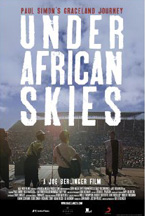

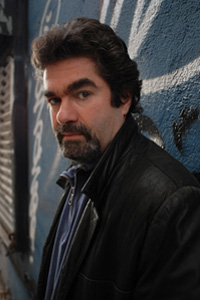

A Conversation With Joe Berlinger (UNDER AFRICAN SKIES)

(Under African Skies world premiered at the 2012 Sundance Film Festival and will begin its theatrical run at the IFC Center in Manhattan on May 11th and other cities around the United States. A box set of the album Graceland and the movie will be released on June 5th.)

(Under African Skies world premiered at the 2012 Sundance Film Festival and will begin its theatrical run at the IFC Center in Manhattan on May 11th and other cities around the United States. A box set of the album Graceland and the movie will be released on June 5th.)

Rest assured, Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky’s relationship is okay. Their partnership does not mirror that of Simon & Garfunkel, one filled with years of friction or the constant need to create distance. Nor do their reunions have the whiff of financial windfall.

Berlinger and Sinofsky have, to date, made five amazing documentaries, including: Brother’s Keeper (1992); Metallica: Some Kind of Monster (2004): and the Paradise Lost Trilogy, the latter segment of which premiered at last year’s Toronto International Film Festival, just days after the release of the West Memphis 3.

No, Joe and Bruce’s relationship seems to have a much stronger fiber than that. It’s just that occasionally one must also go it alone and create personal works of art as well. Without those bold moves, after all, the seminal Paul Simon album Graceland would never had been made. (Can you imagine Artie singing the Ladyship Black Mambazo parts? Yikes!) After Joe Berlinger was finally able to settle all his legal problems arising from his last solo directorial project, Crude, he wanted to focus on something more positive and upbeat. When he was approached by Simon about the project, which follows the iconic singer-songwriter back to South Africa for a 25th anniversary reunion concert, the filmmaker could not refuse.

Joe and I spoke recently just hours before he was making a whirlwind trip around most of the world.

Joe Berlinger: Two seconds. I just gotta heat up my coffee.

Joe Berlinger: Two seconds. I just gotta heat up my coffee.

Hammer to Nail: I understand.

JB: I’m going on this massive seven-week trip around the world for another production. I’m going to Tierra del Fuego, then to Morocco, then to China.

H2N: If you need someone to make the coffee…

JB: Come on down!

H2N: Can you give us some of the back story on how you came to be involved in this project? Were you approached?

JB: This did come to me but there’s a slightly interesting story behind it. Early last year Sony realized it’s the 25th anniversary of Graceland. They talked to Paul Simon and his management, “Should we do something? Let’s [release] a box set, let’s do a movie, a documentary maybe.” I had done an episode of Iconoclasts, you know, that TV series.

H2N: That’s the one on the Sundance Channel.

JB: Yes, where we take two well known people from different fields and throw them together for a couple of days and see what happens.

H2N: Right.

JB: I did an episode with Paul Simon and Lorne Michaels. My name came up I guess because I was the last documentary maker he had worked with. [JB laughs] And we had fun doing that show. My name was bandied as someone who could do the film and so I was approached.The interesting story to me about this is that on one hand I was very excited about being approached and also extremely, you know, I had a lot of trepidation about it. The excitement part was I remember the record coming out. I was 25 years old. I’m 50 now. And of course like anybody there are many Paul Simon songs that resonate with me but I can’t say that I was this massive fan. But Graceland really struck a chord with me. You know there are certain records that you listen to over and over again, never tire, and always discover something new. Other records, after the fourth hearing you just don’t want to hear again. Graceland, for me, was one of those records you just play over and over and over again—and I have for 25 years! It’s like a record that’s kind of my go-to album when I’m down. To me that’s what defines a classic album, an album that you just never tire. And again, I liked Paul Simon prior to that record and certain songs, you know, I associate with a lot of positive memories of growing up; but it’s not like Simon & Garfunkel or Paul Simon was at the top of my list of favorite artists prior to Graceland. But Graceland was just an album that spoke to me very deeply.

JB: I did an episode with Paul Simon and Lorne Michaels. My name came up I guess because I was the last documentary maker he had worked with. [JB laughs] And we had fun doing that show. My name was bandied as someone who could do the film and so I was approached.The interesting story to me about this is that on one hand I was very excited about being approached and also extremely, you know, I had a lot of trepidation about it. The excitement part was I remember the record coming out. I was 25 years old. I’m 50 now. And of course like anybody there are many Paul Simon songs that resonate with me but I can’t say that I was this massive fan. But Graceland really struck a chord with me. You know there are certain records that you listen to over and over again, never tire, and always discover something new. Other records, after the fourth hearing you just don’t want to hear again. Graceland, for me, was one of those records you just play over and over and over again—and I have for 25 years! It’s like a record that’s kind of my go-to album when I’m down. To me that’s what defines a classic album, an album that you just never tire. And again, I liked Paul Simon prior to that record and certain songs, you know, I associate with a lot of positive memories of growing up; but it’s not like Simon & Garfunkel or Paul Simon was at the top of my list of favorite artists prior to Graceland. But Graceland was just an album that spoke to me very deeply.

H2N: What were your memories from that time?

JB: As you can guess from my filmography, I was a very politically aware 25-year-old and I was vehemently anti-apartheid. I remember Paul being criticized for having recorded in South Africa. I remember kind of scratching my head and not really understanding that criticism. The cultural boycott [the African National Congress’s cultural boycott was set up to discourage international artists from performing in South Africa during the apartheid years], which I thought was a very important thing, was about those artists coming to South Africa and performing for white segregated audiences and thereby legitimizing the apartheid regime. That I understood. But it was very unclear to me, why recording with black South Africans, the voice of the oppressed, was an act of transgression against the cultural boycott. Also, I could never understand why South African musicians were not allowed to tour the world. There was a certain rigidity to the boycott that I never understood. Because what Paul was doing with this record—and I don’t think he consciously went to South Africa to… I think he was just following his muse—but what it morphed into—and very consciously on his part with the subsequent tour— is that he was basically exporting the very culture that the apartheid regime was trying to crush; that black South African musical heritage.

So for Paul to create this vehicle for that culture to be exported and celebrated, I never understood why that was being criticized. I remember my feeling that that well before I even had an inkling that I would ever make a film about it. This was even before I was a filmmaker, in fact.

So, when I got the phone call to go explore this, I was enthusiastic about the idea but also apprehensive. Because, you know, this project was being generated by the record label. Would they really want to get into this controversy? Would Paul want to get back into this controversy? What I didn’t want to do was a Paul Simon puff piece. Without naming names, there have been quite a few films made of late that are meant to be included in box sets and they don’t go very deep.

H2N: The type of film that doesn’t necessarily stand on its own from an artistic standpoint?

JB: Yeah, I didn’t want to make a film that is just glorifying the artist.

H2N: Basically you weren’t interested in making an ad.

JB: Right. I wanted to make a real film basically. Even though I was kind of already on his side in regard to the cultural boycott issues, I wanted to make a film that would explore both sides of the issue. So I met with Paul at his office in March of 2011 and had a deep conversation about what kind of film should be made and if I was, in fact, the right person to do it. To my delight, he shared my vision that we should be going into the controversy and that it shouldn’t be a puff piece.

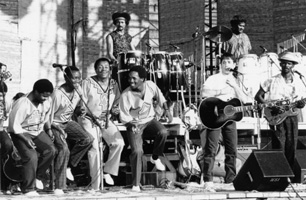

I think the political story is a story you can’t avoid. The cultural imperialism question of appropriating black music—which is the other criticism that was directed at Paul—is a question you can’t avoid. But to me the most important part of the film, and I think he would agree with me on this as well, is a dissection of the musical story. I think Graceland, and what people are responding to, is really quite an achievement in musical history. It was a breakthrough for him as an artist even though he dabbled with that methodology in the past. A song like “Mother and Child Reunion” is an example of going to the source, assembling the rhythms and the instrumental tracks prior to actually writing a song on top of it. So he dabbled with this style in the past. Graceland was the grandest expression of that methodology, and in a pre-Pro Tools era how that record was made: again going to the source, being inspired by certain sounds, changing certain sounds, creating other sounds, creating those rhythm tracks, then hauling all that stuff back to New York and then writing songs on top of it! That was revolutionary for how songs were generally written by him and by other artists. So I really wanted this film to be a dissection of that process, to understand how that music was made, and to understand the brilliance of his collaborators because these were some of the most incredible musicians.

I think the political story is a story you can’t avoid. The cultural imperialism question of appropriating black music—which is the other criticism that was directed at Paul—is a question you can’t avoid. But to me the most important part of the film, and I think he would agree with me on this as well, is a dissection of the musical story. I think Graceland, and what people are responding to, is really quite an achievement in musical history. It was a breakthrough for him as an artist even though he dabbled with that methodology in the past. A song like “Mother and Child Reunion” is an example of going to the source, assembling the rhythms and the instrumental tracks prior to actually writing a song on top of it. So he dabbled with this style in the past. Graceland was the grandest expression of that methodology, and in a pre-Pro Tools era how that record was made: again going to the source, being inspired by certain sounds, changing certain sounds, creating other sounds, creating those rhythm tracks, then hauling all that stuff back to New York and then writing songs on top of it! That was revolutionary for how songs were generally written by him and by other artists. So I really wanted this film to be a dissection of that process, to understand how that music was made, and to understand the brilliance of his collaborators because these were some of the most incredible musicians.

H2N: As evidenced in your film.

JB: So Simon was right there with that idea. I felt that I could make a film that would stand on its own even though it would be included in a box set. And you know, after the Metallica film—obviously the Metallica film was hugely successful—I was approached half a dozen times by various bands to make a concert film or a road film. I’m generally not a fan of just watching music on the big screen. I believe in listening to music and watching films that have stories. So, to me a music film has to have something else besides just music. There needs to be a cinematic story. The Metallica film I think was strong because in addition to getting the music, to understanding the music, experiencing the music, there’s a much deeper story being told: the vicissitudes of fame and fortune.

H2N: Right. There’ve been other music related projects, correct?

JB: I made a film about gospel music, that one was kind of under the radar. It was a film I made for television that I really loved called How Sweet the Sound. It was about a gospel competition. And it worked because it was just an incredible story. Real church gospel choirs competing for the best gospel choir.

H2N: Yes.

JB: And that’s a story. So for this film, the idea of Paul Simon going back to South Africa and reuniting with these musicians to play those songs again after 25 years, to use that as a springboard to dissect the music. And, just as importantly, from the cinematic standpoint Paul’s journey is both a musical journey and a journey to understand the criticism.

H2N: And I found that what was remarkable was that here it is, 25 years later, and that conversation with Dali Tambo [son of former ANC leader Oliver Tambo], is the backdrop of the film in a way. Their conversation throughout the film, and then at the end in Simon is sort of exonerated, and you could see the joy that he feels. He just seems like he had this burden lifted off of him in a way. I’m wondering how that part of it came about.

JB: I don’t think Simon felt guilt at all, I think he felt misunderstood.

H2N: It bothered him that he was misunderstood.

JB:I think he feels that he did nothing wrong but stumbled into a political hornet’s nest and was stung.

H2N: So you don’t think he was seeking exoneration on some level from Tambo?

JB: I don’t think it was exoneration; I think he wanted to get his view off his chest and have his say. And I think it was a great relief and catharsis for him, but I don’t think he was taking the position that he did something wrong or that he was guilty. I think it bothered him that he and his motives were misunderstood by some. And the opportunity to exchange his views with his nemesis on this issue was very cathartic. I think for Dali Tambo too. It was a very healing conversation. I don’t think either one really changed their viewpoint, just that they had a deeper understanding of one other.

JB: I don’t think it was exoneration; I think he wanted to get his view off his chest and have his say. And I think it was a great relief and catharsis for him, but I don’t think he was taking the position that he did something wrong or that he was guilty. I think it bothered him that he and his motives were misunderstood by some. And the opportunity to exchange his views with his nemesis on this issue was very cathartic. I think for Dali Tambo too. It was a very healing conversation. I don’t think either one really changed their viewpoint, just that they had a deeper understanding of one other.

H2N: They were able to find a middle ground.

JB: They were able to understand each other’s position without really moving away from the views they had. It’s like having a human understanding of your adversary, but nothing past that. I think it was a big relief, the movie is obviously structured around that confrontation and I think that’s what elevates the film to the point of being a film as opposed to the types of films that I had passed on which was just, “Let’s go record people playing music.” And it happened quite spontaneously and I think that’s why it works. We were in the country for ten days, Dali Tambo was on the list of people I wanted to interview going into the trip. We hadn’t even heard back from him. Some of the interviews, which were set up with the people who had agreed to do it, ended up not making it into the film. But from Dali we hadn’t even gotten a response back. Hugh Masekela, who is tight with a lot of people at the ANC, was very instrumental in making this happen.

H2N: Instrumental, eh. No pun intended?

JB: Right! So on the third to last day of our trip, the last day being that anniversary concert, Dali had agreed to do a single interview at his house. He was not what I had expected. I don’t know what I expected, but I found him to be a very charming, very engaging, interesting guy; sympathetic. He’s about my age, and I think we kind of clicked. So while I was interviewing him the thought popped into my head: You know what? It would be a lot more interesting to have Paul sit down, have them talk together instead of me interviewing him. I suggested that, and I think he was taken aback a little bit or surprised about the suggestion. He said, “Let me think about it.” I spoke to Paul that evening at our hotel and Paul actually immediately embraced the idea, and agreed to do it. The only day we could do it would be the next morning because Paul had to go to rehearsal and time was ticking, so I called Dali and he finally agreed to do it. So we ran back the next morning. Nobody really had any time to prepare. It just sort of happened magically at the end where they hugged and I just knew we had a moment and that that was going to end up being the present structure of the film; it would be the springboard of the entire story.

In fact, a funny thing happened: I had actually scouted out and picked a different room to shoot this in. I was going to have them at a table so that it would be more comfortable, more easy to shoot because two people plopped on a couch is not the easiest thing to do. So I had my gaffer go in advance and hang a light before we actually arrived because the lighting in the room was a little dark, and they embraced at the doorway and on their own they walked to the couch, plopped down and immediately started talking. My cameraman, Bob Richman, who has been working with me for 20 years, gave me a look which I know means, “Are you sure you don’t want to stop and move over to the place we talked about shooting the scene?” My instinct was no, this is happening so spontaneously and it’s so much richer. I didn’t have to ask a question or prompt it; it just started happening without any direction on my part. I just felt that if I stopped this and reset it, everyone would become self-conscious and aware that we were shooting the scene. I’d rather have something that doesn’t look the best but has this pure content. So we just kept rolling for literally two hours. Very few words were given by me; normally I would say, “Sit here, we’re going to start, blah blah blah.” But here there was no directing, they just walked in, got into it. Two hours later, they hugged. It was an amazing moment. It makes the film.

— Adam Schartoff

Pingback: HOME VIDEO PICKS – Hammer to Nail