A Conversation with Michael Almereyda (TESLA)

Near the conclusion of Michael Almereyda’s beguiling Tesla, the title character, played mysterious mystical perfect Ethan Hawke, steps up to the mic for a karaoke version of Everybody Wants To Rule The World by Tears For Fears. His voice is frail, but the message cannot be lost “welcome to your world, there’s no turning back…It’s my own design, It’s my own remorse…I can’t stand this indecision, Married with a lack of vision, Everybody wants to rule the world.” One of many flights of fancy such as Ann Morgan researching characters on her laptop, the writer/director continually reminds us that any biopic is shaped by the circumstances of those telling the story. If you’ve ever used a radio, a cellphone, or even electricity, you’ve plugged into the legacy of Nikola Tesla. Whether we like it or not, and without much reward to Tesla, we are living in a world molded by Tesla.

Almereyda has been ‘experimenting’ with Tesla since his teenage years, when he came across the Prodigal Genius by John O’Neill. “The portrait it presents of Tesla is a very heroic one,” the director explains, “I think it corresponded to my own unhappy sense of rebellion as a teenager.” I had a chance to chat with Almereyda just before the release on his film and discuss (our admittedly mutual) fascination with the man responsible for design of the modern alternating current (AC) electricity supply system.

The inception of the film can be traced back to chance meeting poolside with Polish director Jerzy Skolimowski who had just won best screenplay at the 1982 Cannes Film Festival for Moonlighting starring a young Jeremy Irons. “It’s preposterous to think about now,” remembers Almereyda, “but his main conviction regarding Tesla came from the fact that he was friendly with Jack Nicholson and Nicholson had heard about Tesla from a cab driver.” Overhearing the conversation, the young writer/director, several years before his first film, pitched him his Tesla script, Skolimowski read it, and in a few months, he was flying to London to work with him on script revisions.

Unfortunately, like many of Tesla’s own projects, the financing fell through before they got very far. The script went into a drawer but the project got Almereyda an agent and intrigue the title character generated chased him through the years. After two Sundance hits (The Experimenter and Marjorie Prime), he returned to Tesla. Of course, Tesla has been on screen before, notably recently in Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige and Alfonso Gomez-Rejon’s The Current War (which didn’t come out until after Almereyda had shot his film). Of course neither of those films, or many before at all, focused on Tesla as primary character. “I was focused on trying to get inside the real person instead of using him as a talisman or a plot point,” he says. The only other true attempt at a Tesla biopic, Krsto Papić’s The Secret Life of Nikola Tesla, can be watched for free on You Tube. “It features Orson Wells as J.P. Morgan and his girlfriend and companion and collaborator, Oja Kodar, playing Katharine Johnson,” says Almereyda; “I have sentimental feelings about that movie –it’s so clumsy and earnest, presenting a picture of Tesla as a persecuted victim. A quaint, simplified portrait, but I actually like it.”

In Almereyda’s Tesla, the title character is less a persecuted victim and more a quixotic idealist. After taking money from Morgan to develop what the industrialist hoped would be a way to send stock prices across the Atlantic, Tesla seems undeterred as Marconi develops radio utilizing several of Tesla’s own patents. Tesla’s efforts focused on building a conduction-based power distribution system, which of course would have ended the ability to charge for electricity.

His personal disappointment of being unable to develop a friendship with Thomas Edison, a fellow genius as he views him, belies the fundamental differences between the two men. Edison’s most important inventions – the light bulb, the phonograph and moving pictures – were all things other men pursued. If Edison hadn’t invented them, someone else would have. In contrast, Tesla’s alternating-current motor and first-of-its-kind hydroelectric power plant at Niagara Falls were disruptive technologies that changed the world. He was a futurist, a man who created need instead of following it.

For those who know Almereyda’s work, seeing Ethan Hawke face off against Kyle MacLachlan like they did in his Hamlet is a special treat. The relationship between the two inventors is nuanced, and rather Shakespearian in scope. “It’s great to get the band back together, as Kyle himself said,” comments the director, countering, “I’m not sure it is Shakespearean, but I’d like to think the two films will be shown together sometime.” Because of scheduling, the production had to kick off the shooting with the Edison scenes, giving “everyone a shot of energy. Ethan and Kyle were happy to be in the same frame together, and I was happy to have orchestrated it.”

These repeat pairings often bring – sorry to have to say it – electricity to screen, and this is no exception. The actors’ comfort with each other allows them to really face off because it’s not just an antagonist relationship, it’s also a mentorship gone wrong. When Tesla goes to work for Edison, he was twenty-eight. Edison, just nine older than Tesla, was already one of the most famous people in the world. “There was an inherent imbalance in that relationship,” says Almereyda. “It’s poignant to recognize that,” he continues; “Edison’s wife died at that same period. That must have had an effect on how they related, or how they didn’t connect at all.”

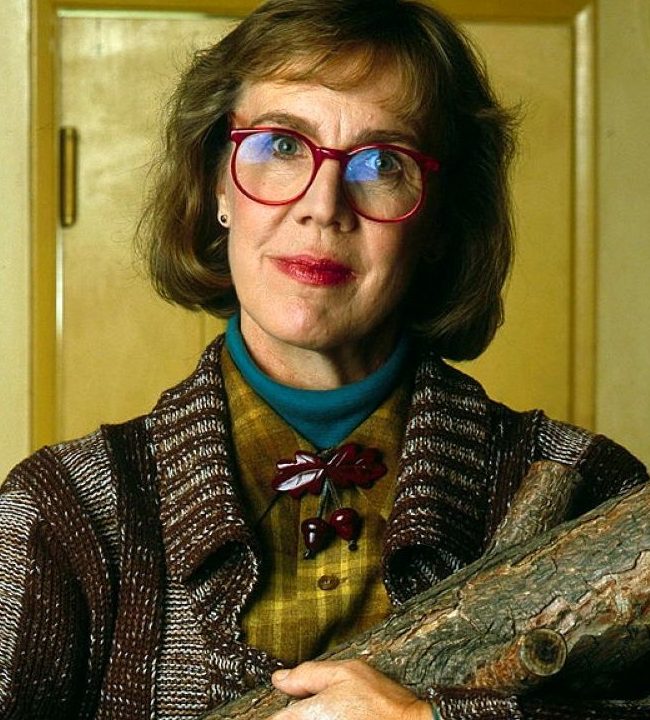

Filmmaker Michael Almereyda

Hawke’s Tesla feels slighted by Edison – underestimated and full of grievances. However, we may never know the intricacies of the relationship. Almereyda points out an anecdote he came across in a book published after shooting had finished: Edison attended one of Tesla’s lectures in 1900 or 1901. “Edison was a little late and Tesla got off the stage, shook his hand and guided him to his seat to a standing ovation,” says the director, “so how much of a villain and a nemesis could he have been?” This, for Almereyda, is a perfect example that, as he tells me, “history is a living, flexible thing and there’s plenty of room for confusion.”

The murky details of Tesla’s personal life allow the film to explore relationships that have been suggested to have existed in varying degrees, from chance one-off meeting, to profound influence. For example, some historians relate the Sarah Bernhardt/Nikola Tesla meeting as nothing more than a dropped handkerchief. For others, she is the unobtainable, a female embodiment of the scientific progress he sought. “I think she embodies a kind of personal risk-taking that Tesla was afraid of,” explains Almereyda, “Sarah Bernhardt embodies physicality and sensuality and an emotional openness that Tesla avoided in his life.” In his film, Bernhardt is the closest Tesla comes to being pulled out of logic, but he never crosses over out of his own safety.

As a storyteller, the director did not want women to be crowded out of Tesla’s story. In fact, the film is told through the perspective of Anne Morgan. “Anne wasn’t in my first draft,” admits Almereyda, “but over time, I thought Anne’s perspective would be close to my own, trying to understand why he never allowed or accepted love in his life.” Again, Ann’s encounters with Tesla are hazy. Most historians believe Tesla was using her to get to her very rich father, but for the director, this is poignant in itself. “As she got older, she was an activist for women’s rights,” Almereyda expands, “and she became more of a philanthropist, using her money in a way that seemed heroic to me. She also, as the film testifies, acknowledged that her own sexual inclination was for other women. So I was intrigued by that context, wanted to bring that to bear.” Like Tesla, Ann exists in the film out of time, backed up by technology built on ideas of Tesla’s own devising, fusing her voice with our contemporary perspective.

This is what is so enigmatic and brilliant about the film. Right from the open Ann Morgan lets the audience know this isn’t going to be your typical biopic. Tesla was a man of our time. Not necessarily a man of the time he was in.

“I wouldn’t call him our first modern man,” Almereyda says, “but he was, by his own definition, a man ahead of his own time.” He quickly follows up: “though, honestly, what’s frustrating is that he was also entrenched in a Victorian sensibility, very prim and closed and full of pretense.” For the director, Tesla was concurrently full of fear, yet completely brave, far-seeing, visionary. “The film presents a balance,” he says, “attempting to be true to how complicated he was.”

Michael Almereyda’s Tesla is available now on VOD via IFC Films