TIME IS LUCK (or, “a catechism of non-attachment”)

(For those lucky enough to live in or near New York the amazing BAMcinématek is offering up Heat & Vice: The Films of Michael Mann from February 5-16. Our Evan Louison drops some serious insight on a filmmaker who is clearly one of his favorites and even if you find yourself on the fence about Mann, this piece will give you much to chew on….or dream about…)

At the heart of The Lathe of Heaven (Ursula K. LeGuin, 1971), the mythology of an effective dream — one that can alter the current reality for the rest of the world — drives the moral narrative. While this dream type is LeGuin’s invention, the science of oneirology, or the study of dreams, defines authentic dreams as those derived from relevant experiences, and existing within that mainframe. The archetypical polar eclipse of this realm is the illusory dream state, which functions as a mainline for the glitches in the hardware, known as efficacy errors across the span of the internal circuitry of the human neurology. Quite literally, the bugs in the system. These latter altered levels of consciousness are where the impossible comes alive, where time slows, and images skip like stones across water. Rooted in the 17th century, the study is largely responsible for the zeitgeist of the dream sequence in film, along with the provenance of modern psychology. Given the glaring propensity of the West for emphatic focalization on the subconscious, it is no wonder that dreams have captured our attention for the better part of cinema’s infancy and pubescence.

At the heart of The Lathe of Heaven (Ursula K. LeGuin, 1971), the mythology of an effective dream — one that can alter the current reality for the rest of the world — drives the moral narrative. While this dream type is LeGuin’s invention, the science of oneirology, or the study of dreams, defines authentic dreams as those derived from relevant experiences, and existing within that mainframe. The archetypical polar eclipse of this realm is the illusory dream state, which functions as a mainline for the glitches in the hardware, known as efficacy errors across the span of the internal circuitry of the human neurology. Quite literally, the bugs in the system. These latter altered levels of consciousness are where the impossible comes alive, where time slows, and images skip like stones across water. Rooted in the 17th century, the study is largely responsible for the zeitgeist of the dream sequence in film, along with the provenance of modern psychology. Given the glaring propensity of the West for emphatic focalization on the subconscious, it is no wonder that dreams have captured our attention for the better part of cinema’s infancy and pubescence.

“My film has the passions that happen in dreams sometimes when you’re grabbed in the middle of a dream and yanked into places you either want to get out of or you never want to leave… It’s a penetration of psychological realities….one huge dilation of space and time into a dream reality.”

— Michael Mann, 1981

Oneiric compassion for a narrative’s subjects, treating their trajectories with an augmented, hyperkinetic air has been the touchstone of Chicago born, London educated, astral vicelord Michael Mann’s cinematic architecture. By affecting the human gaze of his cinema’s lens and focus into a paradigmatic series of aesthetic tropes, his narratives take on an oneirogenic (or dream facilitatory) purpose as their sole burden — to shift the viewer from this reality into one where time slows and overlaps while action, suspense, and high drama escalate. The tense audacious building and tragic, rapid destruction of each character’s dreams, along with the collective dreamlife of the audience, gives his feature and television work the appearance of resembling some penny arcade – crystal ball hybrid (see: interobject) which allows the viewer the position of surveillance over his characters’ struggle and triumph, no matter how doomed.

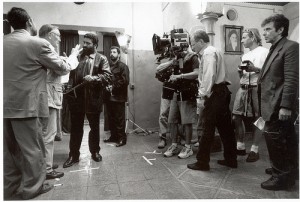

Mann’s films, collected in a retrospective series by BamCinematek as HEAT and VICE, beginning February 5th, have served as a bedrock for the purpose of the cinematic form propped up as an elevated experience, and their empathic characterization, with portraits of wounded men, urban warriors, criminals, lawmen, their victims, and their families, is so rich with color and precision they seem ripped from the headlines and the stuff of dreams all at once, the substances our fiction and non-fiction worlds consume in hellbent, open fisted mouthfuls.

If oneirology defines a dream of rapture as one in which the dreamer accepts the new reality as “more real than real,” and a veridical dream one of prophesy, which foretells and reveals through the process known as oneiromancy (i.e. We dreamed this before it occurred, we knew this would happen…), then the hypnagogia of modern cinema, existing in our minds on the “threshold of consciousness”, must allow for an oneirogenic environment to take hold of its visitor, allowing neologisms and interobjects to be created within the viewing experience as character and narrative analogs are drawn to the audience’s inner and waking life. It should provoke hypnopomp, a drowsiness that sets in in the retreat from the darkened movie house to the harsh light of the living, a feeling of being roused from a dream we did not realize we were so deeply immersed within until the spell was lifted. This immersion, and the phenomenological character of the process of narrative film, in turn becomes one both edifying and mystifying as a result. Like the sudden awareness of a false awakening.

Halfway between Murnau and Kubrick in the balance of cinema’s scales, Michael Mann’s monomaniacally obsessive pursuit of dream state portrayal (and all its increment implications in reality), through the prism of Marx’ Labor Theory of Value (or LTV, in which commodities’ value is defined as “objectively measured by the average number of labor hours required to produce them”), has produced more hyperlink connections between our collective memory and the worldwide digital image databank of the modern city, technology, and urban warfare than any other living director, and his iconic contributions to the genre of crime-fiction and vivid representations of violence in cinema surely cause his derivative progeny (many they are) to turn pale beyond compare.

His characters, all possessing of some level of the pathos and obsession which drives his own fanatical investment in background development and secret histories for his performers and writing, ricochet off the screen in time with their darkened visages’ pained expressions at the vacancy of existing with limited time, within the limits of chance and fate, and to quote the master, like “a needle starting at zero and going the other way, a double blank…”

“I’m just not interested in “passive” filmmaking, in a film that’s precious and small and where it’s up to the audience to bring themselves to the movie. I want to bombard an audience – a very active, aggressive type of seduction. I want to manipulate an audience’s feelings for the same reasons that composers write symphonies.”

Mann’s altered realities take shape from the characters that reside within their confines, and are more oft than not, entirely realist in their grammar, aside from when the superhuman will to triumph seems to intervene, as in Collateral and Heat, and from the out and out supernatural anomaly that is The Keep, to this date the director’s sole departure from the reality of phone lines, the streets, and men with significant attachment disorders, driven by lusts for wealth and yes, dreams. Mann said two years ago of his film The Insider, “It’s not just accurate — it’s authentic.” It is certainly possible to argue in turn that the same can be said for each of his pictures. Amidst the flying sparks, corrupted pixels, hail of bullets, and endless reversals of fortune that become the makeup of his fever dreams, they are all intensely logical, no matter how implausible they may seem. Last year, Bilge Ebiri, probably the only writer I can seem to find with as much of an unhealthy obsession with Mann as myself, noted that “Unquantifiable Connections could be the alternate title of every Michael Mann movie.” I would offer Cops and Robbers, Men at Work, and Have Trigger, Will Travel as runners-up.

His people are two and three time losers, safecrackers, thieves on the prowl and on the strong, gambling addicts who can’t get straight, vice cops, gangsters, detectives, serial killers, reporters, cultural firebrands, darkweb cyberterrorists, assassins, and in general, laborers — the lives of those residing on the myriad frontlines of life as modern warfare. His characters are painstakingly constructed, deprived of the suspension of disbelief begotten from any acceptance of fiction automatically as artifice, and as Mann told James Caan, reflecting on his performance as Frank Hohimer in Thief (1981), “Because he’s a delimited man given his history, the only thing he can see for himself to do is to rid himself of everything he’s cared about so that he’s reduced to that nihilistic state where there is no meaning in his life…There wasn’t a gesture you did or a tool you used or an attitude you had that wasn’t anchored in some history.” And yet, it is also the archetypical Mann dialogue that seems to emanate from every picture he made, with the same wisdom bleeding orifices formed by different mouths, some on either side of the law, an interchangeability implying fate and destiny’s cruel, casual distribution. When cops and robbers alike can all feel the same — that Time is Luck — it connotes a universally benevolent sense of attention to each individual character and microcosmic plot line, not myopia as some have suggested previously. But within the architecture, amid the super unleaded cool of his visuals, Mann’s background betrays an empathic profiler’s bent early on. At Loyola Marymount two years ago, he spoke at length about his formative years in Chicago and at the University of Wisconsin, pre-film school:

“I was everything from a taxi cab driver to a short order cook to a janitor…a film that came out in 1956 called Blackboard Jungle… scared everybody of my parents’ generation that their kids were going to look like Elvis Presley and run around and join gangs. So my father’s plan [was] that I work…I found myself being one of very few people who had any experience on the street, and who had any understanding of what life was on the West Side of Chicago for construction workers, or tenements or anything, or itinerant groups of fast food chefs who were mostly Scotch-Irish, Appalachian, and how they moved around…There were so many dynamics. I found myself in a population of students who, for the most part, were unexposed and uninitiated to anything to do with even the smattering of real life that I had experienced in small ways as an 18- or 19-year-old…

[At University of Wisconsin] I remember clearly, I was walking down Bascom Hill. It was about 10 degrees below zero, one of these Midwestern, clear nights where all the stars were out. And the air was dry, about 10:30 p.m. I was halfway down the hill. And it just occurred to me, “You’re going to make films. This is what you want to do.” It just kind of hit me. This is what you’re doing. It was just such a total being overcome by a powerful, powerful realization and an emotion and there was not even a question. So by the time I got to the bottom of the hill, it was done. This is what I was going to do with my life. And I consider myself extremely fortunate that that happened, because I am suited for it, neurochemically, neurological, you know, culturally inherited dynamics. I found myself at my age now having had a life that I absolutely was suited for… I’ll hear a fragment of conversation, I’ll imagine somebody’s character. It’s involuntary. I can’t really control it.”

The level of automaticity that Mann’s dramatis personae display is a cumulative result of the sequential levels of his process of discovery and immersion in the quest for verisimilitude amidst the architecture and stylization at play. His early work was informed by a handful of hard men, a veritable rogue’s gallery of the 20th century — convicted murderer Dennis Wayne Wallace (Red Dragon), LAPD’s Tom Elfmont (LA Takedown, Robbery Homicide Division, Heat, Collateral), former SAS members Andy McNab and Mick Gould (Heat, Collateral), Chuck Adamson (Thief, Crimestory), criminal / writer hero Edward Bunker (Straight Time, Heat), and jewel thief John Allen Seybold — who provides Caan’s Frank w/his pen name, the same name he evaded warrants under as he served in advisor capacity on Thief’s set. He populated his cities and streets capes with well-worn, weathered faces belonging to Miguel Pinero and Dennis Farina, torn from the cloth of the same lives they were cast to portray. Its always a stunning, uncanny presentation of skill, focus, and study — gamesmanship and tradecraft through and through — no action taken on his performers’ part going without careful consideration and hypothesis. To watch Caan clear the room with exacting, 2nd nature grace as he stalks Robert Prosky’s Leo, the way he handles the thermal lance in his last score, is to watch that process of immersion pay off.

It has been said elsewhere that the repercussions of the Downtown LA shootout sequence at Heat’s phi-point were not to be felt for several years. Most notably in 2002, with the Cali, Colombian R15 armored truck heist, which mimicked the film’s opening identically and to great success, and perhaps most tragically in the now infamous North Hollywood Shootout, where previously unapprehended High Incident Bandits Larry Phillips, Jr. and Emil Mătăsăreanu finally succumbed to their luck and time running out. Both were scenarios seen as too dreamlike to be real, save for perhaps oneiromancy at work. Perhaps Heat is a rapturous, veridical lifeline. As I’ve written in these pages before, “You believe the lawlessness of the place because it feels like a place so big that things like this could happen there. Like they do happen.” Of Phillips and Mătăsăreanu, Mann could only lament in retrospect “They made one mistake — assaulting the police instead of fleeing the police. The whole point is to shoot your way out. You’re supposed to leave because police assets accrue rapidly, the longer you stay. You’re assaulting the police to shoot your way out but the point is to get out. They just stood around.” Again, there’s that sympathy for the devil.

When Mann revealed years ago that Special Forces training now involved cadets attempting to emulate Val Kilmer’s signature fire-reverse-fire-one handed reload pattern move perfectly, much had already been made of his drive for precise depiction of physical task and technical proficiency in his cast, but rarely for its honest source — what he described sincerely as a “serious professional admiration for a guy who was a really good professional thief.” This admiration leaves us with the undeniable effect of believing what we’re seeing, no matter that it is construction and fantasia. Mann’s devotion to his characters, and subsequently to his performers, is elemental and pervades his work in earnest, to the point of demanding indulgence for the more egregious characterizations or misfires.

Most often, his characters operate under a version of Highway Hypnosis wherein they act and react on instinct, training, and conditioning, like animals more than the at least technically brilliant men they are. It is the white line fever of the world weary, the thousand yard stare of trauma and trouble, a singularity of dedication and a set of razor-fine crosshairs. In his limited, battle scarred vision of the landscape, the oneironaut sees nothing but choices and available escape routes. They don’t think, they don’t talk — they just do as they do. Fates intertwined, cosmic coincidence — all that. They only live as far as they can drag themselves, and don’t dream lest they expose a vulnerability through delusional attachment to hope and the potential of the future. Live by the sword, die by it. It rains, you get wet. Hypnotic Dissociation : One consciousness driving the car, one consciousness dealing with what happens when they get there. The rapid learning profile which Mann clearly seeks to tap in each of his performers is the eventual conduit for this energy of embodiment, immersion, and execution. It’s not just accurate, it’s authentic. If this is a dream, and all we can do is work — then what we do for a living is that much more important

Manhunter’s Tom Noonan in recent years recalled a moment of connexion with the director, one that seemed to resonate, no matter the absurdity, on some scale of devotion to this process of perfection and integrity achieved through accurate measurement and plotting. Noonan’s character of Francis Dolarhyde, scarred from a cleft palate and a seriously trigger ridden history of abuse (and paraphilia), in his mind required absolute isolation to achieve. Referring to Mann’s interest in accommodating his methodology:

“He said OK, and this memo went out to everybody in the cast and crew, saying “No one can see Tom again. No one will talk to Tom. Everybody will avoid him.” … Over time, it got crazier and crazier. There was a PA walking 20 feet in front of me and 20 feet behind, so I never ran into anybody. It was interesting, but it was really odd….Michael would come some days and knock on the door and say, “Francis, it’s Michael.” I said, “OK,” and he would come in and we would sit in the dark together in my camper for long periods of time and not speak. It was really cool. I had never been in another movie, really, and I felt it was going good; the director was hanging out in my camper with me, not talking.”

Leave Now. Life is Short. Time is Luck. Things go wrong. The odds catch up.

Probability is like gravity — And you cannot negotiate with gravity.

—Evan Louison

Aforementioned work not included in BAM‘s series that we implore the reader to see out includes the incredible, shot at Folsom Prison The Jericho Mile (w/appearances by a young Brian Dennehy & the late Geoffrey Lewis), the classic Chicago procedural Crime Story (pilot directed by Abel Ferrara, featuring virtually every character actor in existence, available onHulu), the original Miami Vice series (also on Hulu), & the sadly overlooked Robbery Homicide Division, starring Tom Sizemore & cancelled after one season (NYC/LA cinephile hint: The Paley Center’s Scholar Room).