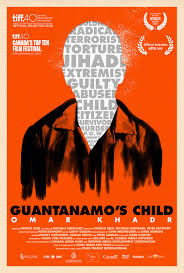

A Conversation With Peter Raymont (GUANTANAMO’S CHILD)

Guantanamo’s Child chronicles the harrowing story of Omar Khadr, a Canadian citizen abandoned by his Afghani father – who had possible ties to al-Qaeda – at a remote compound in Afghanistan in 2000. While there, he was filmed helping to make and plant an IED (improvised explosive device). Following a ferocious firefight with US Delta Force troops, during which the compound was bombed to rubble, Khadr was badly wounded. Accused of throwing a grenade that killed a US serviceman he was captured and, following internment at Bagram Air Base, was shipped to Guantanamo Bay. He remained there, without trial, for ten years, during which time he was brutally tortured and sexually abused. At the time of his capture, Khadr was fifteen years old.

Guantanamo’s Child chronicles the harrowing story of Omar Khadr, a Canadian citizen abandoned by his Afghani father – who had possible ties to al-Qaeda – at a remote compound in Afghanistan in 2000. While there, he was filmed helping to make and plant an IED (improvised explosive device). Following a ferocious firefight with US Delta Force troops, during which the compound was bombed to rubble, Khadr was badly wounded. Accused of throwing a grenade that killed a US serviceman he was captured and, following internment at Bagram Air Base, was shipped to Guantanamo Bay. He remained there, without trial, for ten years, during which time he was brutally tortured and sexually abused. At the time of his capture, Khadr was fifteen years old.

He plead guilty to murder in 2010 before a US Military commission (at which his lawyer, the indefatigable Dennis Edney, was not permitted to present evidence or refer to the torture Khadr had suffered) and was eventually repatriated to Canada where he served time at federal prison. He was released on bail in May 2015. Still regarded by some as an unrepentant terrorist, his conviction and treatment have been vehemently condemned by the United Nations. “Since World War II, no child has been prosecuted for a war crime,” Radhika Coomaraswamy, the U.N.’s special representative for Children and Armed Conflict said in a statement. Khadr represents the “classic child soldier narrative: recruited by unscrupulous groups to undertake actions at the bidding of adults to fight battles they barely understand.”

Simon Braund of Hammer To Nail spoke to the film’s producer, Peter Raymont at the Bermuda International Film Festival in March. A multi-award-winning writer, director, editor and cinematographer, Raymont’s previous documentaries have covered such uneasy ground as the Bhopal disaster and the Rwandan genocide. Guantanamo’s Child recently won the top prize at “Movies That Matter”, The Human Rights Watch Film Festival in The Hague and is also a huge hit on the international festival circuit. It screened briefly in a shorter version on CBC, SRC (French Canada) and Al Jazeera, and is currently awaiting theatrical distribution in the US.

Hammer to Nail: When did you first hear about Omar Khadr?

Peter Raymont: Omar has been famous, or infamous, in Canada for a long time. People know about the case, they know about him and they have strong opinions on all sides. I saw a Canadian film about Omar called You Don’t Like The Truth, primarily compiled of footage of him being interrogated by the CSIS (Canadian equivalent of the CIA) people who went down to Guantanamo. The footage of him breaking down and crying when they leave the room, it just broke my heart. I thought, Jeez, a film should be made about Omar Khadr with a proper interview with him.

HtN: How did you proceed from there?

PR: I contacted Michelle Shepherd who wrote the book Guantanamo’s Child and she agreed to collaborate. We bought the rights to her book and she became a co-director of the film with Patrick Reed.

HtN: What was your relationship with Patrick Reed?

PR: Par had made several films with me. He collaborated with me on Shake Hands With The Devil: The Journey of Roméo Dallaire (Emmy-winning, Raymont-directed documentary of the Rwandan genocide). So he was there with me in Rwanda as assistant director, and then he directed several other films that I produced. He’s a very experienced documentary director, so he was a great collaborator for Michelle, who’d been to Guantanamo twenty-eight times as a reporter with The Toronto Star, writing not just about Omar but the whole War On Terror.

HtN: Did you try to film with Omar while he was still at Guantanamo?

PR: We didn’t because we knew that would be impossible; no journalist interviews have been done with any detainees at Guantanamo, just lawyers. But we thought when he was finally repatriated back to Canada, after his case had been settled, that we’d be able to interview him in prison in Canada. That’s not unusual, but the prison wardens refused us repeatedly. He’d agreed [to the interview] but we couldn’t get in. So we took the government to court to get access to interview Omar.

HtN: What reasons did they give for denying you access?

PR: Bizarre reasons. They said they didn’t want to increase his notoriety. He was so famous at the time the Prime Minister as talking about him. They didn’t want to upset the working of the prison. Ludicrous reasons really. Finally, and rather unexpectedly, he was granted bail last May so we did the interview the day after he was freed. By then Patrick and Michelle had interviewed everyone else surrounding Omar, his mother, his lawyer, of course, the interrogator, the Delta Force soldiers who shot and thought they’d killed him; they’d never spoken to anyone before. We’d gathered archival material, some re-enactment stuff we’d done, so we were ready – we had to be because within three weeks of the interview with Omar the film had to be ready to broadcast.

HtN: Was the initial broadcast film different from the current version?

PR: Yes, it was forty-five minutes long. So after that we had more time to go back and make the longer theatrical-length film you saw here in Bermuda.

HtN: Was this the first interview Omar had done since his capture?

PR: It’s the only interview he’s done.

HtN: As much as you knew already about him and his case, what did he reveal that surprised or shocked you?

PR: He had thought that he’d thrown that grenade, but then there was doubt cast on that by the soldiers who raided the compound. They said there were two people left live, and Omar was buried under rubble so he probably didn’t throw the grenade. This was a revelation to him. But I think what surprised us all the most was how extraordinarily calm he was about everything. He didn’t harbor any anger against the United States or the US military or the Canadian government or anyone else who’d abused him over the years. He’d decided, as he says in the film, ‘The only thing I can control is my mind and my emotions and I’m not going to let these people destroy me. I’m going to move on.’ It’s extraordinary. I don’t think I’d be so forgiving.

HtN: Going back to what he was accused of doing, was there anyone ever who testified that they saw him throw the grenade?

PR: No. And he has no memory of the incident. He was almost killed, he was shot multiple times – shot in the back when they found him in the rubble – and left for dead. He has no idea what happened, and no one will ever know for sure.

HtN: You mentioned the footage of Omar being interrogated at Guantanamo by CSIS agents. How did you obtain that?

PR: That interview went on for four days and was finally released by order of the Supreme Court of Canada. And then Michelle managed to get footage from a source at The Pentagon, both footage and photos in the compound of Omar working on making the IED, sitting out in the rain alone. He was a fifteen-year-old kid. No one had ever seen that footage before. And all the photos the soldiers took of him when he was barely alive, no one had seen those before either.

HtN: Did anyone you wanted to interview refuse?

PR: There were some people at CSIS and the Canadian foreign affairs ministry who didn’t want to speak. Although we did get a remarkable interview with Geoff O’Brian [spelling unconfirmed] who is the lawyer for CSIS. He spoke quite candidly. He said at one point he thinks the Prime Minister had not read the file on Omar Khadr, yet he was making all these pronouncements about him being an unrepentant terrorist. It became an ideological thing in Canada. They wanted to show they were tough on terrorism and they take it out on this fifteen-year-old kid.

HtN: One of the most striking interviews is with the Guantanamo interrogator who had a complete change of heart.

PR: Damian Corsetti. He speaks very candidly about how brutal he was as an interrogator, his, quote, ‘enhanced interrogation techniques,’ torture in other words. But he says, again very candidly, that Omar was a transformational person. That’s what we hear a lot of people say: meeting Omar Khadr changes them. For Damian it made him realize how crazy what he was doing was. If they were torturing a fifteen-year-old child, what was this all about, what were they doing?

HtN: Omar eventually did get a trial, at which he pled guilty to the murder charge. Was that because he thought it was the only way out of Guantanamo, even though it would mean going to jail in Canada?

PR: Well, he’d already been in jail in Guantanamo for eight years. And it was a horrific thing for his lawyer to have to do tell him to plead guilty to something he didn’t do. But that was the only way to get out of that hellhole. It had worked for others. They’d plead guilty to crimes they didn’t feel they were guilty of, but it got them out of there, got them home. They’d tried for years to get Omar a fair trail and be able to present evidence and argue their case but it was impossible. It was Hobson’s choice, so [his lawyer] advised him to plead guilty. Now, of course, he’s recanted that plea and they are appealing that decision. They may very well win; other people have appealed Guantanamo Bay rulings and have won, so we’ll see.

HtN: Did he get a fair trial, do you think?

PR: It wasn’t conducted under the normal rules of criminal law, according to the judicial system we follow. It was a court set up in Guantanamo Bay just for these ‘unlawful combatants.’ The whole system was set up just for that.

HtN: So it wasn’t under the jurisdiction of any court in the United States?

PR: No. They weren’t allowed to present evidence, and I think it’s widely acknowledged to be outside the rule of law.

HtN: What’s Omar’s status now?

PR: He’s been living in Edmonton with [his lawyer] and his wife Patricia. He’s been going to school, he seems to be doing very well. He wants to work in the medical field in some way, he’d like to be an emergency paramedic. He only has vision in only one eye, so that’s going to limit what he can do in that field.

HtN: What’s the general reaction you’ve had to the film?

PR: The film premiered at the Toronto Film Festival last year to standing ovations. We’ve had excellent reviews, we won the audience choice award at the Calgary Film Festival, where Omar appeared and did a Q&A. It’s doing the rounds of other festivals. It’s been very well received. We get a lot of emails, especially Michelle, and most of them are very positive. I think it is changing people’s minds about Omar Khadr, about who he is and what happened to him. The new liberal government in Canada, elected last fall, have decided not to appeal the bail. The previous government said they were going to appeal it. So he’s now out on bail and he’s not going back to jail.

HtN: What’s his status regarding the United States?

PR: I believe he’s on the no-fly list, which means he can’t travel through or even over the United States. He can travel in Canada, he recently traveled to see his grandparents in Toronto.

HtN: What do you think the wider issues of Omar’s story are?

PR: The wider issue is Guantanamo Bay and the horror that it has been for so many years, and still is. It shouldn’t exist, should never have existed. It’ll be a dark stain on American democracy and the rule of law forever.

– Simon Braund