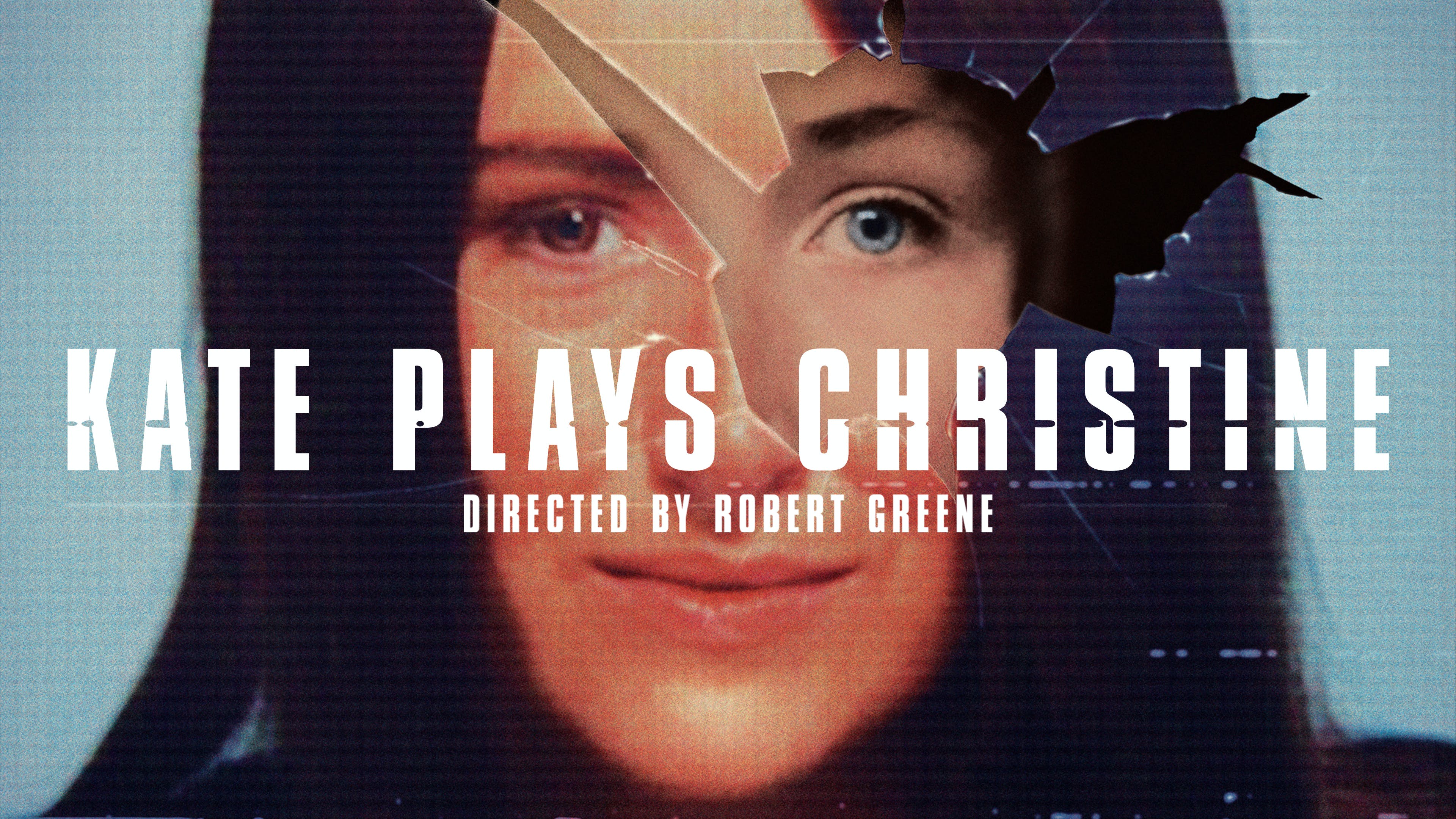

ROBERT GREENE’S “KATE PLAYS CHRISTINE” IS ANOTHER DOCUMENTARY EXPERIMENT

(HtN contributor Ray Lobo is a big fan of the films of Robert Greene. So much so, he’s trotting out this 3-part series on Greene’s films Actress, Kate Plays Christine and Bisbee ’17. Like what you see here on Hammer to Nail? Why not give just $1.00 per month via Patreon to help keep us going?)

Antonio Campos’ 2016 biopic Christine gave us a remarkable performance by Rebecca Hall. Christine recounts the shocking on-air suicide of Sarasota news reporter Christine Chubbuck. I do not avoid movies with dark subject matter as long as they have aesthetically redeeming qualities. Apart from the obvious darkness of an on-air suicide, Christine deals with the demoralizing sexism women faced in newsrooms and workplaces in the 70s. Robert Greene’s Kate Plays Christine was released the same year as Christine. There was great buzz surrounding Kate Plays Christine. I could not, however, bring myself to watch a second movie, this one a documentary, on Christine Chubbuck’s suicide. After a five-year breather from the Chubbuck case, I finally came around to Kate Plays Christine this year. I was riveted by Kate Lyn Sheil’s “performance” – the reasons for the scare quotes will become apparent later – and especially by Greene’s technique of kneading documentaries into new shapes.

Kate Plays Christine revolves around Sheil’s research and work in playing the role of Chubbuck. It is never clear whether this is an actual role Sheil will play or if the arduous path toward her transformation into Chubbuck –interviewing Chubbuck’s colleagues, speaking to specialists on depression and suicide, going to the same gun store where Chubbuck bought her weapon, even spray tanning herself to look more like Chubbuck – is the subject of Green’s “documentary.”

The blurred line between “reality” and “role” was explored in Greene’s previous work, Actress. Kate Plays Christine is an intensified exploration, by both director and lead, of those blurred lines. The only existing tape of Chubbuck’s suicide is in the custody of the former station owner’s widow. Sheil must piece together Chubbuck’s life from those who knew her, or better said, those who thought they knew her. In what is perhaps the epitome of hyperrealism, Sheil bases her role on the only existing footage of Chubbuck, footage in which Chubbuck is playing the role of newscaster.

Chubbuck’s last words before pulling the trigger were: “In keeping with Channel 40’s policy of bringing you the latest in ‘blood and guts’ and in living color, you are going to see another first – an attempted suicide.” Chubbuck’s coda was a final protest against the personal and professional pressures that asphyxiated her. Chubbuck worked in a news environment that breathlessly pursued the lowest common denominator – “blood and guts.” The blood and guts of others, their real physical pain and erasure of life, creates an appalling dichotomy with newsroom talk of ratings, fake smiles and scowls from individuals playing the role of “newscaster,” and awkward segues to weather and sports. Chubbuck worked in a station in which the weather-anchor was a former Ms. Florida. Chubbuck wanted to be a serious journalist. Her colleagues, in what feels like a lazy description tinged with misogyny, said she was too “hard and edgy.”

Chubbuck’s personal life had a haunting melody. Chubbuck was a virgin. She had an unrequited crush on a co-worker. She had been to several psychotherapy sessions before her suicide. Sheil goes deeper and deeper into her role by roaming around Sarasota, feeling its dark corners, and talking to its inhabitants. She visits gun stores, nightclubs, and wig shops. It is, in fact, a wig shop owner that tells Sheil that she is “much more beautiful” than the late Chubbuck. It becomes apparent that today, just as much as in the 70s, women are still evaluated based on looks. Florida – those of us who live here know – is a swirl of fun-in-the sun kitsch and gloom. Florida, with its strip malls, tacky beachside hotels, snowbirds, transplants, partyers, and tourists; can be a dark and transient place. It is difficult to feel anything that passes for a sense of community. It is hard to date, to forge meaningful relationships. Florida, with all its attributes, likely did not help an introvert like Chubbuck.

Sheil starts taking on Chubbuck’s despondency; their roles overlap. One is reminded of merged identities in film – Bergman’s Persona and Lynch’s Mulholland Drive. Greene and Sheil masterfully throw off the viewer’s identity GPS – has Sheil become her role, has she become Chubbuck, has Sheil’s role become Chubbuck’s newscaster role in a case of role mimicking role? These may seem like metaphysical musings, but if you consider the slipperiness of a “true” self and the roles we play every day, can we ever truly point at a unified self? This is the question Greene returns to in his documentaries – Actress, Kate Plays Christine, and Bisbee’17.

By the time Sheil gets to act out Chubbuck’s suicide, her immersion into the role does not blind her to the fact that this final scene is a repetition of the blood and guts formula, one last exploitation of Chubbuck. Sheil hesitates pulling the trigger of the stunt gun. She points the camera at the fourth wall, at us. She gathers herself and finishes out the scene, the blowing of her brains. Sheil lashes out: “Are you happy now? You’re all a bunch of f -ng sadists.” Is she angry at Greene, at us, at the world? Some may accuse Greene of exploiting the Chubbuck case, of exploiting Sheil. The questions multiply – is Greene yet another gawker of blood and guts, another director pushing an actress to the point of emotional collapse, or has he perhaps crafted the most layered and profound analysis of the American death drive?

– Ray Lobo (@RayLobo13)