Revisiting Milgram and Zimbardo’s Human Behavior Experiments

(With the release of Kyle Patrick Alvarez’s Stanford Prison Experiment and the upcoming Experimenter from Michael Almereyda, our own Lauren Wissot scratches an itch that’s been under her skin for some time. Are Stanley Milgram and Philip Zimbardo’s (in)famous psychological studies on human nature flawed at their core? Read on and chime in at our Facebook Page)

Several years ago I happened upon a Rolling Stone magazine article that put forth a fascinating idea. It described a little known “experiment” done in the 80s just as the AIDS epidemic had begun its chokehold on the gay community. Gay Men’s Health Crisis and other likeminded organizations desperately needed money for research. However, unless the public was personally touched by the disease (at that time largely confined to homosexual men, Haitians and drug addicts – not a particularly influential lobbying contingent), resources were bound to go to more mainstream causes like cancer and heart disease, which personally affected the majority of donors. So the AIDS fundraisers did something ingenious, repositioning the disease in the public mind. Instead of stating the facts – that unless you were a gay man, an IV drug user or a blood transfusion recipient your chances of getting AIDS were slim to nil – they focused on the idea that “anyone” can get AIDS, from the littlest Ryan White to the oldest Arthur Ashe. AIDS doesn’t discriminate with regards to race, age, sex or sexual persuasion, which is technically true. If you’re a human being you can get AIDS, just like if you skydive you can get killed jumping from a plane. We’re all equal opportunity employees for death, but what this truth conveniently ignores is that most of us will not die skydiving because we don’t skydive – just like most people in the 80s were never going to get (nor know of anyone afflicted with) AIDS.

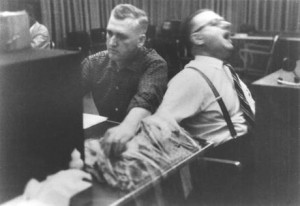

I thought of this marketing strategy as I revisited Alex Gibney’s 2006 documentary The Human Behavior Experiments, which explores how otherwise good, decent, law abiding citizens will do the unthinkable when guided by a strong authority figure, or not do the right thing when given “permission” by the presence of others reacting unconscionably. Gibney – whose HBO doc Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief made a splash back at Sundance – uses data obtained in the famed Milgram and Zimbardo experiments. The experiment done by Milgram (recently the subject of Michael Almereyda’s Peter Sarsgaard-starring biopic Experimenter, which also premiered at Sundance) showed how research volunteers were willing to deliver painful electric shocks to a person if egged on by the scientist in control. Zimbardo, for his part, set up a mock prison filled with research volunteers that quickly became a rat lab precursor to Abu Ghraib (and, in a bizarre twist, is the subject of yet another Park City premiere – Kyle Patrick Alvarez’s The Stanford Prison Experiment, which IFC picked up and will open theatrically on July 17th). Sundance buzz aside, I believe the outcomes of both men’s experiments to be the result of flawed methodology, an accidental AIDS fundraising-type scheme that conveniently edits out certain truths.

The primary question both Milgram and Zimbardo failed to take into account is, what type of person volunteers to participate in an experiment? An everyday, normal Joe, just like you and me? If this were the case we all would be volunteering for experiments – just like we all would be volunteering for the army, fire and police departments. No, the people who volunteer for experiments (let’s call it the “volunteer personality”) are the exception in society, not the rule. They are the type of person that want to serve a cause greater than themselves, desire the camaraderie of the platoon, the engine or the frat house, have a certain respect for authority. (Or if you’re inclined to cynicism, those hard luck cases that need the meager per diem university studies offer.) The percentage of Americans drawn to this mode of thinking, while perhaps great, hardly constitutes the majority. No, the majority has never joined a fraternity nor sorority, the armed forces nor police and fire units – because their mindset is not conducive to this environment. Follow this line of thinking and one realizes that if it’s the “volunteer personality” that join experiments and the army then it is not “anyone” who has the potential to exhibit the behaviors peculiar to Milgram’s and Zimbardo’s experiments and to Abu Ghraib. An everyday Joe could no sooner have committed prison atrocities than the virgin teenage girl down the street could contract AIDS.

That certain individuals drawn to the camaraderie of a group are also driven by a longing for power over that group, is the dark side of this equation. These are the “bad apples” like Hitler (the man who greatly influenced Milgram’s thinking), and the volunteer in Zimbardo’s experiment who made it his goal to be the “baddest” prison guard of the bunch, that are now in a position to shepherd the remaining whose “volunteer personality” drew them in. (And the “good Germans” who looked away? Could it possibly be something as banal as self-preservation in the face of a steamroller?) But Hitler, while an atrocious exception, was merely a fluke writ large, evidenced by the armed forces around the world that with the same “volunteer personality” as his followers turned this into a strength to bring him down. This “volunteer personality” is an integral part of society. The people who join the army and end up torturing innocent Iraqis are the flip side of firefighters who rush into burning buildings without thinking twice. They all do what is acceptable group behavior in those circumstances. But, once again, to say that simply anyone in the general population has the personality to engage in any of these acts, awful or heroic, is nonsense.

Similarly, the “McDonald’s incident” detailed in Gibney’s 2006 doc (and which is the subject of Craig Zobel’s docudrama Compliance, a 2012 Sundance premiere – yes, Milgram and Zimbardo are big with the indie hipster crowd) in which an assistant manager was led to strip search a teenage employee by a phone prankster, is misleading. It takes a certain personality type – clearly not just anyone in society – to be convinced to do such a heinous thing. It reminded me of the stories on the news that scream, “Email identity scam – it could happen to you!” Most people delete their junk mail so, no, it could not happen to them. The people who open their junk mail and are ripe for scammers are the same people that strip-search employees at the behest of a fake officer on the phone. The majority of society will never be scammed, never be tricked into ignoring their conscience. (That the fake officer scammed 70-100 restaurant employees only proves that he was tricking the same personality type – conducive to that line of work – over and over again. And when the assistant manager’s fiancé ultimately was given “permission” by the voice on the phone to partake of oral sex he really was revealing his “bad apple” colors.)

Fortunately, I did find one study broached by The Human Behavior Experiments that held up in the light of day. Kitty Genovese who was murdered in front of 38 witnesses was as much a victim of the circumstances in NYC then as she was of a mentally deranged man. The city since has cleaned up, the crime rates plummeted, and our collective consciousness, our notions of both proper and unacceptable behavior, has changed. The “broken windows” theory Giuliani loved so much is really based on the assumption that if lawlessness as unacceptable behavior can be “marketed” to society then society will start obeying the law. When Kitty Genovese was murdered it was acceptable behavior in NYC to mind one’s own business (because not minding one’s own business could get you killed!) A murder like that could not happen today because we’ve long since bought Giuliani’s “product,” the behavior of the majority has shifted. I say it’s high time for the outmoded thinking of Milgram and Zimbardo to shift as well.

– Lauren Wissot