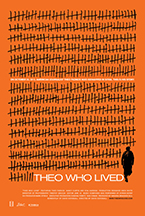

A Conversation with David Schisgall (THEO WHO LIVED)

I recently spoke by phone with filmmaker David Schisgall, who directed the just-released documentary Theo Who Lived (which I also reviewed). The film tells the story of the kidnapping, captivity and eventual release of conflict reporter Peter Theo Padnos, held in Syria by an Al Qaeda affiliate for almost two years, as seen through the eyes of Padnos, himself. It’s a powerful meditation on how to survive – and evolve beyond – the seemingly never-ending cycle of violence in our world. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for clarity.

I recently spoke by phone with filmmaker David Schisgall, who directed the just-released documentary Theo Who Lived (which I also reviewed). The film tells the story of the kidnapping, captivity and eventual release of conflict reporter Peter Theo Padnos, held in Syria by an Al Qaeda affiliate for almost two years, as seen through the eyes of Padnos, himself. It’s a powerful meditation on how to survive – and evolve beyond – the seemingly never-ending cycle of violence in our world. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for clarity.

Hammer to Nail: I know from your press notes that you came to this story through your wife. Can you describe her relationship to Theo and how you became interested in filming him?

David Schisgall: Well, I’d never met Theo before I pushed to make this film, but my wife had known him when he was between the ages of 7 and 13, when he was her brother’s friend. And so, when he went missing, I heard about it before it was public, and having done work like that in the past, I was really affected by the story, and when he was released, I kind of got the sense from what he was interested in doing that we might be a good fit. And so I reached out to him.

HtN: What made you decide to tell Theo’s story by traveling with him back to where he was captured?

DS: Well, we didn’t go all the way back to where he was captured. Everything that takes place before he goes across the Syrian border takes place where it happened in southern Turkey. And everything from when he’s picked up on the Golan Heights takes place where it happened, in Israel and back to the States. But Syria is far too dangerous to travel into, and so we found places, either in southern Turkey or in Israel, that felt like the places he was captured. And then for some of the bigger sequences, we built sets, in Brooklyn, that looked like where he’d been captured. So we didn’t actually go back in to where he was captured. We went back to where he was taken, but not where he was held.

So Theo originally had this idea – he’d been talking to my brother-in-law, whom he’s very close to – of wanting to do a kind of Swimming to Cambodia kind of thing. I tried to imagine how you could make that less static, like not on stage, someone telling a story in an interesting series of places, and I thought, “Well, what if we told each of the stories in a place that was where it happened or a place that felt like, or looked like, where it happened?” And it seemed to work out well. Later, once the film came out, people reminded me that that’s just what Werner Herzog did in Little Dieter Needs to Fly, a movie I’ve seen and adore, but I guess I blocked out…it never occurred to me that that was his style in that film.

HtN: It’s funny that you say that, because one of my questions was going to be about Little Dieter Needs to Fly…

DS: I love that movie, and I love Werner’s work, so I’m thrilled when people say it reminds them of Little Dieter Needs to Fly! Some people also say that it reminds them of Grizzly Man, which I also take as a compliment.

HtN: Was anyone during the filming process, including Theo, concerned – given that you were reenacting scenes where he had been traumatized – about any sort of re-traumatization?

DS: Yes. Everyone involved was concerned about that. You know, I had done films with traumatized people before: I did a film called Very Young Girls, about teenage girls that have been brutally sexually exploited. I even did some work with some hostages who had been held in Colombia during the war there. So I came with some experience of dealing with people who’ve had these kind of things, and Theo came back wanting to tell his story. He wanted to tell it to whomever would listen, and that was his way of processing it. When we had this idea, he was really into it; he wanted to go back, because Theo loves those areas, and he liked the idea. There was one…it’s not in the film…the first night we got into Antakya [in southern Turkey], Theo had a little – very minor – flashback. That was the worst of it. Because he handled it really well.

You know, Americans have this idea that there are only two narratives about people who have been captured by our enemies: one is that they’re a ticking time bomb, waiting to explode; and the other is that they should be President of the United States, like John McCain. But there all kinds of different outcomes in the middle, and people deal with problems in so many different ways that I felt that I and the people who were close to Theo, and around Theo, and concerned about Theo, thought that this was a really good thing for him. It was a way that he wanted and it seemed like a really healthy way of him processing what had happened. You know, tell it again, which is a kind of therapy, or it can be therapeutic, if done in the right way. And I don’t think that the work, overall, hurt him. I think it helped him, and I think everyone involved in his case feels that way, too.

HtN: Related to that question, I love Theo’s sense of humor. For example, when he says, deadpan, “It’s a lot of fun, Jihad. Very underrated, in the West.” He seems pretty upbeat, actually, throughout the film. Were there any moments, other than that opening night which you mentioned, when he faltered, or grew melancholy, in the filming?

DS: Most of those moments are in the film. When he’s on the couch with [his cousin] Viva, he’s very emotional. When he’s talking about his attempted suicide, he’s pretty emotional. In that scene where he’s reenacting the beating, there was a lot of anger coming out. So I think a lot of that is in the film, actually.

HtN: OK. So I really liked how much of the film is shot. You hired two veteran war videographers, Tim Grucza and Rachel Beth Anderson, to shoot the film. Had you worked with them before? What did they bring to the movie?

DS: I hadn’t worked with either of them before. The thing that really appealed to me about the two of them, even before I met them, was that they had done the same kind of work, and taken the same kind of risks, that Theo had, and that I had. I knew immediately that they would have the same feeling about that I did, you know, “There but for the grace of God go I.” That was what really me sold me on the two of them, all of us having that similar touchstone, and also being people who were interested in the Middle East, and liked being in those countries. I wanted it to be a film not about war journalism – freelance war journalism – but by freelance war journalists. And they were wonderful, both of them, Tim and Rachel, when we were humping around the developing world, and they were fantastic when we had lights and assistants.

HtN: Final question. Has making this film, and living Theo’s experiences vicariously, affected your own decision to film abroad in the future?

DS: No. I mean, I’ll go where the story takes me, but I gave up that kind of, you know, “go by yourself into a war zone” work some time ago. I did come away with a sense, though, and I think this is something I hear more and more…we did this interview with Nicolas Kristof, and he asked me about this…which is that there are so many good, talented people in these countries who understand what’s going on at a level so far and above what we could ever hope for that the emphasis should be on local reporters, and enabling them to do the work that they can do. I think that work would be better! (laughs) And also less dangerous. That’s my takeaway. It’s very important for us to promote and help local newsgatherers, because they’re the ones who should be doing the job and they’re the ones who are doing it best.

HtN: Thank you. And thanks for making the film!

DS: Well thanks for watching, and thanks for writing about it.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)