A Conversation With Mike Plunkett (SALERO)

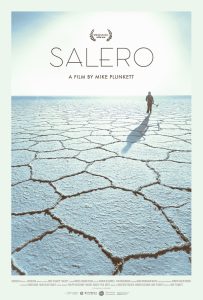

I met with director Mike Plunkett at the Maryland Film Festival on Saturday, May 7, 2016, to discuss his documentary feature Salero (the title means “salt gatherer”), about a vanishing way of life on the salt flats of Bolivia, and for which I also wrote a review. Here is a condensed digest of that conversation.

Hammer to Nail: I really liked your film. It’s such a fascinating subject. How did you discover it, both the Salar de Uyuni [the salt flats] and Moisés [the main protagonist]? How did you find the man and the place?

MP: So back in 2009, it was around the time when the auto industry was sort of reinventing itself and electric cars were big and they were using these lithium batteries, and lithium was a very hot – and still is very hot – commodity. Bolivia and the Salar, because of the lithium reserves became took center stage and there were all these front-page articles in major publications, so I got exposed to this crazy, alien landscape through those articles. I’d never even heard of this place. But I saw these images. And it was really the images of the landscape that drew me in as opposed to the geopolitics. And I decided, sort of on a whim, to go to this place. I had spent some time in South America, but this was like another planet. I said, I need to go down there, I need to experience this landscape. Maybe there’s a story, maybe not. I don’t know.

MP: So back in 2009, it was around the time when the auto industry was sort of reinventing itself and electric cars were big and they were using these lithium batteries, and lithium was a very hot – and still is very hot – commodity. Bolivia and the Salar, because of the lithium reserves became took center stage and there were all these front-page articles in major publications, so I got exposed to this crazy, alien landscape through those articles. I’d never even heard of this place. But I saw these images. And it was really the images of the landscape that drew me in as opposed to the geopolitics. And I decided, sort of on a whim, to go to this place. I had spent some time in South America, but this was like another planet. I said, I need to go down there, I need to experience this landscape. Maybe there’s a story, maybe not. I don’t know.

So I tracked down one of the photographers who had taken some of the photos that really struck me, and it turned out that he was the former videographer for Bolivian President Evo Morales, and he knew all these people in the government and he had very good connections. His sister was a fixer living in the region, and any of the news agencies that were going down there to shoot – ABC, BBC – they would hook up with her, and she would be the liaison for the region. And so she started working with me on this project and I went down with her, and we spent about a week just exploring and meeting people who live on the salt flats. I felt that if I could find a voice for the landscape, if there were a character, someone who had a tactile relationship with the salt flats, that that might be an interesting voice, a lens through which to tell this bigger story.

And as soon as I met Moisés, it was like, that’s it! He is like a poet. He’s so prophetic. The way that he spoke about his life and about the future was so much bigger than his small life as a salt gatherer. I immediately felt this connection to him. And so I returned two weeks later, very excited. I had some audio equipment – similar to what you have here [a Tascam DR-40 + shotgun mic] – and I was going to record a few hours of interview with him to sort of get the ball rolling and to see how we could start to tell his story. And as soon as I got into the salt flats – almost immediately after – there was a blockade put in place. The local communities were protesting the national government, or something, and were trying to get leverage, so they sealed off the roads, the train lines…you couldn’t get in or out. I was sort of trapped in the Salar with Moisés and his family and some of the other saleros. And it was wild. We just spend all day talking.

HtN: Did you have a camera with you, or just audio?

MP: It was just audio equipment at this point.

HtN: It would have been great to have a camera, as well…

MP: It would have, but I think it worked out, because it was a good introduction. It took a little while for Moisés to get comfortable with the idea of having a camera…a camera is a little more intrusive, in some ways. But voiceover became a main narrative structure.

HtN: So did much of the poetic voiceover that you use in the film come from that time?

MP: Yes. It turned into a week of recording voiceover with Moisés, and a lot of the stuff that is in the final film – including, I believe, the Neil Armstrong story – happened there when we were just trapped in the blockade for a week. And then, I really liked that body of material that we had, even before we’d shot a frame of video, and as I continued to shoot the film over the course of the next five years, at the end of every shooting day – or every other shooting day – we would go into “the cave,” which was like a little tent that I made out of sound blankets, and we would talk for a half hour. It was important to continue the voiceover over the course of that amount of time, because his feelings about his life and about his world, and whether his sons are going to be saleros, it changes drastically.

MP: Yes. It turned into a week of recording voiceover with Moisés, and a lot of the stuff that is in the final film – including, I believe, the Neil Armstrong story – happened there when we were just trapped in the blockade for a week. And then, I really liked that body of material that we had, even before we’d shot a frame of video, and as I continued to shoot the film over the course of the next five years, at the end of every shooting day – or every other shooting day – we would go into “the cave,” which was like a little tent that I made out of sound blankets, and we would talk for a half hour. It was important to continue the voiceover over the course of that amount of time, because his feelings about his life and about his world, and whether his sons are going to be saleros, it changes drastically.

HtN: One of the challenges of making any documentary is figuring out how to develop a close rapport with your subject, so that he or she learns to trust you. That forced proximity with Moisés, in the beginning, turned out to be very fortuitous, then…

MP: It really was. Developing the relationship was really key. But to be honest, Moisés is such a generous guy. Once we knew each other and trusted each other, it didn’t take much. I get asked some time, whether I scripted some the voiceover for Moisés, and none of it is scripted. He’s just that articulate and poetic.

HtN: So I’m sure you met a lot of people down there. At what point did you know that this was the guy? Was he the only one still working the fields?

MP: Well, initially, there were anywhere from 250 to 300 families working out there at any given time, back in 2009, when I went, and so there were a lot of salt gatherers. I met a lot of them. But as soon as I met Moisés, that was it. I don’t know what it is. I can’t really describe it. He was also one of the youngest guys out there, and many of the people that were there were older, and they didn’t really have thoughts about the future in the way that Moisés was thinking about the outside world and his hopes and dreams, and destiny and all this really fascinating emotional stuff.

HtN: He’s a salero/philosopher.

MP: Exactly!

HtN: And it’s like casting a narrative film. You had this range of options and you went for the best guy.

MP: Yeah, as soon as I met him, it was kind of like that. This is the guy.

HtN: So you mentioned how you serendipitously met this photographer who was also a former videographer for Evo Morales. Did you have any problems or restrictions, permit-wise, working in a foreign country, in Bolivia, particularly since one could read the film as being somewhat critical of these policies that are basically destroying the salt fields? On the other hand, in an ideal situation, this mining would benefit Bolivians, although the question to ask is, who will really benefit…no one knows…

MP: I was introduced to Marcelo, who’s the chief engineer of the Bolivian government’s lithium mining operation…

HtN: And he’s a subject of the film…

MP: Yeah, he’s a subject of the film…and it’s an interesting question, because initially, my expectation was that this part of the story was going to be a force that is an adversary to Moisés, that sort of pushes him out and destroys his way of life, and it was going to be that familiar story on the Salar de Uyuni. And as I got to know Marcelo, that turned out to not be the case. It was more complex. As I started to learn more more about Bolivia’s history, there was a lot of gray area. I became sort of torn, and I still am. This clearly could be a very good thing for Bolivia, a country that’s been exploited by foreign powers for centuries. This is the first opportunity they have to use a resource for their own benefit. But the key to it is this pristine, untouched landscape that needs to be mined. And mining is…mining, you know, regardless of who is benefiting. And embracing that complexity was a big moment for the story, where we were no longer going to tell this black and white story of the industrial world vs. the artisanal world.

I was introduced to Marcelo through Jean [Friedman-Rudovsky], who is that photographer’s sister and he was very generous and he gave us a lot of access that no one else got. And he could give us that access because he’s the chief engineer. It took a long time. At first we were only able to shoot certain things, be in certain areas, talk to certain people, but as time went on, he let us tag along on a scene where two of his trucks got stuck in the Salar. That’s obviously not good PR material…

HtN: I like that scene, by the way, because the way you have placed it in the movie, we have already heard Moisés talk about how beautiful the Salar is, and then you have these outsiders coming in to mine the Salar, and they see it in a very different way. In that scene, I think they are cursing this “God-forsaken place.” Different perspectives…

MP: Yeah…

HtN: So I have never traveled to a foreign country as either a documentary filmmaker or a journalist. On a purely bureaucratic level, what is it like making a film in a foreign country?

MP: Normally, just for the logistics of getting your equipment over and registering, for many countries there is a film commission, and you have to fill out a Carnet, which encompasses your passport information and equipment information. It’s all registered and it’s all very official and you get it stamped on the U.S. side. Partly because Bolivia doesn’t have the best official diplomatic relations with the U.S., they don’t do any of that. They have their own system, and you have to work with government officials there, from Conacine. And they check your equipment and talk about what you’re shooting, and it’s a process.

We had a lot of equipment – we shot on a RED camera, and we had a lot more equipment than you would normally have for a documentary – and we had one situation where we were caught up in the airport for 5 hours, where we had to lay the equipment out on the floor and itemize everything…(laughs)…and they had to go through this checklist and check everything off. And there was a FireWire cable that didn’t have a serial number that corresponded to the sheet, and they said that they needed to confiscate this cable…(laughs)…I was just, like, please, take it! Just take it and let us get out of here!

Once you’re in the country, there are a lot of challenges just from shooting in this region, in terms of the climate. I believe that it’s got one of the largest temperature shifts from day to night in the world. It can be very hot during the day – the sun can be very intense – and then at night it’ll be below freezing.

HtN: What’s the elevation?

MP: It’s over 13,000 feet above sea level.

HtN: It’s basically a high desert.

MP: Exactly. It’s in the Altiplano. It’s very high up. It’s exhausting, shooting there.

HtN: And thinner air, too…

MP: Yeah, so you drink coca tea. It affects your metabolism a lot, so I didn’t eat very much, on set. It’s a really extreme environment.

HtN: It’s beautifully photographed. I’m sure all of that equipment helped, but it’s primarily the work of your DP. Could you talk about your Director of Photography?

MP: Our Director of Photography was Andrew David Watson. Forming that relationship was one of the key, core creative relationships for the film. I think that the biggest challenge for us was…I was adamant that I wanted to shoot certain elements in a very deliberate way, and I wanted certain moments to almost feel like a narrative story would unfold. But trying to figure out, and sense, what we can and should control, in terms of the shooting, and what we should just let happen and shoot more vérité, once we found that rhythm, then that was like the machine of the film. Everything locked into place. But yeah, we were using, in certain places, Steadicams, dolly shots, aerial shots…

HtN: Did you shoot on anything other than the RED, or was that your primary camera?

MP: So the film spanned almost every version of the RED camera, over the course of 6 years. When we first started out, the RED camera was this huge dinosaur, and it was really heavy …

HtN: The RED ONE?

MP: The RED ONE! One of the first versions of the RED ONE!

HtN: And then you moved all the way up to, what, the SCARLET?

MP: The SCARLET, and then the EPIC. So the camera got better in quality and much smaller. (laughs)

HtN: But you shot strictly within the RED family?

MP: Most of it is on the RED, for sure. There were some situations where I shot some footage on the [Canon] C300; for example, the aerial footage.

HtN: Was that shot from a drone?

MP: No. That was shot out of a plane. I made friends with a colonel in the Air Force, and we got to the airport at 4 in the morning. It was a four-person plane, and we took the seats out, we took the door off; we were strapped in there with a rock-climbing harness. We needed a smaller camera, because I wanted to set it up on the tripod, to have it be stable, and it just barely fit. So the C300 was compact enough so that could work. That was a fun thing to shoot.

HtN: Well, again, it’s just beautiful. As is the entire film. Congratulations.

MP: I’m really glad you liked it!

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)