A Conversation With Bill Ross (CONTEMPORARY COLOR)

(The 2016 Tribeca Film Festival kicked off April 13 and runs through April 24. Hammer to Nail is representing so keep an eye on the site for frequent reviews, interviews and other excitement!)

(The 2016 Tribeca Film Festival kicked off April 13 and runs through April 24. Hammer to Nail is representing so keep an eye on the site for frequent reviews, interviews and other excitement!)

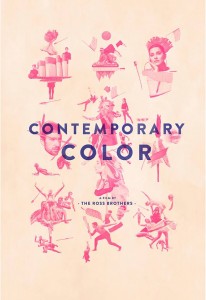

With the premiere of the David Byrne-helmed color guard concert film Contemporary Color this week at TriBeCa Film Festival, Bill and Turner Ross shut the door on their lo-fidelity trilogy of documentaries that came before. Their previous films, including the most recent Western, were marked by a style best described by Agnès Sire: “No attempt is made to reassure the spectator. There are no captions…just a flow of images that must exist on their own terms, fragments of the ordinary.” Sire was describing the work of photographer William Eggleston, but the definition is perfectly applicable to the Ross Brothers’ style, each film a thoughtful snapshot of its subject presented to the audience as an encapsulation of a moment, consciously avoiding the clarity of high-definition images and the politicization of the outside world.

Not so with Contemporary Color. The film explodes with beauty in a Busby-Berkley-meets-The-Muppet-Show glitter bomb of joy and friendship that culminates in a brief glance to the politics of the outside world. Just before David Byrne (here characterized as a sweater-wearing Mr. Rogers who cheers on teams of color guard with seemingly uncontrollable fits of exuberant singing) takes the stage, we see a brief shot of a television playing in the backstage green room: a news report shows the White House lit in a rainbow. The Supreme Court has legalized gay marriage. In this small moment the film ascends into a document of America’s changing political landscape. How beautiful that Contemporary’s titular color might actually be a spectrum: the rainbow.

The trajectory from their previous film, Western, to Contemporary Color on its surface seems like a huge leap. The brothers shot the former over the course of a year with a pair of standard-definition DVX-100 cameras while the latter employs a team of camerapersons to catalogue two massive, single-night performances in 4K resolution. But a look back on Western with Bill Ross illuminates the path.

Even as the dealings of Mexican drug cartels threaten the business of cattle rancher Martin Wall, Western resists focusing on the larger, global scope of the problem and instead documents how the existence of cartels feels in every day life: as a leering, invisible threat, sensed but not seen. Thunder rolls over the border towns of Eagle Pass, Texas and Piedras, Mexico in a Shakespearian show of force, but the film punctuates itself with musical interludes, predicting and informing the musical structure of Contemporary Color. As the landscape of Western becomes increasingly threatening to its inhabitants, the Ross Brothers insist on focusing their camera on the porch-front, beer-in-hand conversations that take place amidst the fear. You can almost hear Contemporary Color’s Zola Jesus singing from the future, “I don’t want to see the world, I only want to see you.” We sat down with Bill Ross to dig deeper into Western as well as the Brothers’ latest, Contemporary Color.

HAMMER TO NAIL: Western is set on Rio Grande but the structure was much more like Rio Bravo. I felt like I was watching a musical. While you’re shooting are you thinking about structure at all? Or does that completely come in the edit?

Bill Ross: No, no, no. Everything is very, very structured going in, and then, of course, that all falls apart on the first day. There is the preconceived movie going into it, but with the knowledge that we are just along for the ride. We don’t try to force anything in to this pre-assumed idea. But because of my brother, we like to be prepared.

H2N: What was the preconceived idea of Western?

BR: Well, funny backstory – give me two seconds I’m going to go get a beer real quick.

H2N: Do it.

BR: We just had our second annual Always for Pleasure festival. I think we’re developing the greatest party weekend that we could imagine. I bring it up because we have so much leftover beer. This year we played A Poem is a Naked Person, the Les Blank film. It is easily in his top five and it is just a bat-shit film. You know the backstory on that?

H2N: I don’t.

BR: All Leon Russell’s friends were getting movies made about them and he was like, “Where’s my movie?” So, he just called AFI himself and was like, “Hey, who makes documentaries?” And there’s this new cat Les Blank. He had just shot Dry Wood and Hot Pepper, I believe. And Les said, “Yeah I’ll come out if I can stay at your compound and edit these two films while we’re shooting.” So, he cut those two films in Oklahoma. Les stayed there for two years and mostly shot [Leon’s] neighbors and the landscape. That’s why the film didn’t come out, because Leon probably saw it was like, “What is this? You’re interviewing my neighbor.”

Anyway, 45365 shows at South By Southwest. The first Q&A has just been conducted. I am nervous as all hell and I rush out to have a cigarette to get away from how overwhelmingly crazy that was. And as I’m on my way out the door this famous documentarian grabs me and he bear hugs me. He says, “My god! This is the best thing ever! We need to work together!” He’s like, “I want to do a TV series in Detroit.” So, Turner and I had all these films that we wanted to make but, sure, we’ll go do this and make a lot of money to fund our other shit. So, we took all these meetings with all these different channels and finally we meet AMC and AMC was pretty pumped about it. They heard the pitch and after it the main Big Boss Man turns to Turner and I and he’s like, “I think you guys are great. What do you want to do?” And in my head I’m like, “Stick to the game plan. I don’t want to rustle any feathers here.” Turner immediately says, “Sir, we want to make a non-fiction Western.” [LAUGHS] Which is something we’ve been talking about for a long time. The guy was like, “Oh, shit! Let’s do that!” He gave us hundreds of thousands of dollars to go down to the border and do a pilot. Secretly we were always hoping that they didn’t pick us up so we could just use the money to make the film. And that’s what we did. I think they ended up going with a Kevin Smith comic book show.

H2N: We can credit Western to Kevin Smith.

BR: Yeah, I was going to put him in the thank you’s.

H2N: So, you guys stayed down there for thirteen months. What are the cost-benefits to being there for so long? Are there any downfalls?

BR: No, because it’s more about the experience for us, you know? I like living in different places and having those kind of experiences. Staying that long you become part of the community, you make friends, and people know you’re there and they know that you’re not just flying in, flying out to do some sting operation. People are like, “These guys are really invested in the story.” I think that goes a long way. And you’re there for anything that happens. We got our got ourselves a shitty apartment, and one of the trust-gaining exercises with Martin was he was really appalled with the way that Turner dressed, so he took him out shopping and made him look like a modern Western Man.

H2N: You passed the test.

BR: I guess. Certainly there are times where you miss your friends and you miss the parties and you miss your family and you miss getting laid. Especially at the end. But it’s totally worth it. It was one of the best years of my life.

H2N: When you’re in that situation, when do you know you’re done?

BR: With all three – well, now four – films, we just sort of looked at each other toward the end of a year and said, “Yeah, I think we got it. I think we got enough to make a film here.” It’s a weird negotiation, but it’s always just been a feeling where I think we’ve spent our time here and it feels right.

H2N: As an audience member you’re forced to accept that there’s a narrative going on around the subjects – the Cartel wars and the border closures – but at a certain point the movie just walks away from that narrative.

BR: Yeah, which some people weren’t that into.

H2N: Really? It fits in with and drifts in a way that a lot of narrative films are doing right now. Inherent Vice is one of those.

BR: Which, fuck – did you like that?

H2N: I watched it once, really liked it. Watched it a second time, literally gave me headache.

BR: I got kind of the same feeling. When I watched it the first time I loved it. It was so great. We watched it while we were making Contemporary Color. But then I watched it again and I wasn’t that into it. Now, I think we were a little high but…

H2N: Which should help!

BR: Which should help, but I found it frustrating.

H2N: Is there like another cut of Western that that feels more cartel and/or…

BR: Sensational? Sure. We could’ve made a very different movie. This is how we wanted to tell it because it felt more natural. There is definitely an HBO cut of this film. You could put your Michael Mann hat on and make that kind of movie but that’s just not the kind of art that we’re trying make. I like the quiet times. I found it to be more nerve-wracking when you wonder what is on the outside of the frame? I’ve found that certainly more terrifying than actually showing the face of it.

H2N: You present the experience as it was lived, how the paranoia felt rather than politicizing it or taking a seemingly objective point-of-view.

BR: We were watching a ton of westerns, everything we could get our hands on. Really the most meaningful thing that we got into was this professor, Richard Slotkin, who taught at Wesleyan University. I think he just retired. He wrote many books analyzing American history through film, particularly westerns. All of his lectures are online, so we continually watched his lectures then watched the films that he was referencing, because westerns are never about what they seem to be on the surface. When they’re good, they’re always actually talking about something else. The form is very, very interesting. It’s a platform to really speak to a great many things.

H2N: What do you think Western is talking about under the surface? What constitutes a modern-day western?

BR: That the John Wayne doesn’t always win, and the John Wayne can be a fragile figure. He is fallible. He can show weakness. These big brash men, they’re a reflection of the films that we’ve all seen. They’re embodying that kind of spirit and to see them weak and not have an answer is very interesting, right? And not have a satisfying conclusion. But that’s just life, you know? It just goes on. Martin drives away, Chad [Foster, Mayor of Eagle Pass] goes to church, and things will continue after that. There’s not some great resolution. They live in a very uncertain world and it’s OK to end on an uncertain note.

H2N: That comes through photographically as well. You convey the landscape as a metaphor for complete uncertainty. Were there any photographers that you were referencing in pre-production?

BR: Oh, William Eggleston all the time, right? I just heard a really funny story about Eggleston from [David] Byrne. I asked David who the weirdest cat he had on his True Stories shoot was, and without hesitation he said, “Bill Eggleston.” He said, “He’s one of my favorite photographers and I invited him down to do set photography. And he didn’t take one photo because he was always in his hotel room.” He didn’t take one photo.

H2N: As far as your films go, everything has been shot and released in order?

BR: Yes. We shot Tchoupitoulas, but we didn’t cut it because we immediately went to Texas. And then we shot there for a year, came back here to New Orleans, cut Tchoupitoulas, and Western just sat for a while. Then Contemporary Color has been very quick.

H2N: One year turn-around for the whole thing?

BR: It’ll be much less. Contemporary Color premieres in April, 2016 and the shows were in June, 2015.

H2N: For Western, what does a year-and-a-half-long edit look like?

BR: When we edit, it’s Monday through Saturday, usually ten to twelve hours each day. If we really get on a roll – this is fun, right? We are blessed to have this life in which we can do our hobby as our profession. So, whenever we work long hours there’s nothing to complain about. You’re in art class. Late in the day you have beers and start making a little bit more “creative” decisions, then you wake up in the morning and realize that they were really dumb drunk decisions. I don’t know other jobs that work like that.

H2N: What about being on the shoot? You’re living in an apartment. You’re not waking up, living with your subjects, right?

BR: Well, sometimes. It depends on what happened the night before. We spent many nights out on the ranch or in Mexico. That’s the beauty of the gig. You don’t know what each day’s going to bring. That’s why I like what we do rather than narrative. We don’t have a sheet that comes to us each morning that says you must be here, here, and here. Each day is new and exciting or boring, you just don’t know. We shoot every day and if it really is a slow day then I’ll use that time to import footage and make sure that we’re staying on top of things. We’re always going over and over the question: Why are we doing this? What do we intend to do? It’s the conversation the entire time.

H2N: Tell me about those conversations.

BR: Those conversations – we have sheets and sheets of paper all over the walls, so we’re constantly walking around. It’s going to make us sound like crazy people, but we’re walking about making sure that we’re staying true to what we’re doing, why we’re doing it, and these sheets get revised when new information comes in or when something happens. So, we’re always checking in with each other. The conversations will get personal at times, too, just making sure that Turner’s doing OK.

H2N: What about [Sound Mixer and Designer] Lawrence Everson? The sound design in Western had a particularly collage-like feel to it. What’s the process with him?

BR: We’re on our fourth film together with Lawrence. It’s a conversation with him well before we even start filming. So, while we’re shooting he’ll tell us to pick certain sounds up for him. When that gate sounds kind of nice when it closes, I’m going to get a couple versions of that. We present him with a whole library of sounds. Then he goes away for a while, does his thing and I’ll come in. It’s one of my favorite parts, that back-end sound mix. “We could really make that character pop in the background if we gave him this little noise.” It’s like making a second film, really.

H2N: I assume all of the radio transmissions in the film were culled as they were happening?

BR: Oh, yeah. One of the people who isn’t in the film was a woman that worked at the radio station. She’d call us and give us a heads up if anything was going down. So, we would turn the radio on and record it.

H2N: The most horrifying recording is the one with actual gunfire in it. Was that on the radio?

BR: No. That was a video that somebody in Piedras on the Mexican side had taken and given to us.

H2N: And you took out the visuals?

BR: We had that footage, but we all know what it looks like. I wanted it to hover outside the frame. I just found that so much more interesting. Again, it’s scarier not to see the shark.

H2N: The funny thing is: in Jaws you eventually see the shark.

BR: You do. [LAUGHS] I guess that that line of thinking only holds up so well.