A Conversation With Alden Peters (COMING OUT)

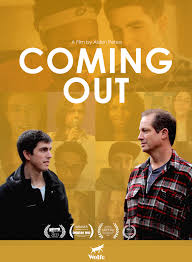

Coming Out, one of the most thought-provoking docs I caught at this year’s RiverRun International Film Festival (ironically in Winston-Salem, NC during the HB2 boycott) initially sounded like a navel-gazing gimmick. Filmmaker Alden Peters, a white guy from Seattle who passes as straight, documented his entire coming out process over several years – capturing the reactions of unsuspecting (and suspecting) loved ones on camera as he tells them that he’s gay.

Coming Out, one of the most thought-provoking docs I caught at this year’s RiverRun International Film Festival (ironically in Winston-Salem, NC during the HB2 boycott) initially sounded like a navel-gazing gimmick. Filmmaker Alden Peters, a white guy from Seattle who passes as straight, documented his entire coming out process over several years – capturing the reactions of unsuspecting (and suspecting) loved ones on camera as he tells them that he’s gay.

Yet what starts out as personal exploration soon becomes fascinatingly universal as Peters sharply broadens his scope to show how queer millennials still internalize society’s historical oppression even in the age of same-sex marriage. Part 21st-century time capsule (the doc includes clips of young LGBTQs coming out online) and part anthropological study (talking heads like Janet Mock chime in), Coming Out reveals that cultural expectations exert more pressure than any friend or family member ever could.

HtN was fortunate enough to chat with the self-reflective director/subject post fest.

Lauren Wissot: Why was it so important for you to film this rite of passage? Did the camera serve as a sort of emotional shield at all?

Alden Peters: Documenting my coming out process was important because I couldn’t find a documentary that showed the process over a span of years, exploring everything live, on camera, as it happened. I desperately wanted this type of film to exist, but it didn’t, so I set out to make it myself.

Documenting my coming out process definitely became an emotional shield during the experience. I had no idea how my friends and family would react, but I knew that I’d at least have footage if they reacted negatively. It allowed me to be much more confident during a very vulnerable time in my life. You probably wouldn’t guess it, because I made a feature documentary about myself, but I’m actually a shy, quiet person. I don’t share a lot of details about myself to anyone who isn’t a close friend. Having a camera present gave me the motivation to open up. There is a lot of agency in telling your own story on your own terms, so I felt more confident sharing vulnerabilities for the film. I temporarily forgot about my crippling self-doubt.

LW: Personally (as a genderqueer chick who escaped to NYC while still a teen in the late 80s) I’m shocked that coming out is even an issue in urban, leftwing segments of our population anymore. Who knew a white Seattleite with a supportive family would still struggle to come out in the 21st century (especially one who seems to have a diverse group of friends of different ethnicities)? Did you ever feel that perhaps, because of your relatively privileged background, coming to terms with your identity was not taken as seriously as, say, a LGBT person from a rural right-wing community?

AP: On paper, you’d look at my background and assume coming out would be easy. Then you watch the film, which is a positive film, and wonder what the issue was. Why would I be worried to come out to a liberal family from Seattle? This was going through my mind constantly as I created the film, both as a director and as someone going through a personal process. I constantly question whether or not my personal story is worthy. I still do. I faced the insecurity of sharing personal moments with others that anybody would go through when they’re in a film. But beyond that, I constantly wondered if my story was even necessary to tell. The representation of the LGBTQ community is overwhelmingly dominated by white, cisgender males. So why does a white, cisgender male, coming out story need to be told? I never was able to reconcile that, other than with the belief that more stories existing in the world is always better than fewer stories.

I also widened the perspective of the film by having people submit their coming out stories, which are included in the film. I speak to Dr. Ritch Savin-Williams, Zach Stafford, Greg Hinckley, Kayla Kearney, and Janet Mock. After filming our conversation, Janet told me that keeping the documentary more deeply personal will resonate with more people, and editors Megan Mancini and Alex Familian did just that. What we ended up with was a film with subtle nuance about internalized conflict, despite demographics and less social stigma in society.

LW: Your film touches upon an issue I hadn’t really pondered before – namely that homophobia can be internalized, even when everyone around the queer individual is accepting, because of society’s historical stigmatization of LGBTQ folks. Ingrained negative stereotypes exert more pressure than friends and family. (This also extends to racism, of course, as even black cops have been documented racially profiling African-American men.) When did you first become aware of the cultural baggage inherent in coming out?

AP: You really nailed it. I think of internalized homophobia as a form of socialization. We are bombarded with images and stories of what is “normal.” I started noticing it as soon as my friends and family supported me. I was wondering what was wrong with me. Why was I the one who had an issue with being gay, when others were supportive? Where did that come from? The benefit of exploring the coming out process in-depth for a film is that I constantly revisited and delved deeper into my feelings about the whole situation. What I found is that there was a part of me that saw being gay as abnormal. Plain and simple. I had no idea where that came from other than social stigma and social conditioning from a young age. This is apparent in the film during the early childhood, VHS scenes where my family is slightly mocking a gay man we had seen earlier that day. Mocking effeminate men is a learned behavior that compounds over the years until you learn that being gay is different. This can take years to overcome. It’s part of a longer personal process explored in the film that occurs after telling family and friends that I’m gay. It was a process of acknowledging and confronting early socialization of what is “normal” that we don’t talk about enough, both as a society and within the community itself.

LW: In the film you interview a sociologist who brings up sexual identity vs. gender expression, and says that acting in a “gender inappropriate way” is why folks get bullied – not because of their sexuality. I don’t think enough people (LGBTQ and straight) are aware of this, but it makes total sense. Sissy boys, drag queens and butch dykes are usually the ones who get beat up, not the gym bunnies and lipstick lesbians. As a guy who passed as straight for most of your life, do you think coming out would have been easier (harder? neither?) had your behavior been seen as more effeminate?

AP: My gender expression was something I consciously kept in check during adolescence, because it’s often a noticeable signifier of one’s perceived sexual orientation. Until speaking with Dr. Ritch Savin-Williams, I don’t think I had heard this articulated so clearly. As a kid, I was privileged to be able to express my gender in a way that fit societal gender norms. People just expected me to be straight. On the other hand, this made me constantly question whether or not I was gay, because I had no way of determining sexuality aside from conventional gender norms. It all blurred together, as it does for a lot of straight society, I think. So that prolonged my personal process of being in the closet. Who knows what would have been different if I had acted in a manner that resulted in people telling me I was gay before I knew it on my own.

LW: You also noted in the doc that, regarding your loved ones, “It’s a big change for me, but I never asked them if it’s a big change for them,” before going on to do just that. You even mention later on that this autobiographical film is ultimately not about you. So how do you think the coming out process would change if the focus shifted from the LGBTQ individual to straight society instead? (For as long as I can remember I’ve half-joked that I always assume someone is LGBTQ until proven otherwise.)

AP: Coming out is still a deeply intimate, personal experience that LGBTQ people define for and by ourselves. But also, for me, coming out is reflective of a society that expects conformity to the norm. If you’re different, you have to make a statement about your difference. You have to define yourself in a way that the “norm” understands. I’ve never been asked to define myself in LGBTQ circles, but I have to for straight society. We all do. If the focus of coming out is placed on straight society, you’d start to explore why society forces a community to define itself according to its narrow definitions of gender and sexuality instead of changing its own definitions to fit reality. It’s almost as if there’s nothing wrong with us, but there’s something wrong with society’s view of us, huh?

–Lauren Wissot