The Portuguese filmmaker Miguel Gomes first drew attention in the United States with his film Our Beloved Month Of August, a brilliant piece of docu-fiction that examined life in Portugal, breaking apart traditions and deeply held cultural beliefs with wry humor, exquisite storytelling and a transgressive approach to cinematic form. His third feature film, Tabu, takes his approach into a new dimension, pulling forward and backward in time to explore the history—and the cinematic legacy—of the Portuguese colonial experience in lusophone Africa. The film won the FIPRESCI Prize and the Alfred Bauer Award during its World premiere run the 2012 Berlin International Film Festival before taking the festival circuit by storm.

The Portuguese filmmaker Miguel Gomes first drew attention in the United States with his film Our Beloved Month Of August, a brilliant piece of docu-fiction that examined life in Portugal, breaking apart traditions and deeply held cultural beliefs with wry humor, exquisite storytelling and a transgressive approach to cinematic form. His third feature film, Tabu, takes his approach into a new dimension, pulling forward and backward in time to explore the history—and the cinematic legacy—of the Portuguese colonial experience in lusophone Africa. The film won the FIPRESCI Prize and the Alfred Bauer Award during its World premiere run the 2012 Berlin International Film Festival before taking the festival circuit by storm.

Hammer To Nail saw the film at the 2012 Toronto International Film Festival before sitting down with Miguel Gomes in October to discuss his new film during the director’s visit to The New York Film Festival. Distributed by Adopt Films, Tabu opens today—Friday, December 26, 2012, at Film Forum in New York City and will spend the winter rolling out around the country.

Hammer To Nail: I want to begin by discussing lusophone African cinema, in particular the post-colonial revolutionary cinema of the 1960s and ’70s. Those films were addressing, it seems, many of the issues that your film Tabu takes on in its own, unique way.

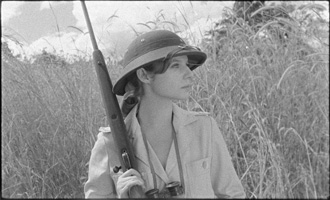

Miguel Gomes: To be honest, I think the film is more close to the mythology created by colonialism and cinema. The Africa invented by Hollywood for instance; that goes from Tarzan to something like Out Of Africa, to films like Mogambo and Hatari—closer to the classic American cinema than the revolutionary cinema of Africa itself, which, in the case of Angola and Mozambique, I just don’t think they had enough of a cinematic tradition at the important moment. After their independence in 1975, the former Portuguese colonies, civil wars started and there was not an opportunity to make these films. From the perspective of Tabu, there was an idea I had from the start; in the second part, there are these guys, white people, who act as if they are in a film. They are enjoying themselves and are completely unaware, socially and politically, what is happening around them. By the end of the film, they find themselves astonished that there are people in Africa who want to be independent from them.

So, there was always this perspective of making a two-part film; in the first part, the character of Pilar seems completely aware of what happened, very concerned. I don’t know if all the prayers and protestations she does will help or put the world in a better state, but she’s aware of this and she is a character who wants to deal with guilt. I think there is vague guilt that exists in the first part of the film, not only the guilt of the character of Aurora, but a kind of disseminated guilt. In the second part, you see the origins, these white people pretending to be in a Hollywood film, their love affairs and pet crocodiles and enjoying one another. This imaginary Africa comes from the white, American mainstream cinema that invented its own exotic Africa.

H2N: There is also the European tradition—Jean Rouche, others—who address this head-on in a different way than Tabu. This idea of ethnography which, in your film, seems more like subtext. The characters imagine themselves as Hollywood heroes, but the world around them operates in a completely other way.

MG: Yes, I remember, for instance, the crew asking me: “OK, there are these kids here wearing Obama T-shirts. We have to get them out of the shots.” And I said, “Hell no.” We are making a fiction, the actress with the stylish hair from the 1960s and the fake moustache, that’s the fiction, but it is only interesting if this fiction is taking place here among these modern kids. I would never try to take away the things they were doing, even if it was completely anachronistic. I think that film is for people to believe, but it should not impose its believability to the viewer. By now, I hope that everyone knows that the cinema is fake, and so the ability of believing, going into a film and believing it, I don’t think that it has a relation with the fact that you tried to re-create everything with perfect, historical accuracy. I don’t think the film is “more true” if we only have 1960s furniture.

MG: Yes, I remember, for instance, the crew asking me: “OK, there are these kids here wearing Obama T-shirts. We have to get them out of the shots.” And I said, “Hell no.” We are making a fiction, the actress with the stylish hair from the 1960s and the fake moustache, that’s the fiction, but it is only interesting if this fiction is taking place here among these modern kids. I would never try to take away the things they were doing, even if it was completely anachronistic. I think that film is for people to believe, but it should not impose its believability to the viewer. By now, I hope that everyone knows that the cinema is fake, and so the ability of believing, going into a film and believing it, I don’t think that it has a relation with the fact that you tried to re-create everything with perfect, historical accuracy. I don’t think the film is “more true” if we only have 1960s furniture.

I think that Jean Rouche, for example, was always playful. Mixing up and messing with ethnography, that’s interesting for me. For example, Murnau’s Tabu was also a very strange film. It looks like the natives are Polynesian, it invents a place for them to be, but the film imposes a whole fiction on this set-up. I feel close to that idea, but at the same time, the material reality is vital for me; if I am going to make a film about Africa, I can’t set it up somewhere else, I have to be there. I need the real thing with African trees and African people and then mix that with a fantasy that we invent. I think that corresponds with Murnau’s Tabu, which was the last one he made (he died afterward); it’s like a utopian cinema. It is a film that makes itself available to things that you would never otherwise see in a Holiday film made at this moment—it’s open to the world—but at the same time it is completely under Murnau’s strict control. This balance between availability to the world and the belief in manipulating the tools of cinema seems like an unexpected marriage, but it is a very profitable one.

H2N: When you’re constructing that fantasy, knowing you’re going to impose it on top of the historical tradition of the Portuguese colonial experience as well as these pre-existing modern conditions, do you feel a political responsibility? How do you weave that into the process?

MG: In Portugal, this issue of colonialism and everything that is attached to it, it was sensitive. After 1975, many people returned from the colonies to Portugal, there were many people alive who fought in the war and all I can say is it was a sensitive issue. There were many debates in the 1970s and it was alive at that moment as a very specific question for the people. Now, what happened is that fiction in Portugal—literature, but also cinema—tried to have a very didactic approach to the topic, wagging a finger at the viewer as if he was a child. I don’t think we have to do that. For me, I take for granted that by now, people understand that colonialism was not a good system. I hope I don’t have to follow that approach.

MG: In Portugal, this issue of colonialism and everything that is attached to it, it was sensitive. After 1975, many people returned from the colonies to Portugal, there were many people alive who fought in the war and all I can say is it was a sensitive issue. There were many debates in the 1970s and it was alive at that moment as a very specific question for the people. Now, what happened is that fiction in Portugal—literature, but also cinema—tried to have a very didactic approach to the topic, wagging a finger at the viewer as if he was a child. I don’t think we have to do that. For me, I take for granted that by now, people understand that colonialism was not a good system. I hope I don’t have to follow that approach.

Coming to Mozambique, which is one of the poorest countries in the world, and doing a fiction—that’s why I told you that you must show the fiction aspects of the film as a lie. You have to show that this is a fantasy and does not belong to the real world. There are two realities, the fantasy world of the fiction—cinema—mixed with the material reality of Mozambique. I think you must show the fiction as a lie even if afterward it is harder for people to believe the unbelievable things in the film. You have a clash; the fiction must be unreal, the reality must continue to be real. For this clash to be productive and have meaning, you have to be honest and not move things outside of the shot, you must show both.

For instance, in the script, we had the first half scripted but the parts in Africa were made up there. The general storyline came from the script, but we didn’t have enough money to shoot what was in there, so we just improvised. In the original screenplay, there were more scenes about the rise of the independence movement. There is that scene in the church where you see the first sign of the military, of the war to come. There is a single shot of the “leader” and the people looking at him. This was for me a way to put the guy with the big mustache who looked the type—that was the lie—and then there were guys there from the village who were there for mass at the church, so I just filmed them sitting there, in their own clothes, and this was real. For me this clash, in this case says “the war that you’re starting is already lost.” The people are real, the warlord is fake, the war is lost already, before it has started.

H2N: We’re running out of time, but I wanted to address the issue of memory, of cinematic memory. This film is primarily told from the point of view of someone’s memories, which is untrustworthy. Movies have always had this relationship to memory; can you talk about how this worked for you in structuring this story?

MG: Before we meet the character who tells us the first story, we hear from someone who tells us he’s a little bit crazy. And then, he goes to tell the story to Santa and Pilar. So, is this the story we’re seeing? Is it a flashback? Is he talking to them or talking to himself? He speaks in a very literary way, so it’s not realistic speech for someone just telling a verbal story. So, I don’t know. I don’t have an answer. Is the screen showing his story or is it showing what the listener is imagining? We know one is always going to the cinema and one is reading Robinson Crusoe, so which is it?

MG: Before we meet the character who tells us the first story, we hear from someone who tells us he’s a little bit crazy. And then, he goes to tell the story to Santa and Pilar. So, is this the story we’re seeing? Is it a flashback? Is he talking to them or talking to himself? He speaks in a very literary way, so it’s not realistic speech for someone just telling a verbal story. So, I don’t know. I don’t have an answer. Is the screen showing his story or is it showing what the listener is imagining? We know one is always going to the cinema and one is reading Robinson Crusoe, so which is it?

But yes, I guess the film deals with memory this way and deals with keeping things that will disappear, people that, like Aurora, are going to die, recollections of the society that doesn’t exist anymore, like colonial society in Africa, and even from the cinema that has disappeared, like silent films or classic American films. Cinema has the ability to have this and re-invent this while imposing its own fiction. It fabricates fiction because there is this desire. The first part of the film is ordinary people living ordinary lives, and all of them share a desire for fiction. We need that. The second part appears to be a flashback, it could be a dream, it could be the women hearing the story who are making up these images, it could be the crazy storyteller, he could be saying the truth. All of these things are trying to fulfill the desire of the characters and to share that with the viewers.

H2N: Where do you see yourself in all of this as a director? You’re building all of this to create a story and tell it to us. Ultimately, this is your responsibility. How do you see this for yourself?

MG: I’m providing a space for the viewer. For instance, I think I have a problem with 80% of the films that are being made today. That means mainstream cinema but also art house films. In most cases, the point of view of the director is completely imposed. I don’t have the choice as a viewer to decide how to feel or how to think because it is constantly being imposed on me. So, my job as a director is to show different things. I think the film is completely ironic and at the same time, and this is a contradiction, completely available to the emotions of the characters. I guess that could be seen as a contradiction but I don’t think so; I think that’s what provides space for the viewer to relate; you have the opposite poles and you can move closer to one, then move closer to the other, always shifting. I am providing the viewer this space to bring his own sense of humor, his knowledge, his own interests, whether he cares or not, to move inside the film.

MG: I’m providing a space for the viewer. For instance, I think I have a problem with 80% of the films that are being made today. That means mainstream cinema but also art house films. In most cases, the point of view of the director is completely imposed. I don’t have the choice as a viewer to decide how to feel or how to think because it is constantly being imposed on me. So, my job as a director is to show different things. I think the film is completely ironic and at the same time, and this is a contradiction, completely available to the emotions of the characters. I guess that could be seen as a contradiction but I don’t think so; I think that’s what provides space for the viewer to relate; you have the opposite poles and you can move closer to one, then move closer to the other, always shifting. I am providing the viewer this space to bring his own sense of humor, his knowledge, his own interests, whether he cares or not, to move inside the film.

H2N: Same thing with the silence within the film… there is a lot of ambient sound, not a lot of dialogue…

MG: Yeah, I had the desire to build the fantasy in its own way, not as an homage—I don’t think cinema needs homages—but I had this idea of someone recalling an ancient story and time has erased the precise words the characters said to each other. I brought it from that to this silent film which is, you know, a form that has disappeared. If the characters in the first part are longing for anything, I think it is their youth. I think that the cinema also misses its youth, that during this more than 100 years of cinema, the viewer has lost some of the innocence and availability they would have had when the cinema was new.

— Tom Hall

Pingback: TABU – Hammer to Nail